A History of Land Art in the American West, Part III

As installation begins at the Texas site for Long Now’s monumental 10,000 Year Clock, it’s worth taking a step back to examine the Clock’s larger artistic context and its place in the history of Land Art in the American West.

Long Now’s staff and many of the individuals working on the project and serving on our board have drawn inspiration for the 10,000 Year Clock, and its placement in the remote landscape of West Texas, from these Land Artists and their great works.

In Part I of our exploration of Land Art in the American West, we covered the birth of the movement in the 01960s and some of the seminal works created by Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt and James Turrell, which expanded the definition of art and opened up new possibilities for the location of artworks. Drawn to the desert for its long vistas, compelling terrain, beautiful light and dark night skies, these artists pushed through the boundaries of art in their day to create monumental works that explored the expansiveness of earth and time.

In Part II of our series, we moved out of the 01960s to explore the work of 3 artists who created their major works during the 01970s and 01980s. We see a shift with these artists to a focus on complete control over the exhibition of their work and meticulous curation of the viewer’s experience coupled with a goal of permanence of the artwork in situ. Marfa, Texas is only about 80 miles from our Clock Site, making Donald Judd’s work there especially relevant to us.

In Part III, we survey the contemporary practice around Land Art, which—though no longer a contained art movement—is still inspired and informed by the work of the early Land Artists. We touch on the activities of the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art + Environment, with exhibits, archives and a major conference; the Land Arts of the American West field program, covering 8,000 miles and multiple sites over 2 months; and the Center for Land Use Interpretation, with their comprehensive database of sites and mobile exhibits. We also explore some of Steve Rowell’s work, which exemplifies some of the new strategies and directions artists have taken to inform and reveal our relationship with the landscape. We close Part III with a list of resources for further exploration of Land Art in the American West.

The Nevada Museum of Art is located in Reno, at the edge of the arid Great Basin. The Truckee River flows by the museum and turns north towards Black Rock Desert, emptying its waters into Pyramid Lake, the remnant of a vast Pleistocene lake. The dusty playas, naked geology and open horizons of the region continue to attract artists who seek to engage with landscape. This setting and the museum’s history help to explain why the museum has become such an important institution for Land Art.

The oldest cultural institution in the state of Nevada, the Nevada Museum of Art was founded in 1931 as the Nevada Art Gallery by Dr. James E. Church, a Professor of German and Classics at the University of Nevada, Reno. Church was the first on record to summit 10,776-foot Mount Rose and build a snow survey station on the mountain, he was intricately connected to the area’s natural resources and an early example of the Museum’s interest in art and environment. — Nevada Museum website

One year after the first Art + Environment Conference in 02008, the museum established the Center for Art + Environment, “an internationally recognized research center that supports the practice, study and awareness of creative interactions between people and their natural, built, and virtual environments.” With the establishment of the Center came a permanent gallery space, a research library and an archive, all dedicated to displaying and encouraging art that engages our environment.

The Center for Art + Environment’s list of exhibitions illustrates how the scope of an area of art — which we can no longer truly call a “Land Art movement” — has transformed and expanded since Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer first roamed the West. Many of the featured artists are directly addressing environmental issues such as climate change and resource scarcity. The Canary Project has photographed locations where scientists are studying the effects of climate change, creating a collection of images and installations entitled “A History of the Future.” In Sierra Nevada: An Adaptation, Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison presented a conceptual map that proposed “a series of long-term ecological responses to recorded temperature increases in the Sierra Nevada.” The map is just the first manifestation of a fifty-year project.

In addition to this explicit environmental activism and scientific collaboration, many of these modern projects have more to do with engaging and re-interpreting landscape and our relationship to it, and less to do with the large-scale earthen sculptures of early Land Art. The Center for Art + Environment’s first Artists|Writers|Environments Grant went to Amy Franceschini and Michael Taussig for This is Not a Trojan Horse, which consisted of a mobile, human-powered horse sculpture that traveled the Italian countryside investigating why working farmers still practice their traditional vocation:

The large-scale, mobile architecture and interactive sculpture collected traces of rural practices: seeds, tools, interviews, recipes and products to enliven the imaginations of farmers and locals through discourse and artistic production. The project was designed as a vehicle for social and material exchange at a pivotal moment in the Abruzzo region, when modes of traditional agricultural production are being challenged by large-scale corporate farming trends as well as new sustainable directions. — Nevada Museum website

The 02011 Art + Environment Conference included presentations by many of the artists behind these exhibitions, as well as photographers, musicians, authors, the director of the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, science fiction writer Bruce Sterling, and The Long Now Foundation’s Executive Director Alexander Rose.

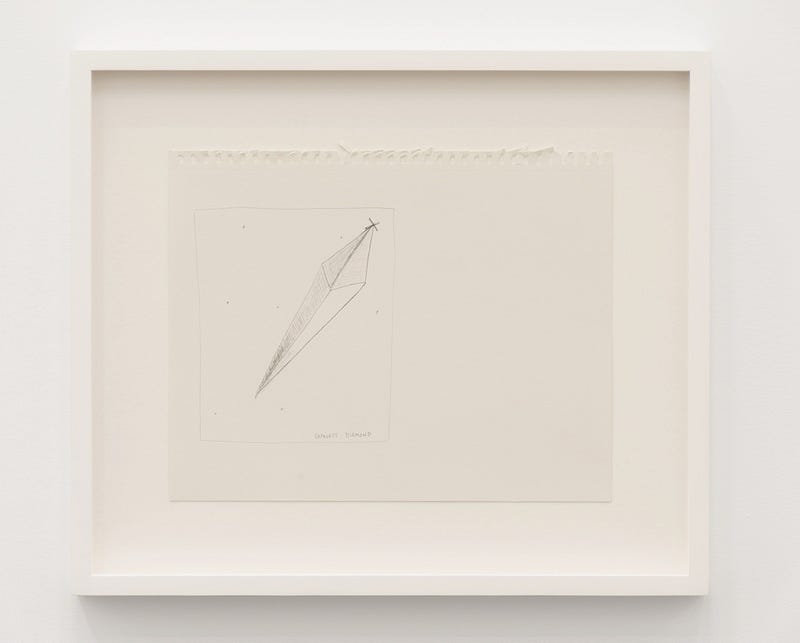

One Art + Environment project aimed to reflect on the terrestrial earth in its entirety. On December 3rd, 02018, Trevor Paglen’s Orbital Reflector launched into low orbit as part of the payload on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. The 100-foot-long diamond shaped mylar balloon was intended to be the world’s first space sculpture. It would be visible to the naked eye, appearing as a slowly-moving star in the sky. Paglen saw the project as a “catalyst” for asking what it means to be on this planet. Unfortunately, due to satellite tracking issues and the U.S. government shutdown, the work of art went unrealized.

In addition to the exhibition space, the Center for Art + Environment’s library and archive are available to the public. The library serves as an art history resource for the community and museum staff, focused on works pertaining to the natural world and the environment. In his introduction to the 02011 Conference’s ‘Field Guide,’ the Center’s Director William Fox wrote specifically about the reason behind their archive:

Why does the Center for Art + Environment collect archives? It has been estimated that up to 97% of the world’s art is destroyed within one hundred years of its making. We’re not familiar with the best classical Greek statues because most of them are destroyed, buried, or underwater. We’ve lost a century of Dutch painting due to war, and countless Asian artworks are gone because of dynastic upheavals and tragic looting. Archive collections offer a momentary stay against decay and loss, but are an important opportunity for researchers to learn from the past — even as the present accelerates away from it. — 02011 A+E Conference Field Guide

The archive includes a collection of materials relating to the early land artists Michael Heizer and Walter De Maria. In fact, one of the Center’s early exhibitions was focused on this collection, indicating the enduring importance and relevance of the artists who created Double Negative and The Lightning Field. One of Heizer’s concepts from the late 01960s came to fruition in 02012 when a 340-ton boulder was placed above a trench in front of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for his piece Levitated Mass. Heizer’s work-in-progress City is also located in Nevada, where it has been under construction since the early 01970s. Long Now board member Paul Saffo recently spotted City during a flight to San Francisco and took the picture, at left, from the airplane.

The archive has also acquired materials from the Land Arts of the American West field program, an educational program in which participants travel through the American West exploring the landscape and the ways in which humans have interacted with it. The Center also supports a number of research fellows, including past Interval speaker Jonathon Keats.

Land Arts of the American West was started by Bill Gilbert at the University of New Mexico in 02000, and since 02002 has also been operated by Chris Taylor, first at the University of Texas at Austin and more recently at Texas Tech University. Each year they pack up the vans and take a group of students on a journey of more than 8,000 miles through the American West, visiting sites that range from canyons and mines to seminal Land Art sculptures and Native American ruins. In the introduction to the book that Taylor and Gilbert published about the program in 02009, they describe the project as “a field program designed to explore the large array of human responses to a specific landscape over an extended period of time.”¹

While the Land Arts program has an indisputably educational function, it is also a work of art in and of itself. Participants engage with the landscape as they travel through it by producing site-specific and ephemeral artwork (in keeping with the program’s no-trace ethic), and follow up with gallery exhibitions once they return from the field. Photographs of many of these works can be seen on the Land Arts website. The practice of displaying artwork that is associated with site-specific land art in an urban gallery is one that began in early Land Art to address the problem of reaching an audience that cannot necessarily visit the actual (often remote) location of a work. Robert Smithson wrote about this duality and defined it as a dialectic of the site and the non-site. Describing an early piece, he writes:

The Non-Site (an indoor earthwork) is a three dimensional logical picture that is abstract, yet it represents an actual site in N.J. (The Pine Barrens Plains). It is by this dimensional metaphor that one site can represent another site which does not resemble it — this is The Non-Site. To understand this language of sites is to appreciate the metaphor between the syntactical construct and the complex of ideas, letting the former function as a three dimensional picture which doesn’t look like a picture. — A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites

The creative aspect of Land Arts is a key component of the program. Chris Taylor writes that “within an expanding definition of landscape, producing work in the field, regardless of scale, is paramount in translating both interpretation and action — in moving from passive awareness to active investment.”² Land Art, he adds, is work that inspires and makes other works.

The notion that Land Arts is itself a work of Land Art meshes well with Taylor’s perspective on the topic, influenced in part by the writings of John Brinckerhoff Jackson. Jackson was a writer and scholar who published Landscape magazine in the 01950s and broadened the scope of geography as a practice.

Jackson’s work, which dominated the first five issues of the magazine, was grounded in what he would later call the vernacular: an interest in the commonplace or everyday landscape, and Jackson expressed an innate confidence in the ability of people of small means to make significant changes, by no means all bad, in their surroundings. — Wikipedia

This all-encompassing interest in the landscape is represented in the yearly itineraries for the program. The group’s 02017 destinations included Cebolla Canyon, Mimbres River, White Sands, Chaco Caynon, Brokeoff Mountains, Cabinetlandia, and Jackpile Mine in New Mexico; Cedar Mesa, Spiral Jetty, Sun TunnelsandCLUI , in Utah; Double Negativein Nevada; the North Rim of the Grand Canyon and the Chiricahua Mountains in Arizona; and Marfa, Texas. Along the way, unintentional works both small and large might be found; even an empty tin can half-buried in the dust beneath a sagebrush is worth investigating and interpreting.

One thing that these sites have in common is their location within the desert landscape of the American West. The pedagogical value of the desert landscape is important for Taylor as a teacher, and Land Artists and miners alike appreciate the accessibility of the land’s geology — embodying deep time in a tangible way. Even works such as Spiral Jetty and Double Negative, constructed in the 01970s, can now illustrate to a visitor the transformative effects of time on an earthen body. In 02007, when Chris Taylor took the Land Arts concept abroad, he went to Chile’s Atacama Desert — one of the driest places on the planet. “Legibility,” he writes, “is the hallmark of arid regions Land Arts works within. Laid bare, these places allow open readings where we can map the intersection of geomorphology and human construction. Arid lands are unable to hold secrets. They challenge our ability to remember and create enduring language.”³

Being present in the landscape is a crucial step to appreciating those qualities. Images of the American West can be impressive, but they are inevitably exclusive, framing a particular part of a view and omitting the rest. Taylor likens standing in the desert to being in an IMAX theater — the experience is immersive in a way that a photograph on a wall cannot replicate.

During the Land Arts’ annual voyage, the group meets with knowledgeable guests who hold seminars on various sites and topics. Among frequent collaborators are William Fox, the aforementioned director of the Center for Art + Environment, and Matt Coolidge of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, who we discuss later in this article. They also visit artisans such as Mary Lewis Garcia of the Acoma Pueblo, who demonstrates traditional pottery making for the students. 02011 brought a new sort of guest, filmmaker Sam Douglas of Big Beard Films. Douglas made a film about the Land Arts of the American West program, Through the Repellent Fence(02017).

Potential expansion of the program includes creating a more focused undergraduate curriculum, the opportunity for postgraduate work and residencies for visiting professionals. There is also a deepening connection to the people they have met and worked with in the field. As Land Arts continues and evolves, both Chris Taylor and Bill Gilbert see the program anchored by their commitment to a hands-on method of inquiry.

With the goal of making perception itself his medium, some of James Turrell’s work immerses viewers in a textureless space. The human mind seeks patterns, visual or otherwise, and when confronted with what appears to be a perfectly smooth surface, attempts to fill the void with something meaningful. In this way, we project and observe something of ourselves onto the artwork; we see ourselves seeing. To some, the desert presents a similar opportunity. Early Land Artists saw a place to take minimalist sculptural practices to extremes, but they also began to think about our relationship to the landscape and how to represent it. In such stark settings, time’s effects, geological forces, and human intervention are all much more apparent than they would be in a busily verdant or urban environment. Seeking to incorporate these effects into their work, Land Artists maintained that viewers had to experience the landscape and the setting in person to truly understand their work.

Much as Turrell’s stark surfaces compel viewers to consider their own agency in perceiving light and objects, the starkness of the desert landscape compels viewers of Land Art to consider the agents shaping the environment. While this relationship isn’t always the primary focus of Land Art, it has become a common theme in the contemporary practice of the genre. Geographers, anthropologists, landscape architects, and others have long evaluated the human/landscape relationship, but usually in a formalized way. Land Artists, on the other hand, take part in what Matt Coolidge calls a non-disciplinary scholarship. Coolidge is among the founders of The Center for Land Use Interpretation, a group of artists and researchers documenting landscape and attempts to interpret it. Or, as they put it:

The Center for Land Use Interpretation is a research and education organization interested in understanding the nature and extent of human interaction with the earth’s surface, and in finding new meanings in the intentional and incidental forms that we individually and collectively create. We believe that the manmade landscape is a cultural inscription, that can be read to better understand who we are, and what we are doing. — The Center for Land Use Interpretation

In its own non-disciplinary way, CLUI is a broad exploration of humanity’s relationship to nature and landscape. They maintain several archives (living, accessible ones you can browse on their website) of interventions on the land, and produce shows and exhibits at their headquarters in Southern California and in mobile exhibition units all over the United States. Their Land Use Database is an extensive index of unique sites, places where land is used in experimental, controversial, secret or otherwise noteworthy ways:

Some sites included in the database are works by government agencies involved in geo-transformative activities, such as the Department of Energy, the Bureau of Reclamation, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Department of Defense. Also included are industrially altered landscapes, such as especially noteworthy mining sites, features of transportation systems, and field test facilities for a variety of high-impact technologies. The database includes museums and displays related to land use, and one of the most thorough listings of land art sites available. — Land Use Database

While one would be hard-pressed to call the Transportation Technology Center of the Colorado plains a work of Land Art (it’s a remote, restricted-access facility with 48 miles of train tracks for crash-testing and studying new train designs, among other things), knowing of its existence offers the opportunity to consider the vast effort our nation has made in order to physically link itself via rail. Beyond just a unique use of land, the TTC has played a role in shaping our use of land all over the continent. The Lightning Field and other pieces of Land Art are documented in the Land Use Database as well and provide similar opportunities for considering our use of the planet’s surface.

In addition to the Land Use Database, CLUI maintains the Morgan Cowles Archive:

The Morgan Cowles Archive is the principal collection of images at the Center for Land Use Interpretation, as well as the initiative to preserve and present them to the public. The archive draws from over 100,000 images of thousands of places taken by people working for the CLUI since the inception of the organization in 1994.

The Center’s American Land Museum is a nation-wide, distributed network of exhibition sites:

The physical form of the individual museum locations will differ according to site considerations and available development resources. The primary “exhibit” at each location is, naturally, the immediate landscape of the location itself. Collectively the individual exhibit sites comprise the American Land Museum, a museum both situated in and made up of the landscapes of America.

Though its description might seem a bit cryptic, the American Land Museum is a project that is meant to encourage actively seeing one’s surrounding landscape. Like many projects by CLUI, it seeks to present places without judgment in order to encourage viewers to form their own opinions about places and their relationship to them. The Center catalogues and exhibits artistic and utilitarian interventions on the landscape with the faux-formality of a very serious, clinical institution. CLUI’s belief is that by cultivating a bit of ambiguity and disorientation in this way, they can encourage viewers to actively orient themselves to the landscape.

Many years ago, on a visit to the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, artist Steve Rowell noticed a nondescript office nearby and, intrigued by its sign, wandered in. He found himself in the headquarters of the Center for Land Use Interpretation and felt an immediate resonance with the Center’s vision. Several years later and newly a Californian, he started using the resources offered by the Center to help him familiarize himself with his new surroundings. He kept in touch, going on some of the tours they offer, and was hired in 02001 to help redesign their website.

While working with the Center, Rowell traveled with one of its founders, Matt Coolidge, to a site north of Ely, Nevada where NASA used to conduct monitoring of a research program focused on hypersonic flight. Some of the craft that were tracked by the station had flown to the very edges of space and Rowell found the age and distant reach of the location an inspiration. Much of the artwork Rowell has done since then, with CLUI and otherwise, has focused on themes represented by that site: the technological expressions of power, desolate landscapes, extreme distances and isolation, and ground-based support for activities in the air.

Steve Rowell doesn’t consider his work to be Land Art, but he has been inspired by the form and many of the questions it poses and has overlapped geographically with many of the artists and sites we’ve previously discussed.

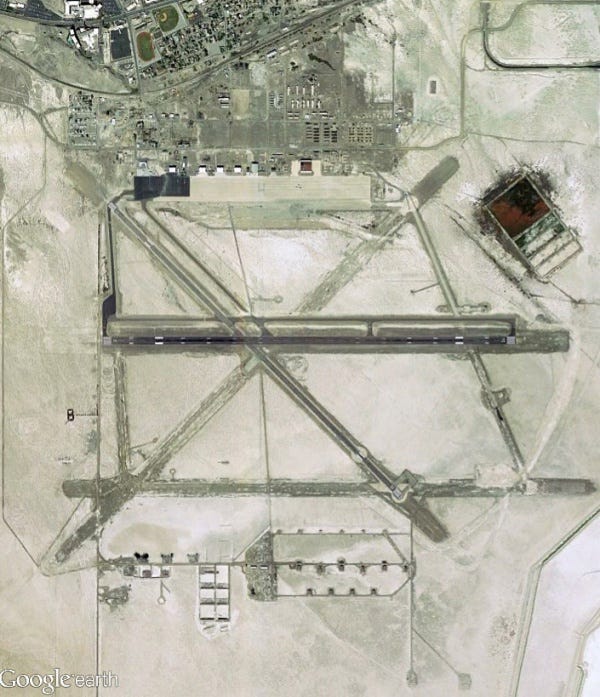

In 02008 he created a piece in Marfa with Simparch called TX AUX IN, which featured field recordings from desert-based military listening stations, aircraft testing facilities and radar stations. The recordings are played for a listener inside an old camper trailer that’s been converted to keep a maximum of light and sound out, creating an immersive audio experience. He’s also a Research Director with Office of Experiments, who state:

Our aim is to develop autonomous resources such as archives, databases, publications and field guides, through which we can draw material evidence and interpretive speculation on the fabric of sites, spaces and events. In doing so, we hope to open and create alternative public resources that will inform the broader imaginary, perception, engagement and critical response to the scale, time base and structures of the rational world. — Office of Experiments

Long Now worked closely with Steve Rowell around the opportunity to visit the Svalbard Seed Vault; that visit led both to new audio and visual pieces by Rowell and added to Long Now’s growing collection of information on underground construction around the world.

Rowell’s work is a good example of what Chris Taylor has described as Land Art’s proclivity to generate other works. Interventions on the landscape aren’t always made with aesthetic or artistic intentions, but from Spiral Jetty to the Wendover Airfield, from the Mojave to the Arctic, humanity’s marks on the planet are open to a wide array of interpretations which can continue to inform and reveal our relationship with the landscape. Land Art helped to diffuse discussions of that relationship beyond strict disciplinary boundaries and Steve Rowell’s work (along with that of CLUI and others) further expands the frame by also drawing inspiration from these non-artistic works.

One can trace a direct line from the early large scale Land Art pieces and artists of the 1960s, through the refinement of the experience of the art as exemplified by Judd, De Maria and others in the 1970s and 80s to the multi-faceted approaches to art in the landscape today. These earlier works and explorations—many of them still visible or being worked on today—continue to inform and inspire not only the practice of the new generation of landscape artists, but how Long Now creates the experience of visiting the 10,000 Year Clock in the mountain.

Written by Austin Brown, Danielle Engelman, and Alex Mensing. Edited and updated by Ahmed Kabil.

We would like to extend many thanks to Chris Taylor of the Land Arts of the American West program, Matt Coolidge of The Center for Land Use Interpretation, and artist Steve Rowell for sharing their knowledge and perspectives with us over the course of several telephone interviews.

Footnotes:

[1] Taylor, Chris and Bill Gilbert, Land Arts of the American West, University of Texas Press, Austin: 02009, pp. 25.

[2] Taylor, Chris et. al. Incubo Atacama Lab. Incubo, Santiago, Chile: 02008, pp. 11.

[3] Ibid., pp. 11.

Works Cited:

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation

- Land Arts of the American West

- Nevada Museum of Art

- The Office Of Experiments

- Prime, Richard. “See! Colour!” Cool Hunting: 02011.

- Simparch

- Smithson, Robert. “A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites.”

- Taylor, Chris et. al. Incubo Atacama Lab. Incubo, Santiago, Chile: 02008.

- Taylor, Chris and Bill Gilbert, Land Arts of the American West, University of Texas Press, Austin: 02009.

Additional Resources:

- The Center for Land Use Interpretation publishes an annual newsletter. Back issues of the newsletter are free online and print issues are available via subscription through the CLUI store, which also has a list of recommended books.

- Steve Rowell on Twitter: @fieldtone

- Nevada Museum of Art on Twitter: @nevadaart

- Texas Tech’s Land Arts of the American West program on Twitter: @TTUCoA

- J. B. Jackson. American Space: The Centennial Years, 1865–1876 (1972)

- The ecoartspace blog is a wide-ranging resource of current news and links.

Interesting artists and projects that fell outside the framework of this article include:

- William Lamson, A Line Describing the Sun

- Lita Albuquerque, Stellar Axis, The Spine of the Earth

- Earthbound Moon

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe