Seeing the Whole Earth From Space Changed Everything

Now, a new project is zooming in closer to inspire awe and a sense of responsibility

"Once a photograph of the Earth, taken from outside, is available…a new idea as powerful as any in history will be let loose."

- Astronomer Fred Hoyle, 01948

I. “Why Do You Look In A Mirror?”

In February 01966, Stewart Brand, a month removed from launching a multimedia psychedelic festival that inaugurated the hippie counterculture, sat on the roof of his apartment in San Francisco’s North Beach, doing what he usually did when he was bored and uncertain. He took some LSD and got to scheming.

“There I sat,” Brand later recalled, “wrapped in a blanket in the chill afternoon sun, trembling with cold and inchoate emotion, gazing at the San Francisco skyline, waiting for my vision. The buildings were not parallel — because the Earth curved under them, and me, and all of us; it closed on itself. I remembered that Buckminster Fuller had been harping on this at a recent lecture — that people perceived the Earth as flat and infinite, and that that was the root of all their misbehavior. Now from my altitude of three stories and one hundred mikes, I could see that it was curved, think it, and finally feel it. But how to broadcast it?”

Scribbled in his journal entry for that day was the answer, in the form of a question: “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole earth yet?”

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union competed for nuclear dominion on Earth. With the 01957 launch of Sputnik, the contest expanded to space. But in the race to the moon, neither side had given much thought to the value of training their satellites’ apertures on the world left behind. Brand glimpsed the power such an image could hold.

“A photograph would do it — a color photograph from space of the earth,” Brand said. “There it would be for all to see, the earth complete, tiny, adrift, and no one would ever perceive things the same way.”

Brand mounted a spirited campaign selling buttons that posed the question “Why Haven’t We Seen A Photograph of the Whole Earth?” on college campuses across the country. He often showed up in costume, and he often was chucked out by security. He sent buttons to Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, NASA officials, and members of Congress.

According to a 01966 Village Voice article, a student at Columbia asked Brand: “What would happen if we did have a picture? Would it eliminate slums, or meanness, or anything?”

“Maybe not,” said Brand, “but it might tell us something about ourselves.”

“What?” asked the girl.

“It might tell us where we’re at,” said Brand.

“What for?” asked the girl.

“Why do you look in the mirror?” asked Brand.

“Oh,” said the girl, and bought a button.

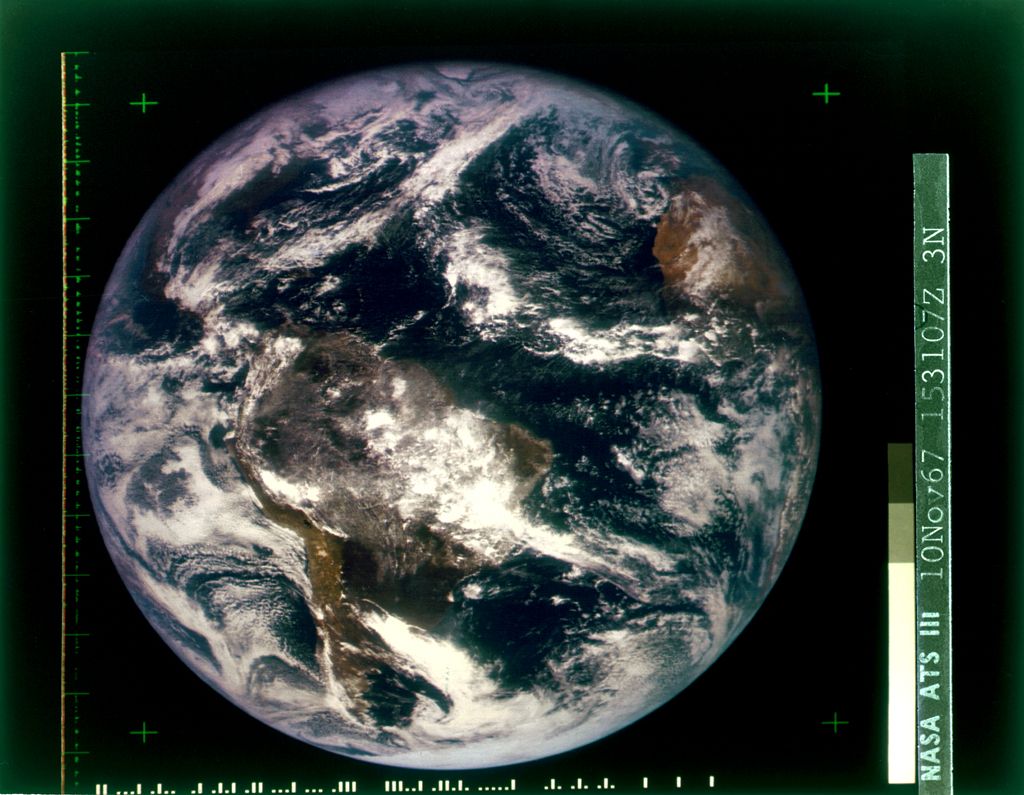

Brand would soon get his photo. On November 10, 01967, the NASA geostationary weather and communications satellite ATS-3 captured the first color photograph of the whole earth. Brand used a reproduction of the photo for the cover of the first Whole Earth Catalog, a countercultural bible and forerunner to the World Wide Web that Steve Jobs once called “Google in paperback form.”

But the image didn’t enter the mainstream, as the first copies of The Whole Earth Catalog seldom strayed far from the communes. (That would change by 01972, when The Last Whole Earth Catalog won a National Book Award).

The moment of revelation for a global audience came in 01968, at the conclusion of a year of violence and unrest that saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, the escalation of war in Vietnam, and the brutal suppression of student protests across the globe.

During the Apollo 8 lunar mission on Christmas Eve, 01968, Astronauts Frank Borman, James Lovell, and Bill Anders left Earth’s orbit for the moon, traveling further than any humans before. And then they looked back.

Anders later said the view of a fragile earth hanging suspended in the void “caught us hardened test pilots.”

“Here we came all this way to the Moon, and yet the most significant thing we’re seeing is our own home planet, the Earth. “— Astronaut Bill Anders

The descriptions of awe, connection, and transcendence Lowell, Borman and Anders said they felt that day when they looked back at Earth would be echoed by future astronauts.

“You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, ‘Look at that, you son of a bitch.’” — Astronaut Edgar Mitchell

Psychologists call this cognitive shift of awareness during spaceflight the “overview effect.”

The Apollo 8 astronauts reached for their cameras and started snapping photos. Later that day, in what was, at that time, the most watched television broadcast in history, the astronauts read from the Book of Genesis as the cameras showed a grainy, black and white image of the Earth.

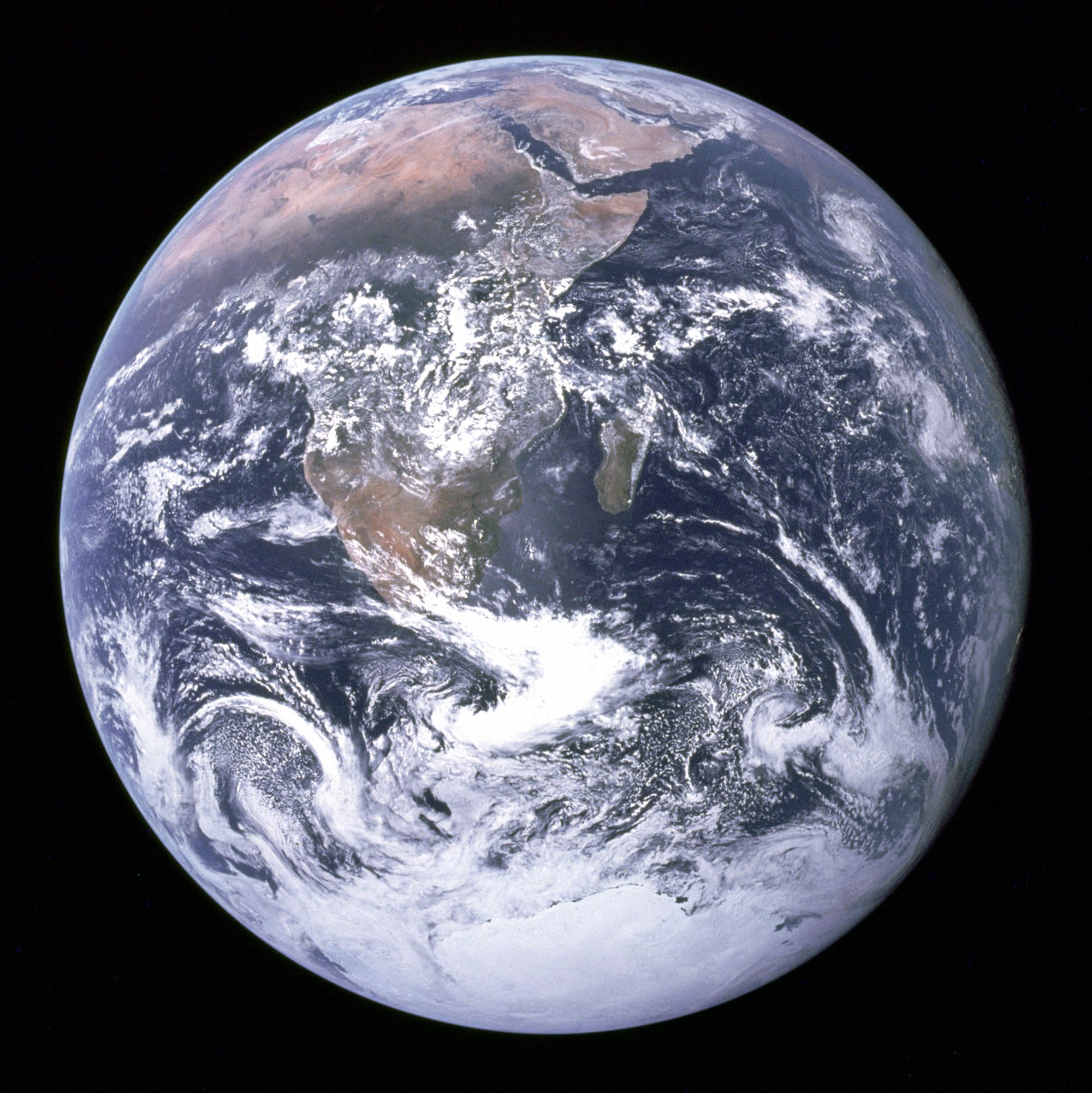

When the astronauts returned to Earth three days later, they brought with them the boon of their new whole earth perspective in the form of a photograph. Earthrise captured what the grainy television cameras could not.

“Up there, it’s a black-and-white world,” James Lovell later recalled. “There’s no color. In the whole universe, wherever we looked, the only bit of color was back on Earth…It was the most beautiful thing there was to see in all the heavens.”

Earthrise and its companion Blue Marble (01972) are among the most widely disseminated images in human history. By approximating the overview effect for the earthbound, the photos helped launch the modern environmental movement and reframed how we think about our relationship to the planet.

“The sight of the whole Earth, small, alive, and alone, caused scientific and philosophical thought to shift away from the assumption that the Earth was a fixed environment, unalterably given to humankind, and towards a model of the Earth as an evolving environment, conditioned by life and alterable by human activity,” writes historian Robert Poole.² “It was the defining moment of the twentieth century.”

Be that as it may, historian Benjamin Lazier argues that by the twenty-first century, Earthrise and Blue Marble became victims of their own success.

“Views of Earth are now so ubiquitous as to go unremarked,” he writes. “These two images and their progeny now grace T-shirts and tote bags, cartoons and coffee cups, stamps commemorating Earth Day and posters feting the exploits of suicide bombers.” The whole earth’s very omnipresence means that “we ceased, in a fashion, to see it.”

Perhaps. Benjamin Grant, founder of the Daily Overview, believes we just need to look closer.

II. An Amazing Mistake

In 02013, Benjamin Grant, then a brand strategist at a buttoned-up consulting firm in New York City, found himself thinking less about marketing and more about outer space. Earlier that year, a meteor whose light shone brighter than the sun exploded into fragments across Russian skies. In September, NASA confirmed that the Voyager space probe entered interstellar space, becoming the first human-made object to leave the solar system. And SpaceX was making strides with the rockets it hoped would one day carry humans to Mars. Grant was fascinated, and decided to start a space club at work.

“It was not a normal thing for anyone at my job to start a club of any kind,” Grant says. “But I figured I would do it and if I got fired for doing it then it probably was not the right place for me to work anyway.”

Grant started giving talks at the firm, and soon became known to his colleagues as the space guy. One introduced him to a short film by Planetary Collective called Overview.

The film explored the overview effect in meditative detail and shared astronauts’ reactions to seeing the earth from space.

“It was so powerful to me, so profound,” Grant says of watching Overview. “Maybe I was searching for something like that.”

Grant began sharing the video with everyone he knew. The overview effect was very much on his mind when he started preparing for a space club talk on GPS satellites. As he was pulling some satellite imagery for the talk, he entered “Earth” into the Apple Maps search bar, hoping it would take him to a zoomed out view of the whole earth. What he saw instead stunned him: Earth, Texas, a small town in the Northern part of the state with a population of 1,048.

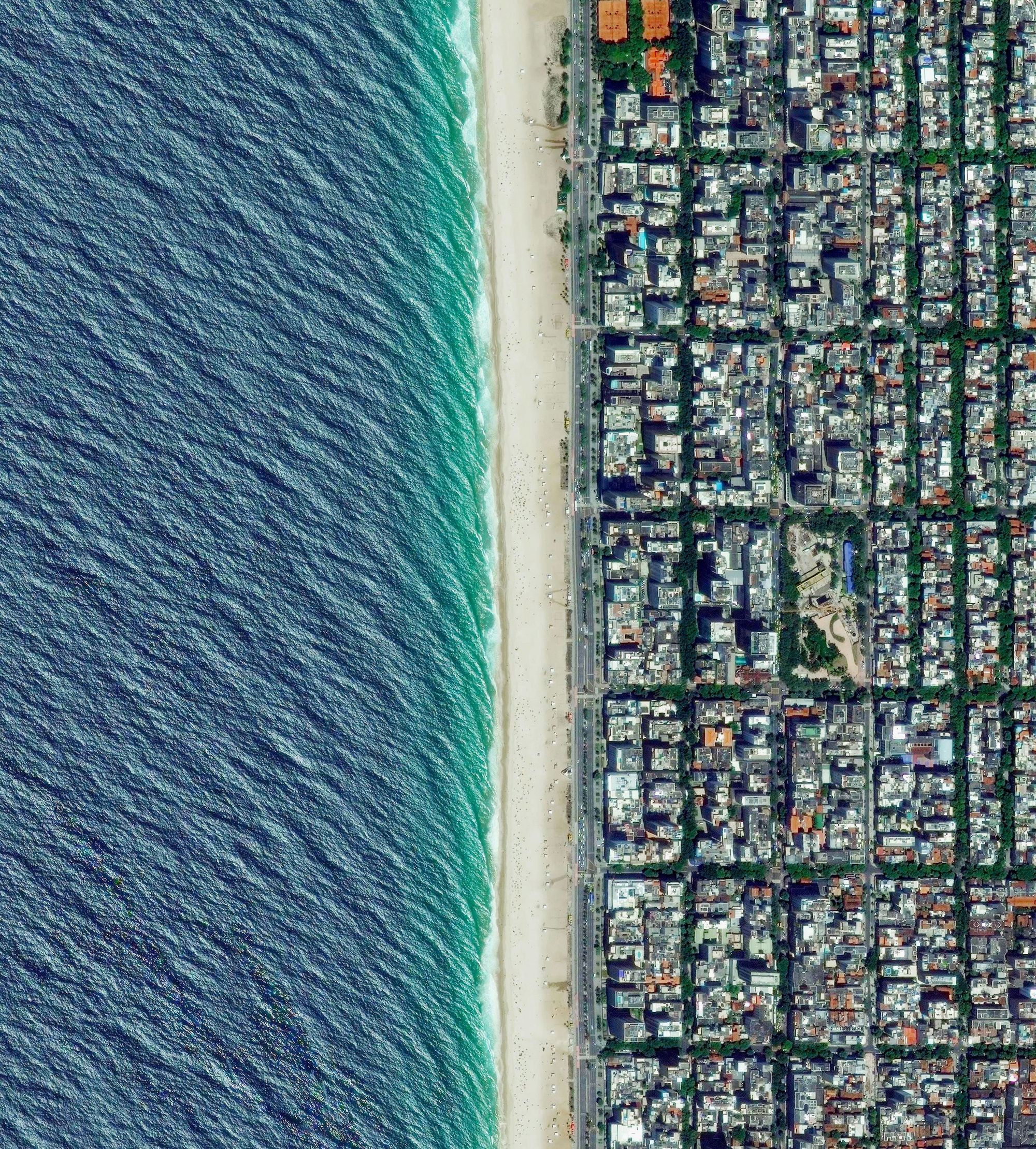

Viewed from above, Earth, Texas is dappled by perfect circle after circle of fields, looking not unlike a pattern of verdant vinyl records.

“I had no idea what I was seeing at the time, but I’d studied art history and was dabbling in photography,” Grant says. “This was so stunningly beautiful and I had absolutely no idea what it was. It was this amazing mistake that set me off on this adventure.”

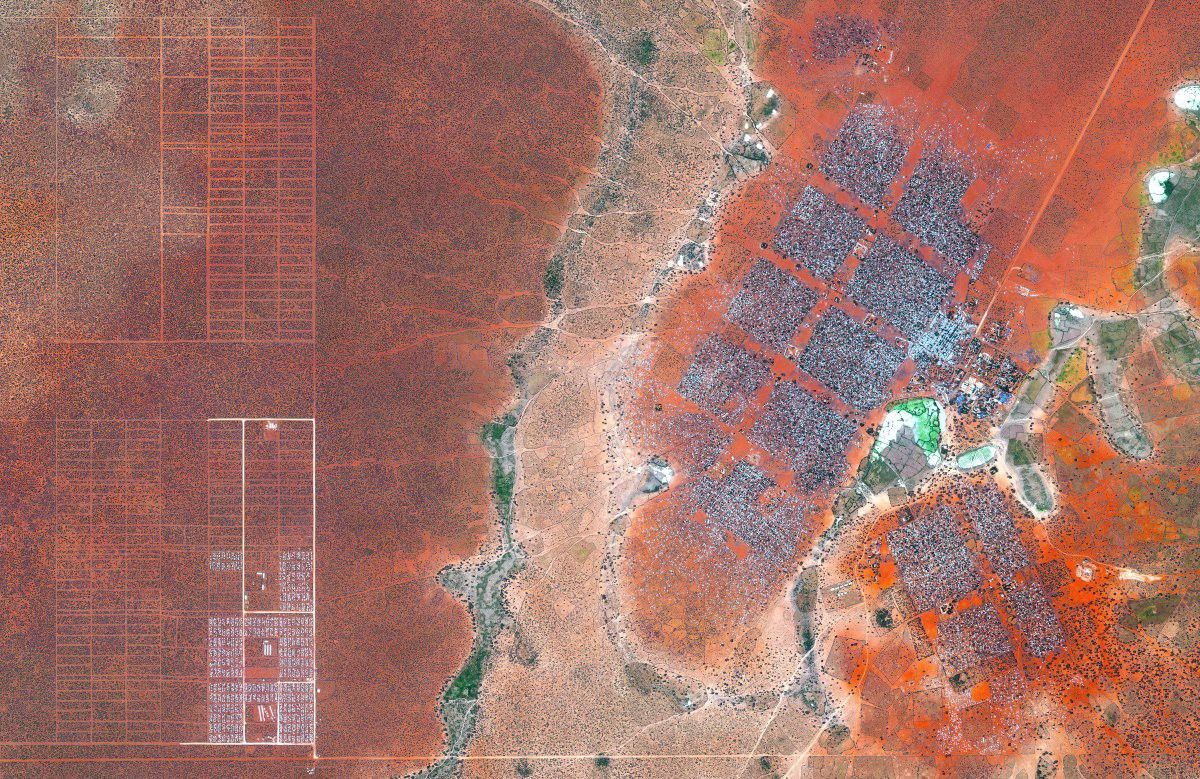

Grant went back to his apartment, plugged his computer into his big-screen, and showed the image to his roommates. They discovered that they were looking at pivot irrigation fields. The image inspired an evening of searching for similarly arresting satellite imagery of man-made systems. A friend from Europe showed him the shipping containers of the Port of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest sea port. Another friend who worked in energy asked if Grant had ever looked at solar concentrators before. A friend’s girlfriend who worked for an NGO at the time showed them the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya.

In an epiphanous moment not unlike Stewart Brand’s whole earth vision—sans LSD—Grant realized that these seldom-considered perspectives might inspire something akin to what seeing the Earth from space did for astronauts.

He launched the Daily Overview on Instagram soon after. Each day, the account shares an image of the Earth from above, called an Overview, that is optimized to capture fleeting attention on social media. Underneath each arresting image is a bite-size caption of two to three sentences describing what you’re seeing, along with geocoordinates. Daily Overview is one of the most popular blogs on social media. On Instagram, no account with an environmental focus has more followers.

“I think we’re inundated and saturated with so much information all the time now,” Grant tells me, “that if you can focus it to a few simple things it can actually stick with someone.”

There’s a key difference between these Overviews and the whole earth photographs of yore: Blue Marble and Earthrise showed a planet seemingly unaffected by human activity. (“Raging nationalistic interests, famines, wars, pestilences don’t show from that distance,” Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman said). Zooming in changes that.

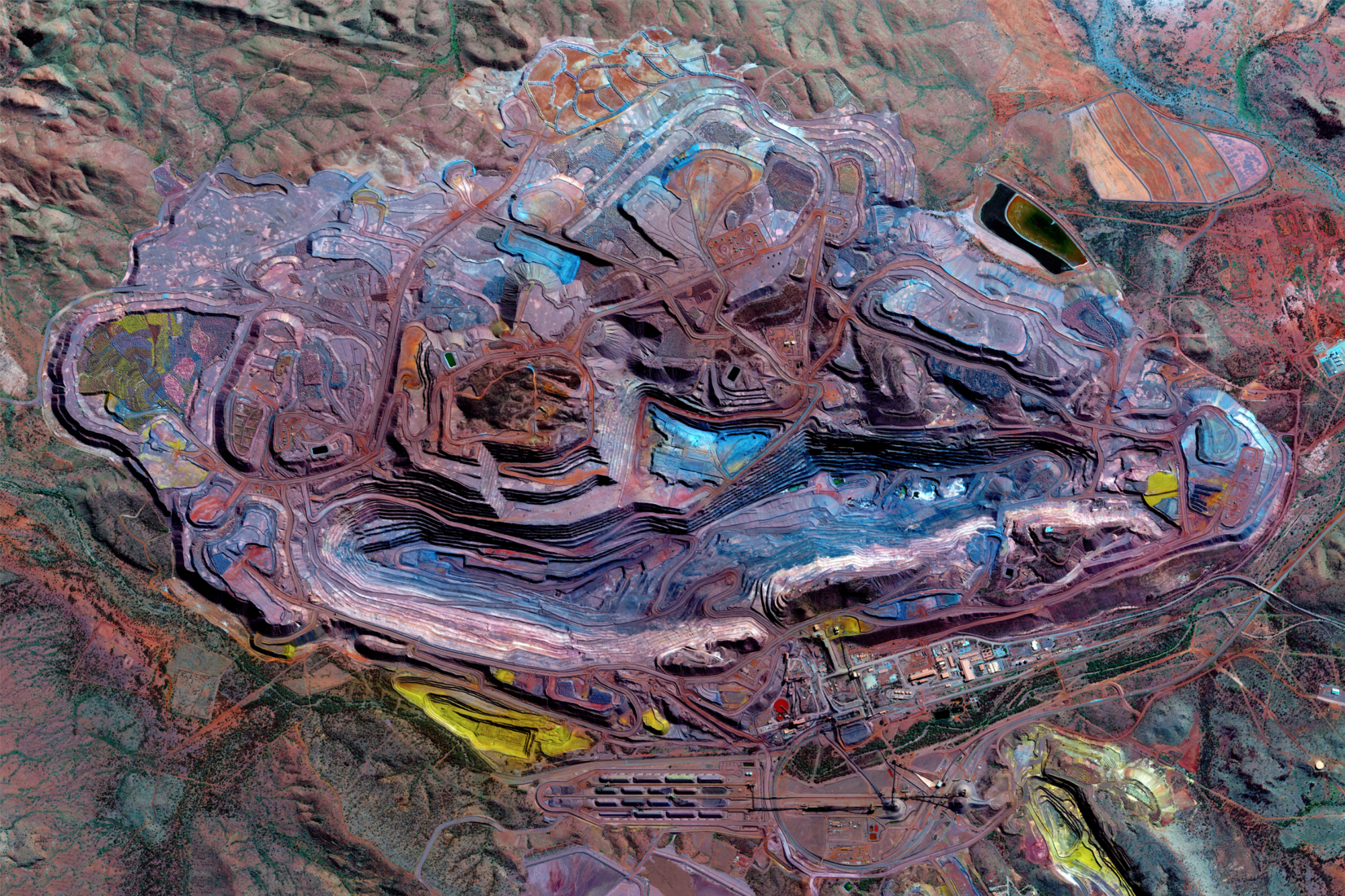

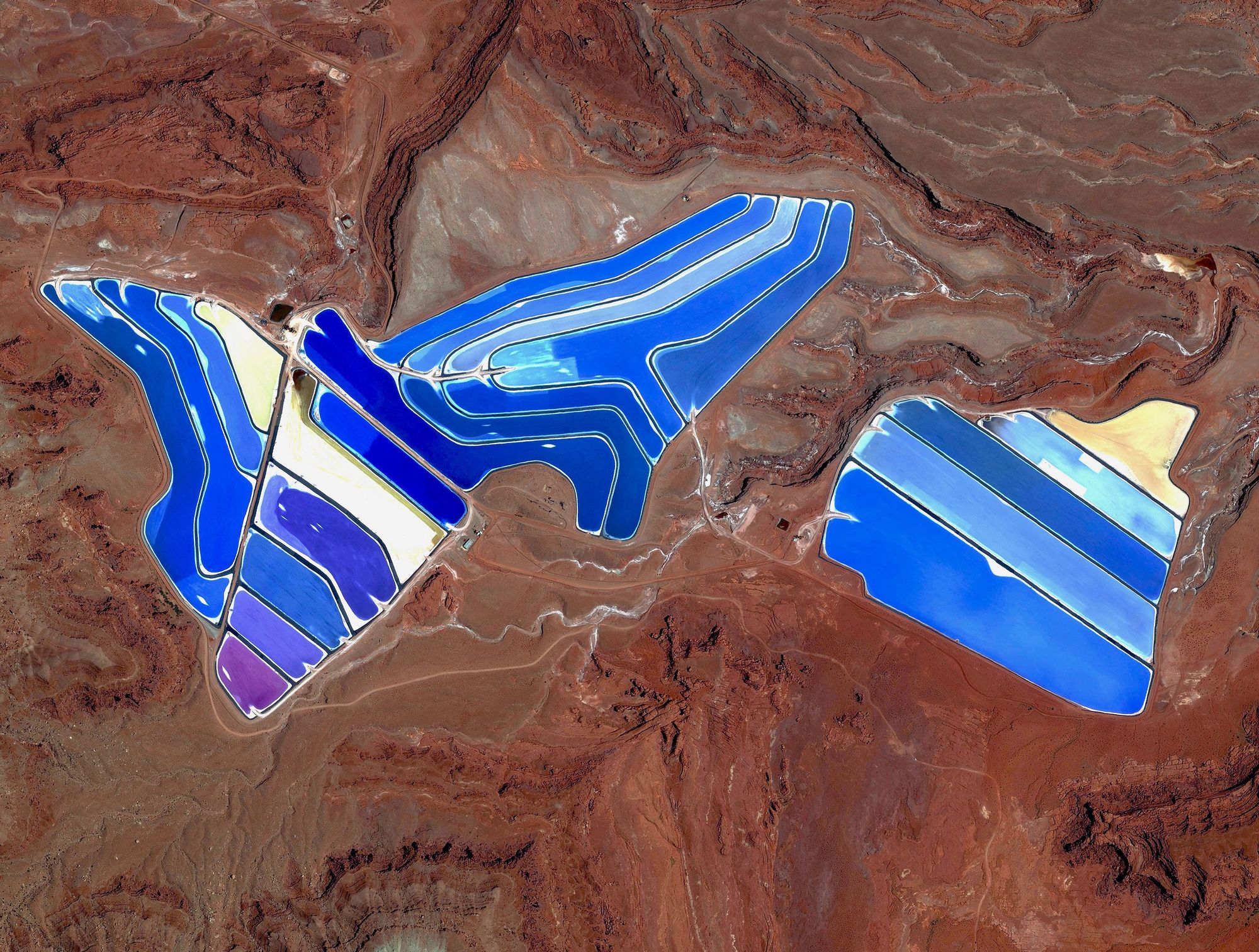

What one witnesses from this vantage — intricate and vibrant patterns of human activity, construction, and destruction— is still aesthetically-pleasing. But in asking how those systems came to be, and learning about their impact, Grant hopes that one gains a planetary awareness, and, ideally, a motivation to act in a way that ensures planetary flourishing.

“If people have a better understanding of what is going on they’re more likely to behave in a way that serves the planet rather than serving themselves,” Grant tells me. “These images are a way to introduce things that people would never look at. If you were like, ‘I want you to look at waste ponds from this iron ore mine,’ people would say, ‘Why would I spend my time doing that?’ But if you can do that in a beautiful way that gets people engaged and gets people to ask questions about why it looks a certain way or is a certain color that’s an opportunity to educate and potentially change behaviors.”

For Grant, inspiring awe with his overviews is as important as inspiring awareness.

“The things that stimulate awe, such as exposure to perceptually vast things, that you can experience if you go to the Grand Canyon or look out your airplane window, results in fascinating behaviors,” Grant says.

A 02014 study found that exposure to perceptually vast stimuli that transcend current frames of reference (i.e., awe) resulted in increased ethical decision making, generosity, and prosocial values while leading to decreased feelings of entitlement. “Awe,” the study’s authors concluded, “may help situate individuals within broader social contexts and enhance collective concern.”

For Grant, stimulating awe with an overview comes down to not just what the satellite image portrays, but its artfulness. Each overview is stitched together out of as many as 25 images, purposefully cropped with balance and composition in mind. Many of Grant’s overviews evoke the works of Piet Mondrian, Mark Rothko, and Ellsworth Kelly.

“My favorite art is abstract expressionist painting—very simple, almost flat two dimensional painting,” Grant says. “When you look at the world from outer space it also appears flat and two dimensional.”

“If I can get people to experience awe,” Grant says, “not only because they’re seeing something that’s visually vast, like seeing an entire city in one frame or an entire mine in one frame, but if also I can compose it in such a way that the artistry of the image itself gets someone to feel awe, perhaps I’m being doubly as effective at getting them to think more prosocially or think beyond themselves or think of the collective.”

III. A New Icon?

Grant’s notions about his overviews as art reminds me of something Stewart Brand once said when asked to elaborate on his intentions with getting NASA to release an image of the earth from space

“I saw the whole earth as an icon, mainly,” he said, “one that did indeed replace the mushroom cloud as the main image for understanding our world.”

These days, Brand’s focus has shifted to a creating a new icon for a different age, The Long Now Foundation’s Clock of the Long Now. “Ideally, it would do for thinking about time what the photographs of Earth from space have done for thinking about the environment,” Brand writes. “Such icons reframe how people think.”

Brand’s co-founder at Long Now, Brian Eno, sees both the whole earth photographs and The Clock of The Long Now as works of art that are imbued with a “mythic, metaphorical presence.”

“The 20th Century yielded its share of icons,” Eno writes. “In this, the 21st century, we may need icons more than ever before.”

Grant’s overviews present the Earth in piecemeal — fragments of a larger whole delivered to a global audience on platforms engineered for ephemerality.

When asked if he thinks it’s possible for a single image of the Earth to serve as an icon for our current age like the whole Earth photos did half a century ago, Grant says he doesn’t think so.

“I don’t know if you could unify people in that way now,” he says. “It’s certainly necessary.”

Nonetheless, Grant believes advances in technology and the current space revolution will make the overview effect more and more a part of our lives. Geostationary satellites with better cameras are creating new Blue Marbles. Space tourism is on the rise, with trips to Mars on the horizon. The perspective the whole earth icon points to could—for those fortunate enough to “slip the surly bonds of earth”—become a direct experience.

“The overview effect is going to become more of a thing,” Grant says. “Whether or not it’s called that, or whether or not people are experiencing it first hand…if awe is generated, regardless of how it happens, it will lead to more prosocial values and more collaboration, and that will create a better planet.”

Notes

[1] The Long Now Foundation uses five digit dates to serve as a reminder of the time scale that we endeavor to work in. Since the Clock of the Long Now is meant to run well past the Gregorian year 10,000, the extra zero is to solve the deca-millennium bug which will come into effect in about 8,000 years.

[2] Poole, Robert. Earthrise: How Man First Saw the Earth (02008), Yale University Press, 198–9.

Learn More

- Watch Benjamin Grant’s Long Now talk and conversation with Stewart Brand.

- Read Benjamin Grant’s book about the Daily Overview project, Overview(02016).

- Read “The Overview Effect: Awe and Self-Transcendent Experience in Space Flight” in Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice (02016), Vol. 3, №1, 1–11.

- Read “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior” in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (02015), Vol. 108, №6, 883–899.

- Read “The Man Who Changed The World, Twice” by David Brooks.

- Watch Benjamin Grant’s 02017 TED talk.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe