Wilson Seminar Primer

“The Social Conquest of Earth”

Presented by The Long Now Foundation and the Exploratorium

Friday April 20, 02012 at the Palace of Fine Arts Theater, San Francisco

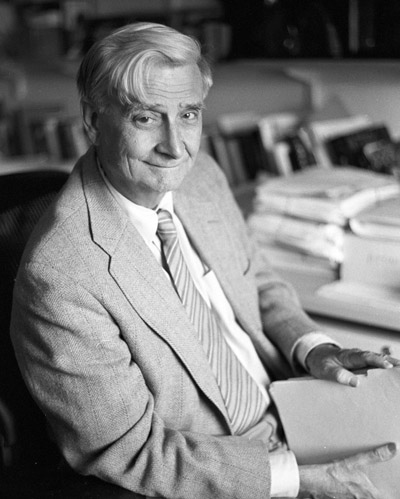

Edward O. Wilson started small. As a young man interested in biology, the lowly ant was his passion. Ubiquitous, diverse, and socially complex, however, ants provided Wilson with data and inspiration that would eventually grow into sweeping theories of evolution, behavior and culture. Those theories have been both fiercely defended as foundational scientific dogma and vehemently rejected as dangerous heresy – against each other in some cases.

One of the larger questions Wilson’s work with ants would eventually address was how to reconcile altruism with selection of the fittest. Why do we observe animals sacrificing their own procreational success for others? Darwin himself proposed an answer – that there is an adaptive advantage in assisting those, such as siblings, who are closely related to ourselves. But it wasn’t until the 20th century that Kin Selection, due partially to Wilson’s work, become the textbook answer.

Wilson’s belief that aspects of social behavior could be explained with evolutionary logic led to his 1975 book called Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. That the deep past of an organism’s evolution could shape behaviors in the present wasn’t a brand new idea, but seeking to explore it in depth, Wilson included the highly social homo sapiens in the book’s last chapter. Humanity’s cooperation and empathy was understood by many at the time as a cultural invention that worked in spite of the selfish nature implied by the “survival of the fittest.” Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal would later call this Veneer Theory. But as Kin Selection and sociobiology were beginning to illustrate, altruism could be observed in the animal world and could be traced to a much deeper origin: biological evolution. While this might seem like a good thing – that humans won’t automatically revert to savagery in the absence of modern culture – it set off alarm bells to those who heard it to mean that human behavior is determined by biology.

Wilson would later describe the broader goal of Sociobiology’s last chapter in a book called Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Rather than ever implying that human behavior is entirely programmed by DNA, Wilson sought to establish a framework for beginning to unite the findings of the humanities and the social sciences with those of evolutionary biology and the natural sciences. In Consilience he explained that human culture isn’t determined by DNA, but that in some ways it is constrained by it. With that in mind, he advocated for interdisciplinary research that would begin to identify what influence DNA has on behavior, and what other influences must be taken into account.

Spanning the better part of half a century, Wilson’s career has been a long and a fruitful one. But Wilson isn’t interested in taking any of it for granted. He has, in fact, very recently mounted one of the most significant attacks on Kin Selection since he helped put it on the map in the first place. By focusing on eusocial species such as ants, bees and humans, Wilson is proposing that Group Selection, a less popular and long ignored theory, better describes the cooperation we see in ourselves and the animal kingdom.

Spanning the better part of half a century, Wilson’s career has been a long and a fruitful one. But Wilson isn’t interested in taking any of it for granted. He has, in fact, very recently mounted one of the most significant attacks on Kin Selection since he helped put it on the map in the first place. By focusing on eusocial species such as ants, bees and humans, Wilson is proposing that Group Selection, a less popular and long ignored theory, better describes the cooperation we see in ourselves and the animal kingdom.

His most recent book, The Social Conquest of Earth, explains why he’s changed his mind and what this new paradigm means for our understanding of human nature. He’ll discuss these findings on Friday April 20th at the Palace of Fine Arts Theater. This event is sold out, but you can sign up for the podcast on the Seminar page, where we’ll also post video of the talk afterwards.

Subscribe to the Seminars About Long-term Thinking podcast for more thought-provoking programs.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe