The Digital Public Library of America

A digital library that makes published material available to anyone with an internet connection, free of charge: a realistic possibility, or a utopian fantasy?

Last April, a contributor to the MIT Technology review questioned whether it could be done: if Google Books had become mired in legal battles with US copyright law, would anyone else be able to figure out how to make published matter publicly available?

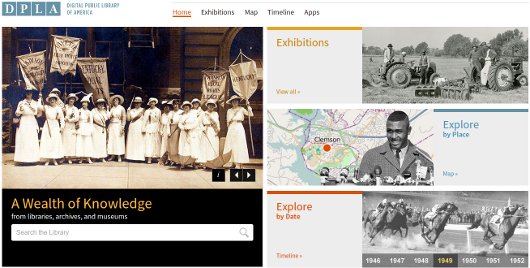

But this past week, the Digital Public Library of America celebrated its official launch at a library in Boston. As Harvard University librarian Robert Darnton explains, the Library is a nonprofit “project to make the holdings of America’s research libraries, archives, and museums available to all Americans – and eventually to everyone in the world – online and free of charge.”

Partnering with institutions such as the Smithsonian, the New York Public Library, and ARTstor, the Digital Public Library of America is not a database but a “distributed system of electronic content.” Rather than reinvent the wheel of digitization, it embraces what existing libraries and other organizations have already scanned in, and simply works to bring these resources together on a single, openly accessible, and nation-wide platform.

Unlike Google Books, the DPLA doesn’t hoover up institutions’ documents to be stored on its own servers. Its primary goal is to support coordinate scanning efforts by each of its partner institutions, and to act as a central search engine and metadata repository. Most of these libraries and museums have been slowly scanning and cataloguing their collections for years; the DPLA helps make those materials aggregatable and interoperable. (theverge.com)

In efforts to contribute to a truly universal spread of knowledge, the Digital Public Library of America offers a user-friendly interface and a searchable collection of materials under a Creative Commons license: “We are really fighting for a maximally usable and transferrable knowledge base,” says executive director Dan Cohen. Though the Library will – for the moment – refrain from offering anything that is currently under US copyright protection, part of its mission is to explore alternatives to existing copyright laws. As The Verge explains,

[Cohen] wants to create a platform where academic scholarship, whether in journals or monographs, can be disseminated and preserved in open formats for current and future generations. He wants to find ways for public libraries to engage in collective action with book publishers to make e-books as available as possible to US citizens. He wants the DPLA to explore alternative approaches to copyright that preserve authors’ and publishers’ chief profit window but also maximizing a work’s circulation, including the “library license” that would allow public, noncommercial entities (like the DPLA) to have digital access to certain works in copyright after five years, or Knowledge Unlatched, a consortium that purchases in-copyright books for open access. The DPLA also wants to work directly with authors to donate their books to the commons.

Princeton philosopher Peter Singer writes that “scholars have long dreamed of a universal library containing everything that has ever been written.” He calls this a “Library of Utopia” – but agrees with the Digital Public Library of America that a utopia is more than idle fantasy. It is an idea worth striving for; perhaps even a moral imperative.

“If we can put a man on the moon and sequence the human genome, we should be able to devise something close to a universal digital public library. At that point, we will face another moral imperative, one that will be even more difficult to fulfill: expanding internet access beyond the less than 30% of the world’s population that currently has it.”

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe