It’s Good to Be Infrastructure

Using Stewart Brand’s Pace Layers framework to think about platforms, power, and long-term investing

Editor's Note: Dave Bujnowski, an investment manager at Baillie Gifford, wrote this essay on applying the Pace Layers framework to investing in 02019. It is just as prescient today. At the end of the essay you'll find an addendum, written in 02026, reflecting on the Pace Layers framework seven years on.

In 02000, Long Now cofounder Stewart Brand wrote The Clock of the Long Now, a book whose messages and insights are so profound that trying to boil its essence down to a few words seems like sacrilege. But I’ll try. To use Brand’s own words, the book is about time, responsibility and how civilizations that think about the long-term tend to be healthier and, put simply, “better at looking after things.” With the book, Brand effectively offers a sermon that poses the all-important question: how can we make long-term thinking automatic and common instead of difficult and rare?

If you are an investor — or, indeed, a human — who thinks in decades as opposed to quarters, the book will likely strike a chord. That said, my goal here is not to elaborate on Brand’s view on time and humanity (as virtuous as it is), nor is it to weigh in on his thinking about responsibility or the evils of short-termism (as spot-on as that seems). Rather, it is to draw from a surprisingly useful framework that he introduces in the book by applying it to investing and business analysis. Specifically, I’m going to show how his pace-layering model can be used to identify businesses that are in the midst of:

- Expanding their market opportunity

- Widening their moat, and

- Gaining power in a world rife with disruption and business-model wars

For long-term investors, building conviction around these three attributes is about as good as it gets. So, let’s dive in.

Introduction: Stewart Brand’s Pace-Layering Model

An important clarification up front: there is precisely zero mention of investing or business analysis in The Clock of the Long Now. Stewart Brand was focused on helping civilization, not on analyzing businesses or business models. And while I’ve never met the man, I’d also be willing to bet that Brand had precisely zero intention for this specific pace-layering model to be used as a tool for investors. But that’s exactly what we’re doing here.

At its core, the pace-layering model is about how systems work and how the different entities that make up the system interact. While Brand applies it to the health of one system (civilization), it’s also very relevant to others, like the economy and the businesses that make it up.

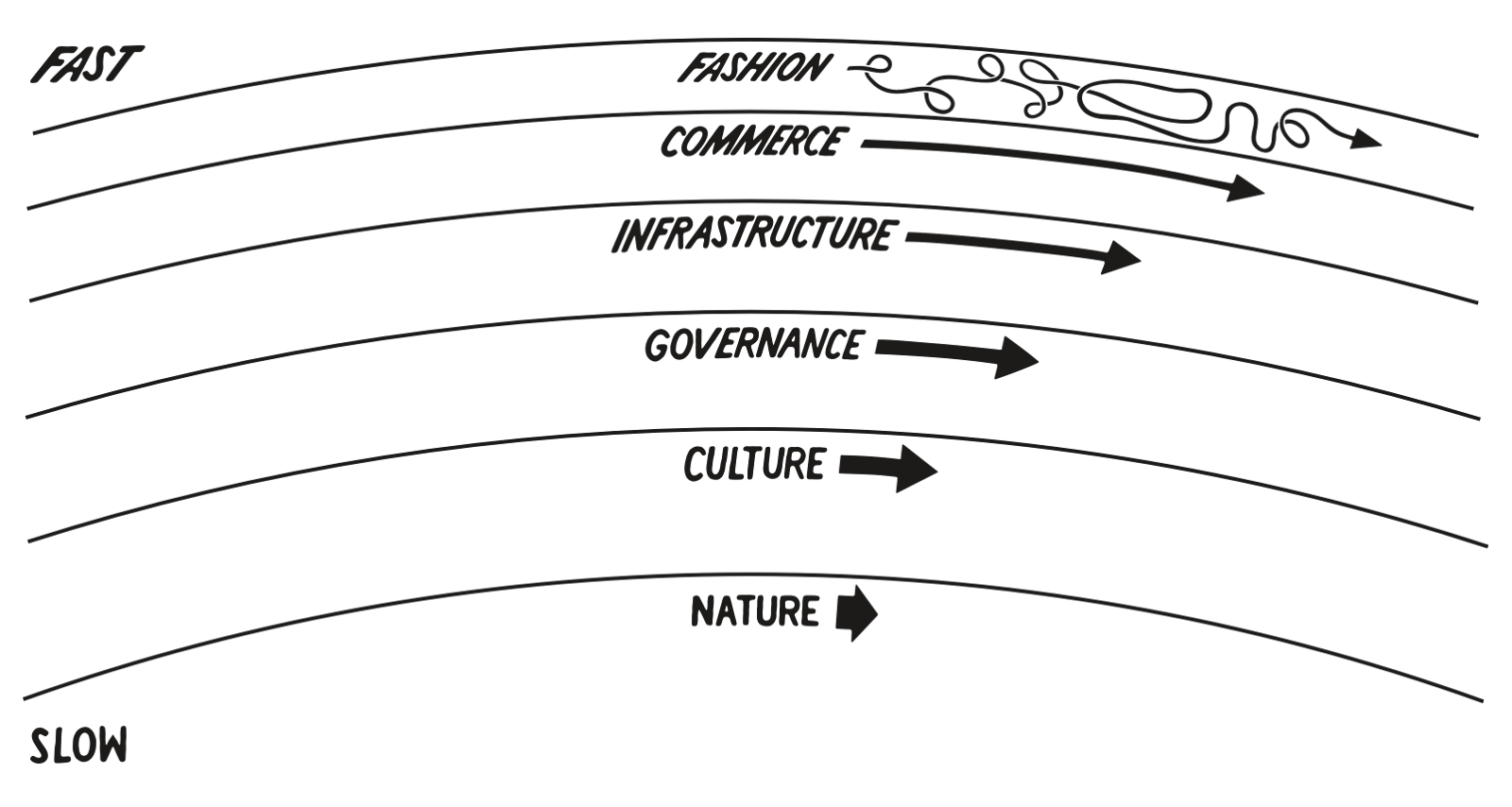

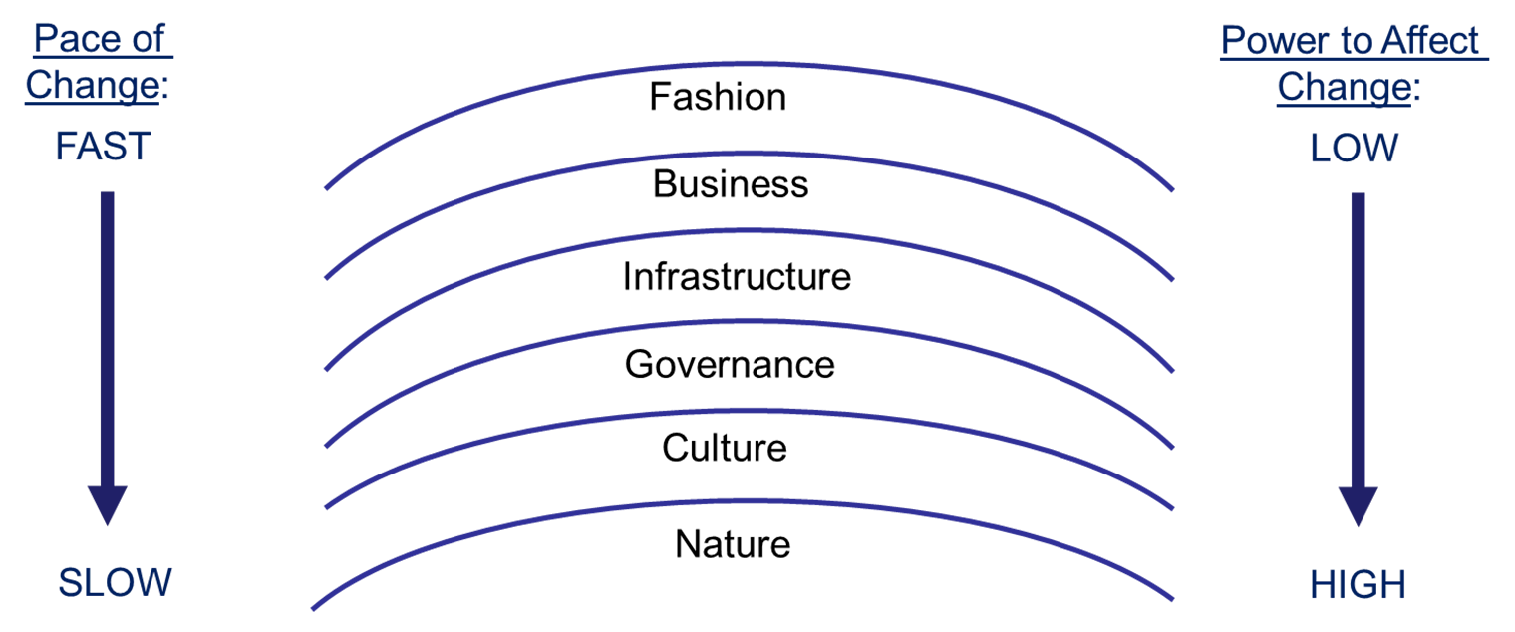

Brand suggests that different “layers” of society change at different pace. From most rapidly changing to slowest moving, the layers are: Fashion, Commerce, Infrastructure, Governance, Culture, Nature.

Digging a little deeper, Brand asserts that:

- The combination of the fast and the slow layers gives the whole system (civilization, that is) its resilience. Together, they help create a strong but flexible structure.

- There is a relationship between the layers, and they need to respect each other’s pace to create a healthy system.

- Society tends to focus its attention on the fast-moving layers, but the slow-moving ones have all the power. They tend to control and constrain the fast-moving layers.

- Meanwhile, the fast-moving layers inform and instruct the slow-moving ones with innovation and — occasionally — revolutions.

Again, Brand’s primary goal is to apply this model to effect long-term change in civilization at large. For instance, he suggests that if you want to do lasting good in the world, it’s best to focus your efforts on the slow-moving layers. Changing those would affect a lot more than influencing a top layer.

So, what resonates with me, and why would I want to apply this to investing?

Two things stand out most:

- I see a relationship between (a) the pace of change and (b) the likelihood of a company being disrupted, which could potentially inform us about its competitive edge. As in: when change is rapid, a business is potentially more likely to be disrupted — all else equal.

- The words control, constrain, and power also catch my eye. In studying how much value is unlocked (or destroyed) when business models collide, and new victors emerge, the notion of where power resides in a system seems incredibly relevant, doesn’t it? This model speaks to that.

With that, let’s see how the model can apply to real life situations.

Six Practical Applications of the Pace-Layering Model

Application #1: The Virtues of Participating in the Lower Layers

An important acknowledgement: I was introduced to the pace-layering model through my former mentor and business partner Pip Coburn, and for the last 15 years we collaborated to find insights buried within. So, to the extent this model can generate insights — and returns for our clients — much credit goes to Pip.

Our core thought involved the idea that if a company can build its business — and achieve success — at a layer that changes less frequently (like Infrastructure), there is a case to make that it has a stronger and more lasting business model than it would have if it relied on participating in a more fast-moving layer (like Fashion).

To be clear, this doesn’t necessarily make it a better or worse business overall, but it does directly affect how susceptible the business may be to the whims and wants of society and, correspondingly, the visibility we might have as investors into its cash flows.

The first time we applied this thinking was back in 02003, when Apple was achieving early success with the iPod. At the time, you may recall, Apple was in the early stages of a turnaround. The iPod was in its second year of existence, and it was hot.

The bear case on Wall Street was that Apple was a “retail” company that was depending on hit product cycles (the iPod), and if they missed a product cycle, they were toast. While this seems far-fetched 15 years (and hundreds of billions of dollars in market cap) later, it was a real conversation back when Apple’s annual revenues were just $6 billion per year.

At the time, we were long Apple in the portfolio and, while the “retail/product cycle” thinking made decent sense, Pip and I had an inkling that there was something bigger going on.

After a couple months of sitting with the question, we had our first “a-ha Stewart Brand” moment. Pip and I determined that there was indeed something more lasting about Apple’s success. Its edge didn’t just have to do with its product, or its user interface, or its brand, or the Steve Jobs halo effect (each of which was powerful in its own right). Rather we thought it was because with iTunes, Apple had effectively made the move from Fashion to Infrastructure in Stewart Brand’s model. And the pace of change at that layer was slower and came with entirely different competitive dynamics than if Apple stayed at the Fashion layer.

In other words, as we “burned” our compact discs (CDs) into the iTunes system, it became infrastructure. And to switch the music out of that infrastructure was something few users would want to deal with, even if Samsung or Texas Instruments came out with a new MP3 player that really caught our eye or happened to be priced less expensively.

Part of the magic here was that because iTunes generated extremely little revenue, it was therefore overlooked by Wall Street. Yet it was the strategic element that provided a deeper and more lasting competitive advantage. It also served as a fundamental building block for our Apple long thesis for the next decade.

Application #2: Power, Control & Constraint

Our Apple example demonstrated how becoming Infrastructure can potentially help a business protect itself from disruption. But when the notion of power and/or leverage is considered, the idea of a company participating at lower levels of the pace-layering model becomes even more exciting.

The basic idea is that the lower layers of the model control and constrain the opportunity set of the layers above them. Here, Stewart Brand cites the work of Robert O’Neill’s A Hierarchical Concept of Ecosystems and highlighted this particular insight: “The dynamics of the system will be dominated by the slow components, with the rapid components simply following along [...] slow constrains quick; slow controls quick.”

It makes sense. For instance, regulators (i.e., the Governance layer) have the power to constrain what Infrastructure looks like, which, in turn, would influence what business (i.e., Commerce) would even be possible.

There are some wonderful real-life examples:

- Perceived global warming (Nature) is slowly affecting Culture, which is in turn conditioning Culture and regulation (Governance) in many parts of the world.

- In 02010, China (Governance) effectively kicked Google (Infrastructure / Commerce) out of the country.

- Advertising (Commerce) can control what does or doesn’t become a fad (Fashion).

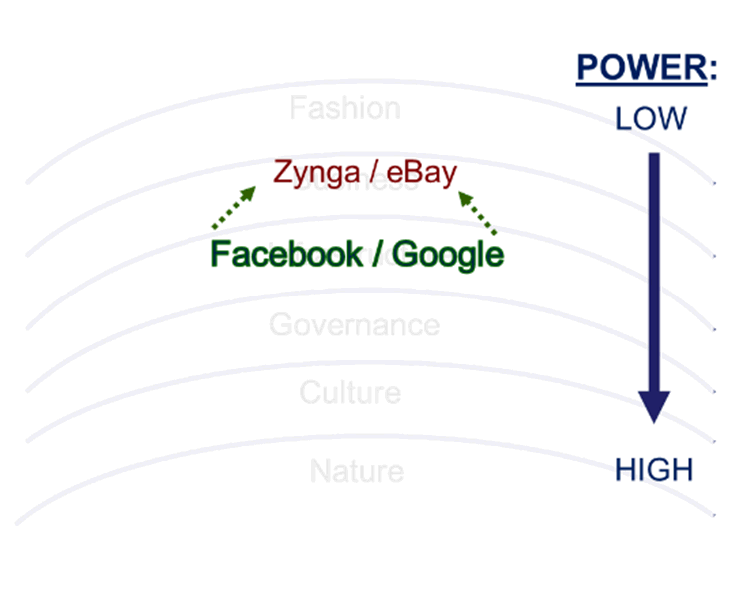

When it comes to investing, this particular element of the model — control, power — is perhaps the most prevalent today, given how many business models are colliding. One example that shines a light on the dynamic brilliantly involved Facebook and game developer Zynga circa 02010.

Remember FarmVille? It was a game developed by Zynga in 02009 that became wildly popular on Facebook, reaching over 80 million players just six months after launch. This was around the same time that Facebook hit the serious part of its growth curve. (In early 02009, it had 150 million users. By the end of 02009, it was over 350 million.)

The point: both Facebook and Zynga were on fire. But at the time there was a serious discussion taking place on Wall Street about whether Farmville was driving Facebook’s business or Facebook was driving Zynga’s business.

Again, it seems obvious in retrospect, but this was a real debate.

To be sure, the relationship between Facebook and Zynga was mutually beneficial, but to answer the question “Which company has a more powerful, durable business model?”, Stewart Brand’s model offered intensely powerful insights:

- Facebook is the infrastructure.

- FarmVille is Fashion/Commerce.

- Infrastructure controls Fashion/Commerce.

And in early 02012, as if straight out of Stewart Brand’s playbook, Facebook tweaked the algorithm which determined what games were “pushed” to its users via News Feed, and FarmVille was crushed.

For what it’s worth, eBay had a similar high-profile problem with Google redirecting traffic years later. And as the major platforms gain power, this is a dynamic that is increasingly prevalent.

The point: it’s good to be Infrastructure.

OK, So …What Is “Infrastructure” and How Can I Become It Too?

A key assumption we’re working with here is that, all else equal, it is better for a business to be participating at a lower/slower level in this model than a higher/faster one. This raises the question: how do we define infrastructure, and how does a business become infrastructure?

Merriam-Webster offers a few definitions of infrastructure. One involves the “underlying foundation of a system or organization.” Another is “the resources required for an activity.” I like the idea that infrastructure can be both a true foundation that is underneath a system as well as a resource.

My own working definition combines the two: something that is required for the healthy operation of a system.

Said another way: to be a fad, you must be liked. To be infrastructure, you must be required. And the more entities that need you, the deeper you have driven into infrastructure. You have gained power. Leverage.

Practically speaking, there are several types of infrastructure:

- It could be physical, which I view as the most classic definition of the word. Examples include the roads or electricity grids upon which our society rests.

- Or it could be habitual. Example: coffee has become an absolute requirement to start my day. It’s a softer version of infrastructure, but it still fits.

- Or, it could simply reflect how important an entity has become to the system it participates in, even if it doesn’t “sit underneath” anything else like our first example. For instance, if a brand represents a very large portion of a retailer’s sales, it could represent infrastructure in that particular market. If Nike pulled its products from, say, Foot Locker’s shelves (where it represented nearly 70% of sales in 02017), Foot Locker would be hurt.

Broadly speaking, a useful litmus test for whether an entity has become infrastructure has to do with power and whether other entities rely on it as a foundation or a resource that significantly influences their own well-being.

With that behind us, let’s look at some other applications of the model.

Application #3: Slower Layers Must Be Agile & Adaptive

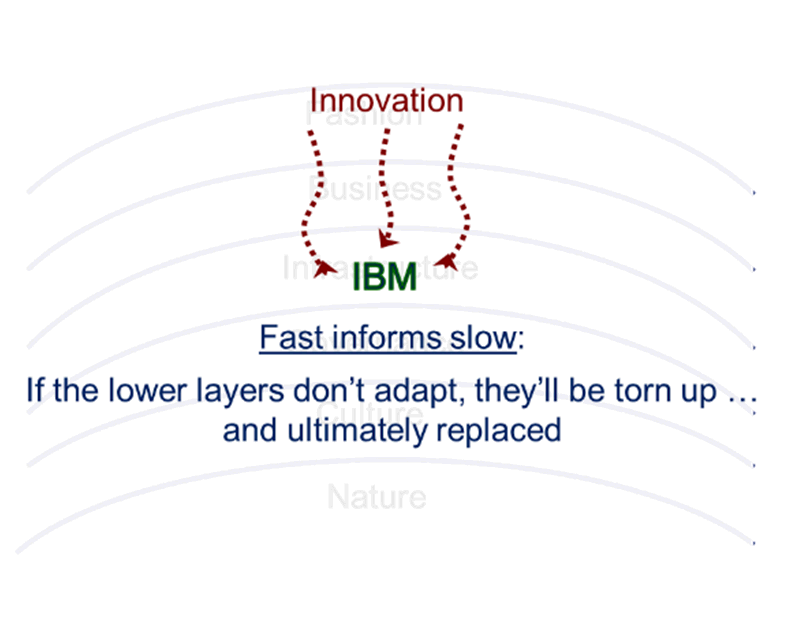

While the slower layers might have all the control, the rapidly changing layers aren’t completely powerless. Says Brand: “Influence does percolate in the other direction. The slower [layers] gradually integrate trends of rapid change within them [...] the fast parts instruct the slow with innovations and occasional revolutions.”

In another book, How Buildings Learn, Brand goes on: “Design of a system is important to consider. A design imperative emerges: An adaptive building has to allow slippage between the differently-paced layers […] Otherwise, the slow systems block the flow of the quick ones, and the quick ones tear up the slow ones with their constant change.”

The point: the slow-moving layers (like Infrastructure) have to be adaptive. Otherwise, they’ll be “torn up” by the innovation and change that is taking place in the faster layers.

Examples?

Here, I think of IBM over the past decade.

When it came to how IT has traditionally been distributed and consumed, IBM had a multi-decade run as the infrastructure company. Businesses were literally built upon their servers and mainframes, which were recommended and installed by IBM’s army of consultants and systems integrators.

Meanwhile, this thing called “cloud computing” was emerging. It represents the “innovation” and “occasional revolution” that Stewart Brand speaks of – the very ones that those in the slower layers have to (a) be aware of and (b) adapt to.

For its part, IBM did neither. What it did do was respond to the changing world by, regrettably, focusing on financial engineering tactics as opposed to a real strategy that might help IBM adapt: in 02006, Sam Palmisano famously guaranteed Earnings Per Share (EPS) going from $6 to $10 by 02010. Yes, he accomplished this through share buybacks, but the earth was beginning to shift underneath IBM’s feet.

Application #4: TAM Expansion for “Infrastructure” Companies

Earlier, in my introduction, I mentioned that this model not only helped us identify companies whose moats were widening, but also those who were in the midst of experiencing a dynamically expanding total addressable market (TAM).

What we’re getting at here is this: a business that represents a lower layer in the model (e.g., Infrastructure) controls the opportunities that sit above it (e.g., Commerce). It then stands to reason that — again, all else equal — if that business had the wherewithal and resources to do so, perhaps it could create the very Commerce that sits atop its Infrastructure.

Of course, sometimes Infrastructure is regulated and these types of greenfield Commerce opportunities are outlawed. But not always.

Take Amazon Web Services (AWS), for example. It is quite literally the (physical) infrastructure upon which more and more IT is being used and delivered. Not only is that a powerful position in its own right, but as an added benefit, AWS is constantly adding services beyond mere compute and storage, moving up the stack and selling software like databases.

This is Commerce, and it was previously not a part of its addressable market.

Self-directed, ready-made TAM expansion. Brilliant.

Application #5: Best of Both Worlds? The Open-Platform Business Model

So far, we’ve described a few situations that led to anything but a “healthy” system. In one case, a slow-moving, powerful layer exercised its control to harm a business that sat on top of it (Facebook/Zynga). In another case, a slow-moving layer was harmed because it didn’t “listen to” the change that was taking place around it (IBM).

It seems to us that the best place to build a business — again, all else equal — would be on a slow-moving layer (e.g., Infrastructure) which lends itself to longevity, but with agility effectively “built-in” such that there would be very little friction between it and the fast-moving Fashion layer on top of it.

Sounds a lot like the open internet platforms, doesn’t it?

I consider the major platforms of the day (e.g., Tencent, Facebook, Google, Apple, Amazon) to be Infrastructure. But by being open to third-party stakeholders (e.g., app developers, game developers, advertisers, individual content creators), these platforms can adapt in sync with the rapidly changing fads far more easily than Infrastructure companies of yesteryear. More than any other business models we can think of, they are uniquely geared toward both endurance and agility.

It's a powerful combination.

Of course, this doesn’t mean these platforms will last forever — which is exactly what the pace-layering model helps us explore next.

Application #6: Too Big to Fail? Hardly. Existential Threats to Platform Companies

Our assertion here is that the major platform companies — Amazon, Google, Facebook, Tencent, Alibaba— have become infrastructure in society (and the economy). But while the Infrastructure layer of society represents a fantastic place to run a business, it’s not a panacea. There are still layers underneath Infrastructure in Brand’s model that are more powerful: Governance, Culture and Nature, which, by definition, can make life more difficult and sap some energy out of the monster platforms if they choose.

So, questions to consider:

- Will entities in the Governance layer bristle at the power the major Internet companies are amassing? If so, will they exert their power to push back?

- Going deeper into Brand’s stack, a societal layer that is even more powerful than Infrastructure and even more powerful than Governance is Culture. Might the “bias against big” — a force that seems to be growing increasingly powerful in society — eventually lead people to revolt against these monster platforms? Will there be a cultural backlash?

Addendum (02026): Pace-Layering, Seven Years On

The last seven years have been a live test of Brand’s core claim that systems are “strong but flexible” precisely because different layers move at different speeds — and that the slower layers ultimately constrain the faster ones.

COVID-19 was a Nature shock that rapidly rewired Culture (how we work, learn, and socialize) and forced Governance and Infrastructure to respond at speed. It compressed years of digitization into months once the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic in March 02020.

Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 02022 reminded investors that geopolitics (Governance) sits below Commerce in the stack, re-pricing energy security, supply chains, and defense capacity in a way no product cycle ever could.

At the same time, climate and resiliency moved from “values” to “constraints,” with policy responding accordingly. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (August 02022) accelerated capital formation around electrification and clean energy.

Within the Commerce and Infrastructure layers, the “power/control” dynamics became even clearer. Digital infrastructure kept absorbing more of the economy (cloud, identity, payments, logistics, and cybersecurity), and then generative AI arrived as a fresh “fast-layer” discontinuity, punctuated by ChatGPT’s public release in November 02022.

Simultaneously, these technologies deepened the strategic importance of the “slow” substrate: data, semiconductors, and compute capacity. Yet the same period also sharpened the counterforce we flagged in the original paper: platforms meeting Governance and Culture.

The EU rolled out the Digital Markets Act, Digital Services Act, and AI Act. The U.S. stepped up antitrust remedies and export controls that explicitly target advanced computing supply chains. The point has been consistent: when Infrastructure becomes systemically important, Governance reasserts itself, and the investable surface shifts toward compliant, trusted, and strategically aligned Infrastructure.

The practical takeaway: pace-layering remained relevant and became more investable. It helped explain why the market’s biggest winners increasingly cluster around enabling Infrastructure — cloud, chips, and AI tooling — real-world resiliency buildouts, energy transition, industrial automation, defense, and security: domains where slow layers are finally forcing change.

It also helped clarify the risk: “fast” innovation can create extraordinary new Commerce, but durability still accrues to businesses that either are Infrastructure or can adapt as Governance and Culture tighten the rules of the game.

Brand’s hope was making long-term thinking more “automatic and common.” That maps neatly onto today’s investment trend: funding the foundations — digital, physical, and institutional — that let societies keep functioning and improving under stress.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe