The Permanent Legacy Foundation Wants to Preserve Your Digital Legacy for Future Generations

Digital storage is easy; digital preservation is hard.

In March of 02019, MySpace, the one-time de facto social media network before the rise of Facebook, announced that it had lost 12 years’ worth of users’ songs, photos, and videos during a data migration. In emails to angry users who demanded to know what happened to their data, the company admitted there was no way to recover it. A sizable chunk of internet history was lost forever.

MySpace’s data loss is a harbinger of what we at Long Now call a digital dark age. All of our digital platforms and systems, from the social media networks we post on every day, to the storage services we rely on to back up our most important files, to the infrastructures that power our digital world economy, are vulnerable to irretrievable data loss. Over time, file formats, applications, and operating systems go obsolete. Legacy systems become impenetrable. The migration of data to new systems risks breaking the chain of information transmission.

“In personal terms the loss seems merely an inconvenience, the price of progress,” Long Now Co-Founder Stewart Brand wrote in Clock of the Long Now (01999). “But in terms of civilization the loss is catastrophic. Just when we think at last, thanks to digitization, everything we want to keep can be preserved forever, the reality is precisely the opposite.”

There has been progress toward preventing a digital dark age in the two decades since Brand wrote those words. The Internet is being archived. Electronic file formats and digital storage are being standardized. Open source software is being adopted by institutions across the world. But on the individual level, the risk of losing one’s digital legacy remains.

A new cultural heritage nonprofit organization is hoping to eliminate that risk. The Permanent Legacy Foundation was founded to ensure that the digital legacy of all people is preserved in perpetuity for the historical and educational benefit of future generations.

“In the rush to digitize all of human knowledge and experience, we’ve put an emphasis on availability now, but have neglected to design for long term preservation,” Robert Friedman, the Executive Director of Permanent, says. “The same digital technology that has made it possible to connect everyone on Earth also makes it possible for everyone to be remembered as a contributor to a shared history. Preservation for every person is now within reach but it requires a fundamentally new kind of organization.”

Permanent aims to become that organization by applying the curatorial, preservation, and funding models of museums, libraries, and archives to commercial cloud storage technology. Similar to other cloud storage services, Permanent allows users to store and access the content they need right now. It distinguishes itself by its focus on preserving that content over the Long Now.

Permanent’s security and access strategy for multi-generational data has three components to it: a public legacy, a private legacy, and a right to be forgotten. This flexibility enables users to curate their digital legacy according to their long-term wishes. Say you’re a writer. You might want to make certain parts of your content public while you’re alive and after you’re gone: your published and unpublished work, noteworthy correspondence, rejection letters, photos of you accepting awards, et cetera. In so doing, you allow future descendants to better understand you, and future historians to better understand our time.

But you might not want to make all of your content public: legal documents, private family photos, videos, personal correspondence, et cetera. Those you entrust as stewards over your digital legacy can access those sensitive files, and later choose to release them.

Then there’s the content you might want to store, but never share with anyone. Permanent’s right to be forgotten allows for materials to be stored in a double-encrypted “vault.” Only those who have the encryption key can unlock the materials. Similar to how cryptocurrency encryption works, once the key is lost, the material cannot be accessed.

A user will be able to set the rules for each file they store via Permanent’s Directives. Say you’ve written a poem about the year 09999 that you’d like to be publicly released on December 31st of that year, or a novella about Mars that you want published on the occasion of the first human being born on the Red Planet. “Directives can trigger a change of permissions, ownership, public status, or bury materials based on specific events or dates,” Friedman says.

“As part of the Permanent mission to ensure the preservation of the digital legacy of all people, we encourage our users to make as much of their personal memories public as possible,” Friedman says. “Materials that do not have specific directives set will be made public by default after the death of their owners and the expiration of their copyright.”

There’s a high likelihood that that poem written about the year 09999 was saved in a file format that will no longer exist by 09999. To maintain accessibility to your materials, Permanent promises to convert the formats as technology evolves. Additional measures to ensure accessibility include storing the materials with commercial storage partners, creating redundant backups, and migrating the data.

Permanent maintains its archival integrity through reading metadata and allowing users to edit it; providing historical context through features like user profiles, members, and relationships; restoring file integrity via backups whenever a file becomes corrupted; and employing a LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe) approach to archiving your digital legacy.

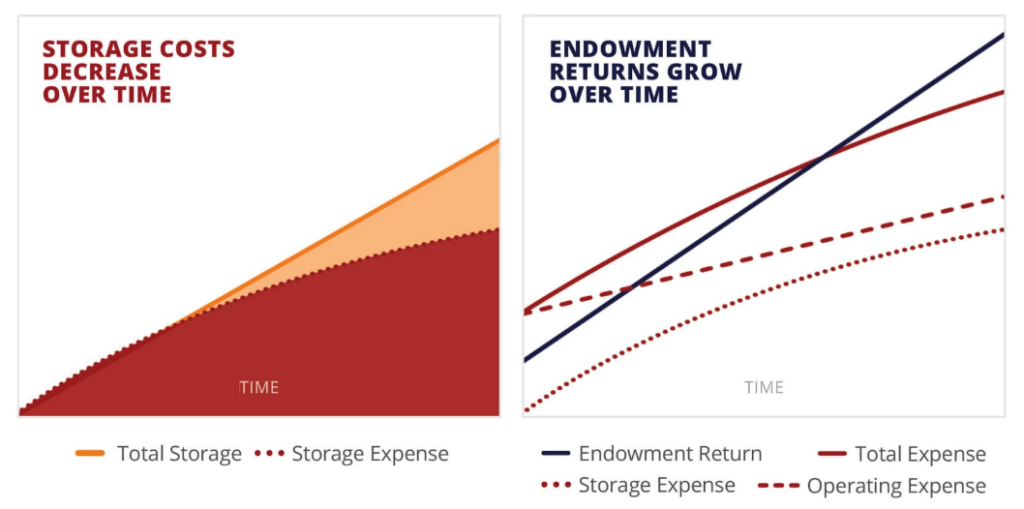

To ensure its viability as a long-lived institution, Permanent uses a Non-Profit Endowment model, much like how museums and universities operate. “Instead of a recurring monthly fee, users pay a one-time storage fee and the money is put into an investment account (an endowment) whose purpose is sustainability,” Friedman says. “The returns or interest on the endowment cover the continued cost of storage. Our model converts that one-time ‘micro-endowment’ donation into perpetual storage.”

“The goal is for the endowment to provide, at the very minimum, permanent storage of users’ materials and the capability to download these materials at any time,” Friedman says. “But it’s not just the cost of storage — these fees also support an organization committed to protecting, migrating, and maintaining access to user content for all time.”

For that goal to be met, Permanent’s endowment needs to reach a critical mass. The organization is currently raising funds, with a goal of $100,000. As of this writing, it’s more than two-thirds of the way there.

“If we make it possible to preserve the legacy of every individual and make that legacy accessible to future generations,” Friedman says, “then we can create a resource to transform the idea of human history as we know it.”

Permanent is offering followers of The Long Now Foundation 10 gigabytes of free archival storage when you sign up through this page.

Learn More

- Robert Friedman, “Democratizing Permanence to Create an Inclusive History” in Permanent.

- Alexis Madrigal, “Future Historians Probably Won’t Understand Our Internet, and That’s Okay” in The Atlantic.

- Clifford Lynch, “Stewardship in the ‘Age of Algorithms’” in First Monday.

- Ahmed Kabil, “Long Now Partners with GitHub on its Long-term Archive Program for Open Source Code” in Long Now.

- Long Now’s summary of the “Time & Bits: Managing Digital Continuity” conference at the Getty Center in 01998.

- Browse our blog posts on the Digital Dark Age.

- Examples of how individuals and organizations are using Permanent’s archives.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe