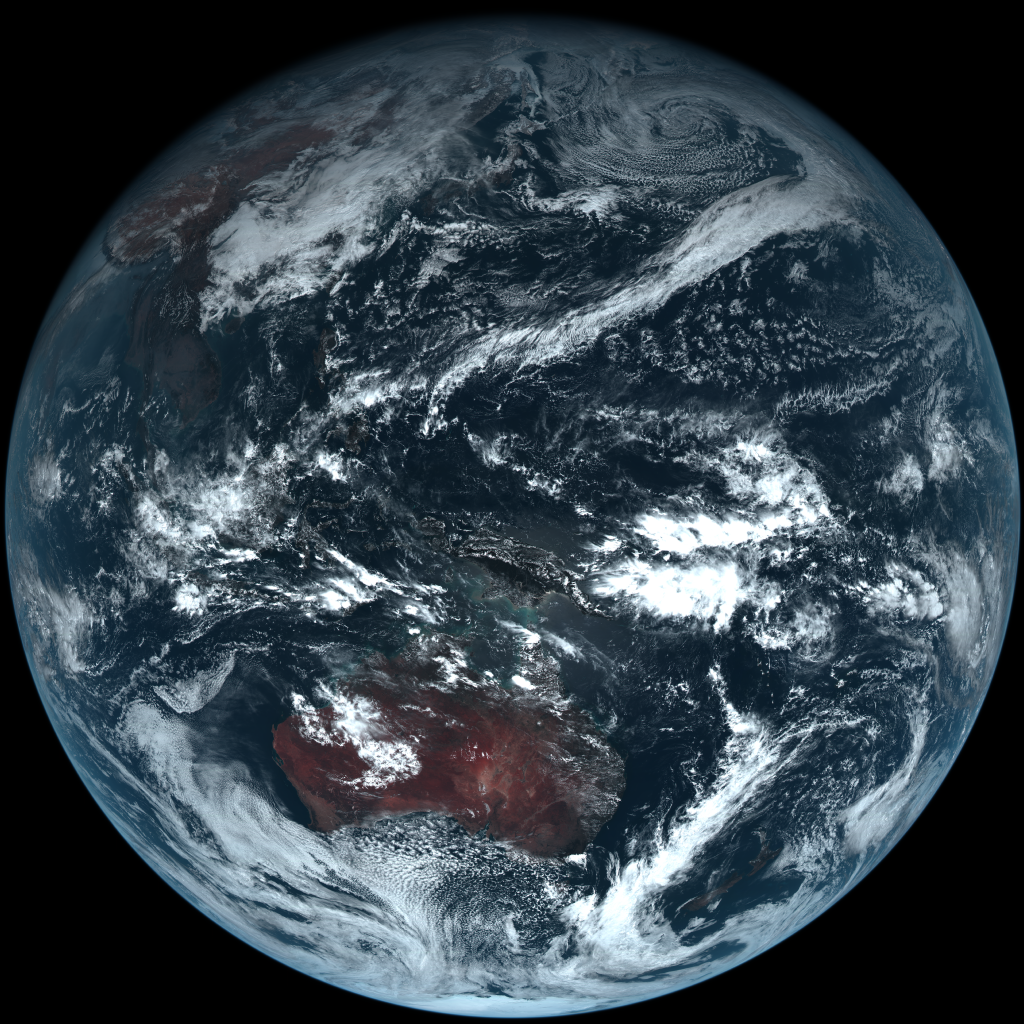

Himawari-8 Satellite Offers A New Look at Our Planet - 144 Times Per Day

A sense of perspective is unavoidable from 22,000 miles out. Looking down at Earth from that distance — almost three times farther than the diameter of the planet itself — allows a view of the globe as a massive organic system, pulsing with continuous movement. (NY Times)

Last month, Japan’s new Himawari-8 weather satellite began sending data back to Earth. Launched in late 02014 to help track storm systems and other weather patterns in the Pacific Rim, it looks down on Earth from a geostationary orbit, at about 36,000 kilometers (or 22,000 miles) from the surface.

Its considerable distance from Earth isn’t necessarily surprising; most weather satellites do their work in high earth orbit. But what makes Himawari-8 unique among its colleagues is the fact that it is capable of taking full-color photos of the entire planet. Every day, it sends 144 of these “living portraits” back down to Earth – or one photograph every ten minutes.

With an unprecedentedly high resolution that can visualize features as small as 500 square meters, these images will help scientists better understand the genesis, evolution, and outcome of large-scale weather patterns. But on a broader level, the pictures Himawari-8 sends back can’t help but awaken in us what the Planetary Collective has called the Overview Effect: the combined sense of awe and oneness that seems to come over us all when we see images of the whole Earth, framed by the blackness of space.

The data Himawari-8 produces is meant to help us better grasp the ever-changing, fleeting, and highly localized behavior of the Pacific atmosphere. But it also offers us a reminder to step outside of ourselves and consider the fact that we ultimately inhabit a very small corner of a much larger unit of space and time.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe