The Other 10,000 Year Project: Long-Term Thinking and Nuclear Waste

The questions around nuclear waste storage — how to keep it safe from those who might wish to weaponize it, where to store it, by what methods, for how long, and with what markings, if any, to warn humans who might stumble upon it thousands of years in the future—require long-term thinking.

I. “A Clear and Present Danger.”

“For anyone living in SOCAL, San Onofre nuclear waste is slated to be buried right underneath the sands,” tweeted @JoseTCastaneda3 in February 02017. “Can we say ‘Fukushima #2’ yet?”

The “San Onofre” the user was referring to is the San Onofre nuclear plant in San Diego County, California, which sits on scenic bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean and sands dotted with surfers and beach umbrellas. Once a provider of eighteen percent of Southern California’s energy demands, San Onofre is in the midst of a 20-year, $4.4 billion demolition project following the failure of replacement steam generators in 02013. At the time, Senator Barbara Boxer said San Onofre was “unsafe and posed a danger to the eight million people living within fifty miles of the plant,” and opened a criminal investigation.

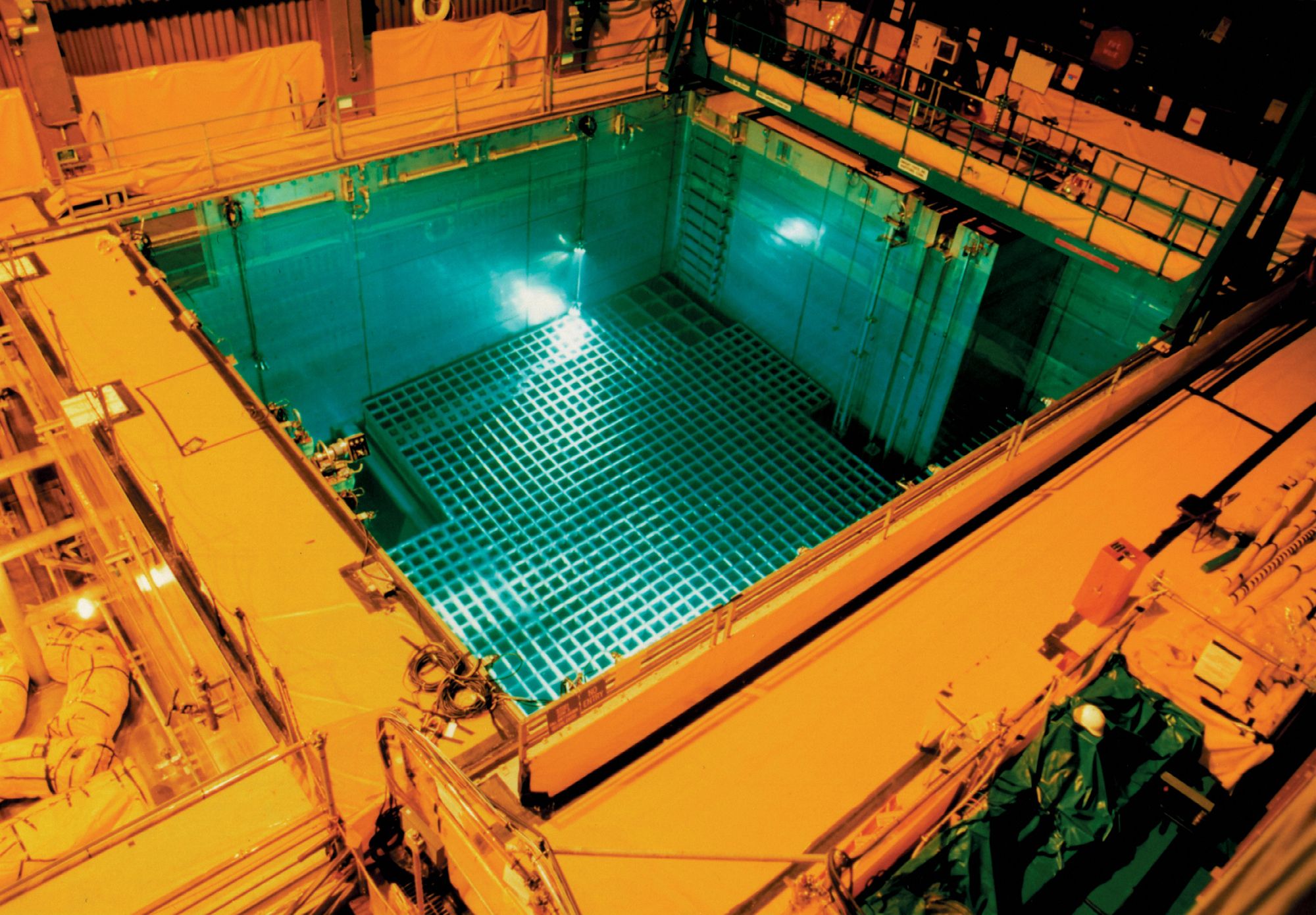

A part of the demolition involved figuring out what to do with the plant’s millions of pounds of high-level waste (the “spent fuel” leftover after uranium is processed) that simmered on-site in nuclear pools. It was decided that the nuclear waste would be transported a few hundred yards to the beach, where it would be buried underground in what local residents have taken to calling the “concrete monolith” – a state of the art dry cask storage container that will house 75 concrete-sealed tubes of San Onofre’s nuclear waste until 2049.

This has left a lot of San Diego County residents unhappy.

“We held a sacred water ceremony today @ San Onofre where 3.6mm lbs of nuclear waste are being buried on the beach near the San Andreas faultline,” tweeted Gloria Garrett, hinting at a nuclear calamity to come.

Congressman Darrell Issa, who represents the district of the decommissioned plant and introduced a bill in February 02017 to relocate the waste from San Onofre, was concerned about the bottom line.

“It’s just located on the edge of an ocean and one of the busiest highways in America,” Issa said in an interview with the San Diego Tribune. “We’ll be paying for storage for decades and decades if we don’t find a solution. And that will be added to your electricity bill.”

“The issue of what to do with nuclear waste is a clear and present danger to every human life within 100 miles of San Onofre,” said Charles Langley of the activist group Public Watchdogs.

“Everyone is whistling past the graveyard, including our regulators,” Langley continued. “They are storing nuclear waste that is deadly to humans for 10,000 generations in containers that are only guaranteed to last 25 years.”

II. The Nuclear Waste Stalemate

Nobody wants a nuclear waste storage dump in their backyards.

That is, in essence, the story of America’s pursuit of nuclear energy as a source of electricity for the last sixty years.

In 01957, the first American commercial nuclear reactor opened in the United States. That same year, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommended that spent fuel should be transported from reactors and buried deep underground. Those recommendations went largely unheeded until the Three Mile Island meltdown of March 01979, when 40,000 gallons of radioactive wastewater from the reactor poured into Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna River.

The political challenge of convincing any jurisdiction to store nuclear waste for thousands of years has vexed lawmakers ever since. As Marcus Stroud put it in his in-depth 02012 investigative feature into the history of nuclear waste storage in the United States:

Though every presidential administration since Eisenhower’s has touted nuclear power as integral to energy policy (and decreased reliance on foreign oil), none has resolved the nuclear waste problem. The impasse has not only allowed tens of thousands of tons of radioactive waste to languish in blocks of concrete behind chain link fences near major cities. It has contributed to a declining nuclear industry, as California, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Oregon, and other states have imposed moratoriums against new power plants until a waste repository exists. Disasters at Fukushima, Chernobyl, and Three Mile Island have made it very difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to build a nuclear reactor because of insurance premiums and strict regulations, and the nuclear waste stalemate has added significantly to the difficulties and expenses. Only two new nuclear power plants have received licenses to operate in the last 30 years.

Yucca Mountain was designated as the site for a national repository of nuclear waste in the Nuclear Waste Act of 01987. It was to be a deep geological repository for permanently sealing off and storing all of the nation’s nuclear waste, one that would require feats of engineering and billions of dollars to build. Construction began in the 01990s. The repository was scheduled to open and begin accepting waste on March 21, 02017.

But pushback from Nevadans, who worried about long-term radiation risks and felt that it was unfair to store nuclear waste in a state that has no nuclear reactors, left the project defunded and on indefinite hiatus since 02011.

Today, nuclear power provides twenty percent of America’s electricity, producing almost 70,000 tons of waste a year. Most of the 121 nuclear sites in the United States opt for the San Onofre route, storing waste on-site in dry casks made of steel and concrete as they wait for the Department of Energy to choose a new repository.

III. Opening Ourselves to Deep Time

“We must have the backbone to look these enormous spans of time in the eye. We must have the courage to accept our responsibility as our planet’s – and our descendants’ – caretakers, millennium in and millennium out, without cowering before the magnitude of our challenge.” —Vincent Ialenti

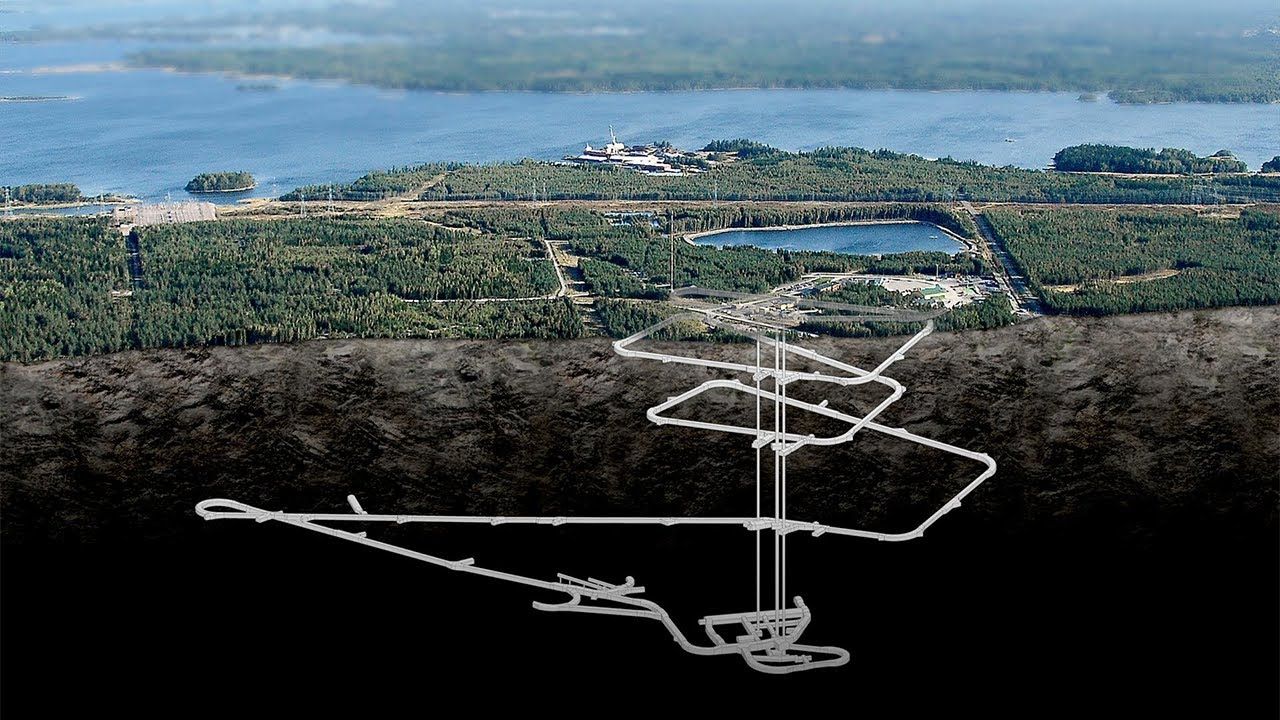

An aerial view of Posiva Oy’s prospective nuclear waste repository site in Olkiluoto, Finland / via Posiva Oy

Anthropologist Vincent Ialenti recently spent two years doing field work with a Finnish team of experts who were in the process of researching the Onkalo long term geological repository in Western Finland that, like Yucca Mountain, would store all of the Finland’s nuclear waste. The Safety Case project, as it was called, required experts to think in deep time about the myriad of factors (geological, ecological, and climatological) that might affect the site as it stored waste for thousands of years.

Ialenti’s goal was to examine how these experts conceived of the future:

What sort of scientific ethos, I wondered, do Safety Case experts adopt in their daily dealings with seemingly unimaginable spans of time? Has their work affected how they understand the world and humanity’s place within it? If so, how? If not, why not?

In the process, Ialenti found that his engagement with problems of deep time (“At what pace will Finland’s shoreline continue expanding outward into the Baltic Sea? How will human and animal populations’ habits change? What happens if forest fires, soil erosion or floods occur? How and where will lakes, rivers and forests sprout up, shrink and grow? What role will climate change play in all this?”) changed the way he conceived of the world around him, the stillness and serenity of the landscapes transforming into a “Finland in flux”:

I imagined the enormous Ice Age ice sheet that, 20,000 years ago, covered the land below. I imagined Finland decompressing when this enormous ice sheet later receded — its shorelines extending outward as Finland’s elevation rose ever higher above sea level. I imagined coastal areas of Finland emerging from the ice around 10,000 BC. I imagined lakes, rivers, forests and human settlements sprouting up, disappearing and changing shape and size over the millennia.

Ialenti’s field work convinced him of the necessity of long-term thinking in the Anthropocene, and that engaging with the problem of nuclear waste storage, unlikely though it may seem, is a useful way of inspiring it:

Many suggest we have entered the Anthropocene — a new geologic epoch ushered in by humanity’s own transformations of Earth’s climate, erosion patterns, extinctions, atmosphere and rock record. In such circumstances, we are challenged to adopt new ways of living, thinking and understanding our relationships with our planetary environment. To do so, anthropologist Richard Irvine has argued, we must first “be open to deep time.” We must, as Stewart Brand has urged, inhabit a longer “now.”

So, I wonder: Could it be that nuclear waste repository projects — long approached by environmentalists and critical intellectuals with skepticism — are developing among the best tools for re-thinking humanity’s place within the deeper history of our environment? Could opening ourselves to deep, geologic, planetary timescales inspire positive change in our ways of living on a damaged planet?

IV. How Long is Too Long?

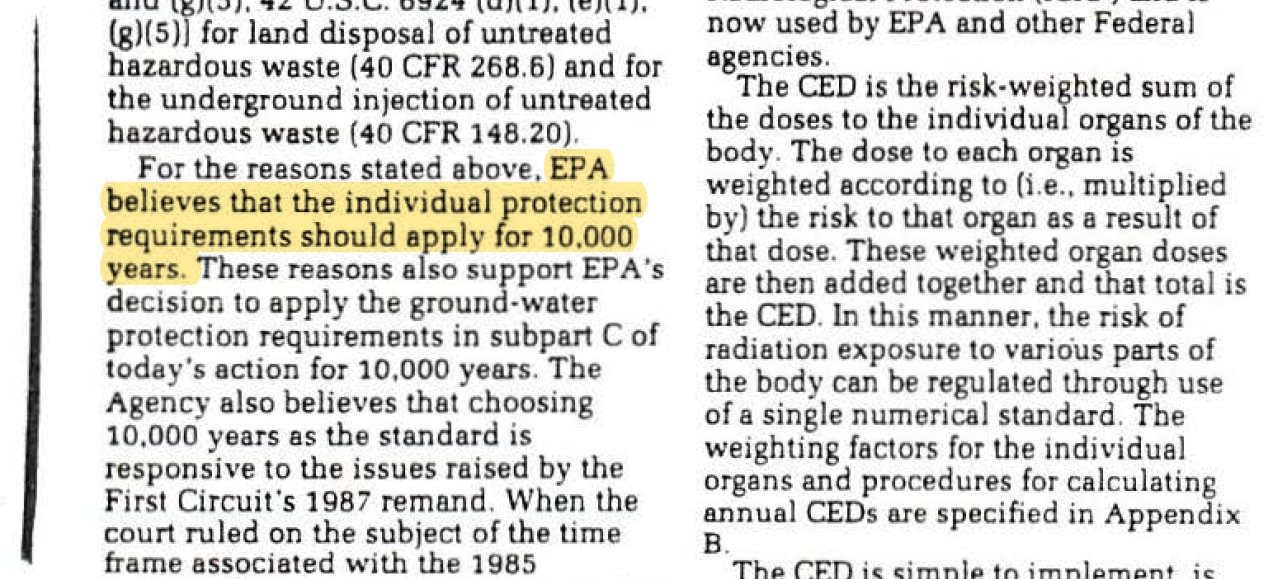

Finland’s Onkalo Repository is designed to last for 100,000 years. In the 01990s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency decided that a 10,000 year-time span was how long a U.S. nuclear waste storage facility must remain sealed off, basing their decision in part on the predicted frequencies of ice ages.

But as Stroud reports, it was basically guesswork:

Later, [the 10,000-year EPA standard] was increased to a million years by the U.S. Court of Appeals in part due to the long half lives of certain radioactive isotopes and in part due to a significantly less conservative guess.

The increase in time from 10,000 years to 1 million years made the volcanic cones at Yucca look less stable and million-year-old salt deposits — like those found in New Mexico — more applicable to the nuclear waste problem.

[The Department of Energy] hired anthropologists to study the history of language—both at Yucca and at the WIPP site in New Mexico—to conceive of a way to communicate far into the future that waste buried underground was not to be disturbed.

But the Blue Ribbon Commission’s report [of 02012] calls these abstract time periods a little impractical.

“Many individuals have told [BRC] that it is unrealistic to have a very long (e.g., million-year) requirement,” it reads. “[BRC] agrees.”

It then points out that other countries “have opted for shorter timeframes (a few thousand to 100,000 years), some have developed different kinds of criteria for different timeframes, and some have avoided the use of a hard ‘cut-off’ altogether.” The conclusion? “In doing so, [these countries] acknowledge the fact that uncertainties in predicting geologic processes, and therefore the behavior of the waste in the repository, increase with time.”

In a spirited 02006 Long Now debate between Global Business Network co-founder and Long Now board member Peter Schwartz and Ralph Cavanagh of the Nuclear Resources Defense Council, Cavanagh pressed Schwartz on the problem of nuclear waste storage.

Schwartz contended that we’ve defined the nuclear waste problem incorrectly, and that reframing the time scale associated with storage, coupled with new technologies, would ease concerns among those who take it on:

The problem of nuclear waste isn’t a problem of storage for a thousand years or a million years. The issue is storing it long enough so we can put it in a form where we can reprocess it and recycle it, and that form is probably surface storage in very strong caskets in relatively few sites, i.e., not at every reactor, and also not at one single national repository, but at several sites throughout the world with it in mind that you are not putting waste in the ground forever where it could migrate and leak and raise all the concerns that people rightly have about nuclear waste storage. By redesigning the way in which you manage the waste, you’d change the nature of the challenge fundamentally.

Schwartz and other advocates of recycling spent fuel have discussed new pyrometallurgical technologies for reprocessing that could make nuclear power “truly sustainable and essentially inexhaustible.” These emerging pyro-processes, coupled with faster nuclear reactors, can capture upwards of 100 times more of the energy and produce little to no plutonium, thereby easing concerns that the waste could be weaponized. Recycling spent fuel would vastly reduce the amount of high-level waste, as well as the length of time that the waste must be isolated. (The Argonne National Laboratory believes its pyrochemical processing methods can drop the time needed to isolate waste from 300,000 years to 300 years).

There’s just one problem: the U.S. currently does not reprocess or recycle its spent fuel. President Jimmy Carter banned the commercial reprocessing of nuclear waste in 01977 over concerns that the plutonium in spent fuel could be extracted to produce nuclear weapons. Though President Reagan lifted the ban in 01981, the federal government has for the most part declined to provide subsidies for commercial reprocessing, and subsequent administrations have spoken out against it. Today, the “ban” effectively remains in place.

When the ban was first issued, the U.S. expected other nuclear nations like Great Britain and France to follow suit. They did not. Today, France generates eighty percent of its electricity from nuclear power, with much of that energy coming from reprocessing and recycling spent fuel. Japan and the U.K reprocess their fuel, and China and India are modeling their reactors on France’s reprocessing program. The United States, on the other hand, uses less than five percent of its nuclear fuel, storing the rest as waste.

In a 02015 op-ed for Forbes, William F. Shughart, research director for the Independent Institute in Oakland, California, argued that we must lift the nuclear recycling “ban” and take full advantage our nuclear capacity if we wish to adequately address the threats posed by climate change:

Disposing of “used” fuel in a deep-geologic repository as if it were worthless waste – and not a valuable resource for clean-energy production – is folly.

Twelve states have banned the construction of nuclear plants until the waste problem is resolved. But there is no enthusiasm for building the proposed waste depository. In fact, the Obama administration pulled the plug on the one high-level waste depository that was under construction at Nevada’s Yucca Mountain.

The outlook might be different if Congress were to lift the ban on nuclear-fuel recycling, which would cut the amount of waste requiring disposal by more than half. Instead of requiring a political consensus on multiple repository sites to store nuclear plant waste, one facility would be sufficient, reducing disposal costs by billions of dollars.

By lifting the ban on spent fuel recycling we could make use of a valuable resource, provide an answer to the nuclear waste problem, open the way for a new generation of nuclear plants to meet America’s growing electricity needs, and put the United States in a leadership position on climate-change action.

According to Stroud, critics of nuclear processing cite its cost (a Japanese government report from 02004 found reprocessing to be four times as costly as non-reprocessed nuclear power); the current abundance of uranium (Stroud says most experts agree that “if the world’s needs quadrupled today, uranium wouldn’t run out for another eighty years”); the fact that while reprocessing produces less waste, it still wouldn’t eliminate the need for a site to store it; and finally, the risk of spent fuel being used to make nuclear weapons.

Shughart, along with Schwartz and many others in the nuclear industry, feels the fears of nuclear proliferation from reprocessing are overblown:

The reality is that no nuclear materials ever have been obtained from the spent fuel of a nuclear power plant, owing both to the substantial cost and technical difficulty of doing so and because of effective oversight by the national governments and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

V. Curiosity Kills the Ray Cat

Whether we ultimately decide to store spent fuel for 10,000 years in a sealed off repository deep underground or for 300 years in above-ground casks, there’s still the question of how to effectively mark nuclear waste to warn future generations who might stumble upon it. The languages we speak now might not be spoken in the future, so the written word must be cast aside in favor of “nuclear semiotics” whose symbols stand the test of time.

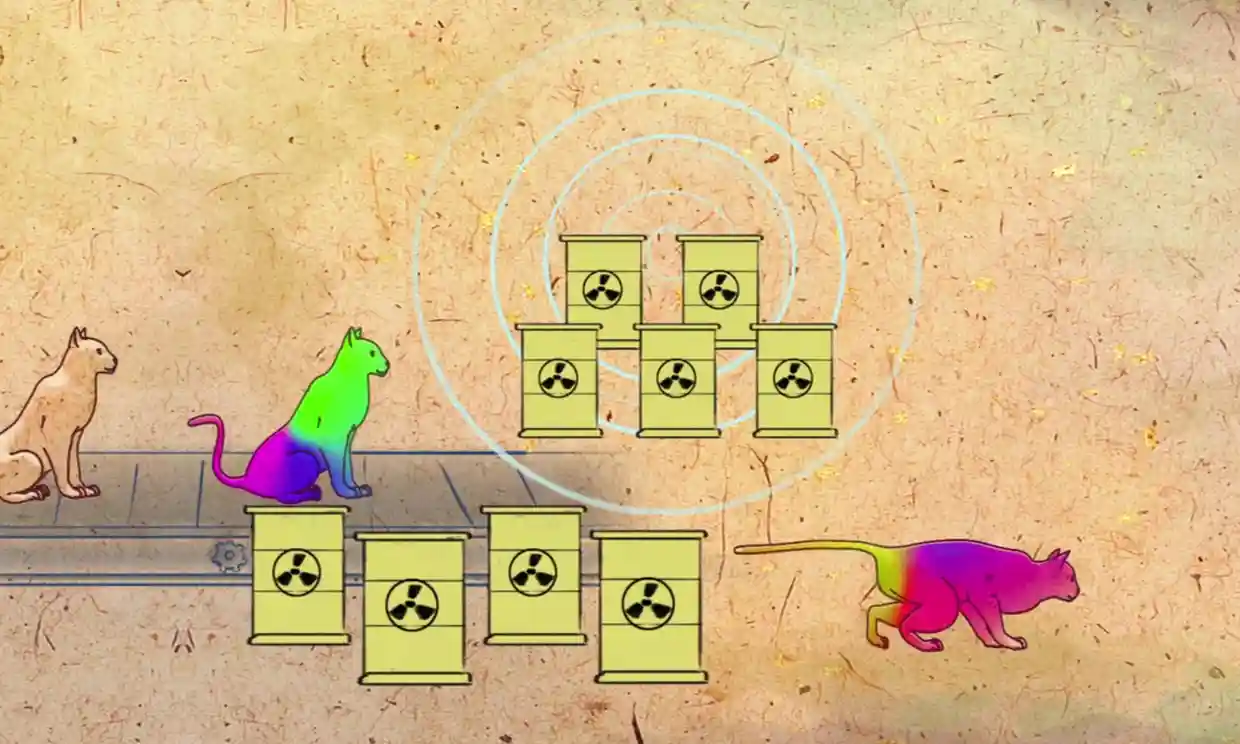

After the U.S. Department of Energy assembled a task force of anthropologists and linguists to tackle the problem in 01981, French author Françoise Bastide and Italian semiologist Paolo Fabbri proposed an intriguing solution: ray cats.

Imagine a cat bred to turn green when near radioactive material. That is, in essence, the ray cat solution.

“[Their] role as a detector of radiation should be anchored in cultural tradition by introducing a suitable name (eg, ‘ray cat’)” Bastide and Fabbri wrote at the time.

The idea has recently been revived. The Ray Cat Movement was established in 02015 to “insert ray cats into the cultural vocabulary.”

Alexander Rose, Executive Director at Long Now who has visited several of the proposed nuclear waste sites, suggests however that solutions like the ray cats only address part of the problem.

“Ray cats are cute, but the solution doesn’t promote a myth that can be passed down for generations,” he said. “The problem isn’t detection technology. The problem is how you create a myth.”

Rose said the best solution might be to not mark the waste sites at all.

“Imagine the seals on King Tut’s tomb,” Rose said. “Every single thing that was marked on the tomb are the same warnings we’re talking about with nuclear waste storage: markings that say you will get sick and that there will be a curse upon your family for generations. Those warnings virtually guaranteed that the tomb would be opened if found.”

“What if you didn’t mark the waste, and instead put it in a well engineered, hard to get to place that no one would go to unless they thought there was something there. The only reason they’d know something was there was if the storage was marked.”

Considering the relatively low number of casualties that could come from encountering nuclear waste in the far future, Rose suggests that likely the best way to reduce risk is avoid attention.

VI. A Perceived Abundance of Energy

San Onofre’s nuclear waste will sit in a newly-developed Umax dry-cask storage container system made of the most corrosion-resistant grade of stainless steel. It is, according to regulators, earthquake-ready.

At San Onofre, wood squares mark the spots where containers of spent fuel will be encased in concrete / via Jeff Gritchen, OC Register

Environmentalists are nonetheless concerned that the storage containers could crack, given the salty and moist environment of the beach. Others fear that an earthquake coupled with a tsunami cause a Fukushima-like meltdown on the West Coast.

“Dry cask storage is a proven technology that has been used for more than three decades in the United States, subject to review and licensing by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission,” said a spokeswoman for Edison, the company that runs San Onofre, in an interview with the San Diego Union Tribune.

A lawsuit is pending in the San Diego Supreme Court that challenges the California Coastal Commission’s 02015 permit for the site. A hearing is scheduled for March 02017. If the lawsuit is successful, the nuclear waste in San Onofre might have to move elsewhere sooner than anybody thought.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Energy in January 02017 started efforts to move nuclear waste to temporary storage sites in New Mexico and West Texas that could store the waste until a more long-term solution is devised. Donald Trump’s new Secretary of Energy, former Texas governor Rick Perry, is keen to see waste move to West Texas. Residents of the town of Andrews are split. Some see it as a boon for jobs. Others, as a surefire way to die on the job.

Regardless of how Andrews’ residents feel, San Onofre’s waste could soon be on the way.

Tom Palmisano, Chief Nuclear Officer for Edison, the company that runs San Onofre, expressed doubts and frustration in an interview with the Orange County Register:

There could be a plan, and a place, for this waste within the next 10 years, Palmisano said – but that would require congressional action, which in turn would likely require much prodding from the public.

“We are frustrated and, frankly, outraged by the federal government’s failure to perform,” he said. “I have fuel I can ship today, and throughout the next 15 years. Give me a ZIP code and I’ll get it there.”

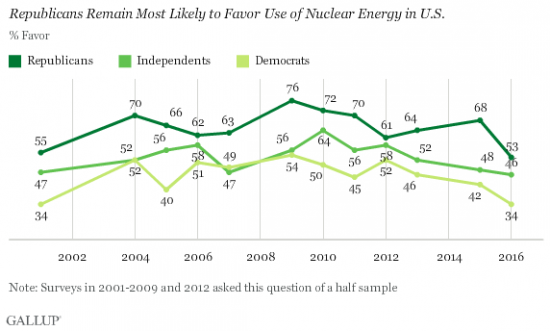

A prodding public might be in short supply. According to the latest Gallup poll, support for nuclear power in the United States has dipped to a fifteen-year low. For the first time since Gallup began asking the question in 01994, a majority of Americans (54%) oppose nuclear as an alternative energy source.

Support for nuclear energy in the United States / via Gallup

Gallup suggests the decline in support is prompted less by fears about safety after incidents like the 02011 Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown, and more by “energy prices and the perceived abundance of energy sources.” Gallup found that Americans historically only perceive a looming energy shortage when gas prices are high. Lower gas prices at the pump over the last few years have Americans feeling less worried about the nation’s energy situation than ever before.

Taking a longer view, the oil reserves fueling low gas prices will continue to dwindle. With the risks of climate change imminent, many in the nuclear industry argue that nuclear power would radically reduce CO2 levels and provide a cleaner, more efficient form of energy.

But if a widespread embrace of nuclear technology comes to pass, it will require more than a change in sentiment in the U.S. public about its energy future. It will require people embracing the long-term nature of dealing with nuclear waste, and ultimately, to trust future generations to continue to solve these issues.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe