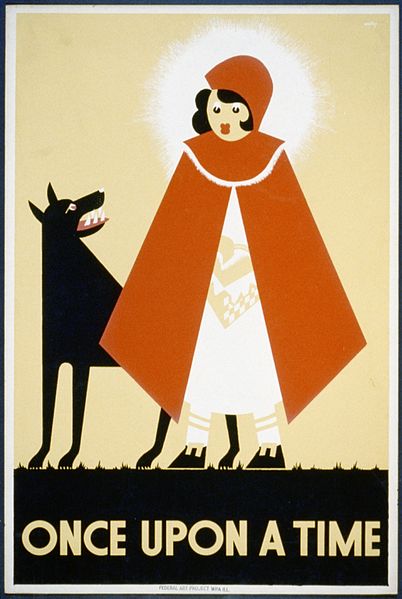

The Evolution of Little Red Riding Hood

We in the Western world are not the only ones who grow up with the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood.

Stories about young children who face off with a trickster wild animal are told around the world. In East Asia, for example, there is the tale of a tiger who masquerades as an old woman to lure her grandchildren into bed with him. And in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the evil beast is an ogre who ensnares a young girl by imitating the voice of her brother.

Oral folk tales like these change easily as they are told and retold through generations. They’re fluid, ever-morphing cultural artifacts – and as such, their history and cross-cultural relatedness can be difficult to trace. Nevertheless, an anthropologist at Durham University in the UK has recently shown that it can be done. Borrowing methods that are commonly used in biology to establish evolutionary relationships between species, an analysis conducted by Jamshid Tehrani reveals that these varying narratives are related to one another much like humans are to the Great Apes: they all, ultimately, descend from the same ancestor.

That ancestor, in this case, is a story called “The Wolf and the Kids:” an ancient folktale with European roots, in which a wolf pretends to be a mother goat in order to eat her babies. The Daily Mail quotes Tehrani:

My research cracks a long-standing mystery. The African tales turn out to be descended from The Wolf and the Kids but over time, they have evolved to become more like Little Red Riding Hood, which is also likely to be descended from The Wolf and the Kids. This exemplifies a process biologists call convergent evolution, in which species independently evolve similar adaptations. The fact that Little Red Riding Hood evolved twice from the same starting point suggests it holds a powerful appeal that attracts our imaginations.

Tehrani’s work also contradicts the long-held theory that both Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf And the Kids originated in East Asia – in fact, he shows, it was the other way around. “Specifically,” the anthropologist says, “the Chinese blended together Little Red Riding Hood, The Wolf and the Kids, and local folk tales to create a new, hybrid story.”

Fairy tales and other stories serve a purpose. They help us make sense of the world and of ourselves, and give us a way to transmit our knowledge and beliefs from generation to generation. As such, Tehrani’s study does more than show that societies around the world and across time have shared their stories with one another: it suggests a certain unity of human psychosocial experience. There must be, out in the world, some real or prospective experience that we are all faced with at some point or other – an experience in which we all seem to find ourselves supported by the narrative theme of young children confronted by a wily wolf.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe