Optimism in the Anthropocene

On sci-fi and futurism blog io9, editor Annalee Newitz made the case recently for what she calls geological optimism:

My hope for the future comes from geology, and a belief that one day we will invent machines that are environmental rather than technological.

Newitz argues that thinking about change and growth in primarily technological terms is bound to leave us blinkered and disappointed. In the same vein, Professor of Economics Jonathan Dawson hopes for a similarly expanded awareness to reshape economic thought in a column for The Guardian:

Ecology offers the insight that the economy is best understood as a complex adaptive system, more a garden to be lovingly observed and tended than a machine to be regulated by mathematically calculable formulae.

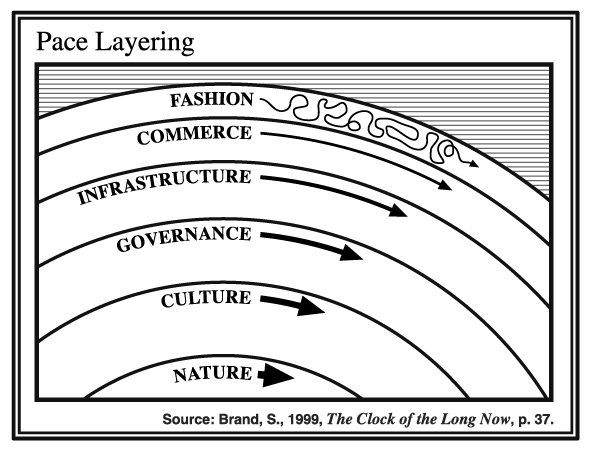

Technology is but one epiphenomenon of the natural world and it sits nested within larger, slower societal, biological and geological processes. In the concept of pace layering, inspired by the architectural idea of shearing layers, technology is primarily a commerce and infrastructure level phenomenon, but increasingly has effects on even the deepest, slowest layers.

It is largely through technology that humans have (more or less by accident) become drivers of the planetary system. As we develop agency within the deeper, slower layers of our world’s processes, we must better understand those systems and better incorporate their operating principles into our own self-governance, else we’ll drive into a ditch.

The flaws in techno-optimism and classical economic thinking Newitz and Dawson decry represent the clumsy influence of the commerce and infrastructure layers on the nature and culture layers. Both authors propose that we instead allow our increasingly refined understandings of nature and culture to inform decisions in the faster layers.

A real-world example can be seen in National Geographic’s recent cover story on sea-level rise. Surveying how communities around the world are adapting to and preparing for redefined coastlines, author Tim Folger describes a Dutch creation known as the zandmotor. Where sea-level rise has lead to beach erosion, flooding is a danger and traditional renourishment methods are expensive:

The typical solution would be to dredge sand offshore and dump it directly on the eroding beaches—and then repeat the process year after year as the sand washes away. Mulder and his colleagues recommended that the provincial government try a different strategy: a single gargantuan dredging operation to create the sandy peninsula we’re walking on—a hook-shaped stretch of beach the size of 250 football fields. If the scheme works, over the next 20 years the wind, waves, and tides will spread its sand 15 miles up and down the coast. The combination of wind, waves, tides, and sand is the zandmotor.

In 02009, author and forecaster Karl Schroeder sketched a near-future scenario (already both dated and prescient) that also serves to illustrate a type of geological optimism. He calls his scenario “re-wilding” and in one example describes a wetland that naturally filters the water for a city. Sufficiently monitored and understood, its value to the human economy – and individual consumers – can be precisely calculated and billed. Imaging this possibility where today we’d more likely build a man-made filtration plant, he explains, “We’ve introduced the idea of negotiating with a self-willed world.”

While next century’s historians may call our time the Information Age, the next millennium’s historians will likely be more interested in the dawn the of Anthropocene epoch. As a cynical saying goes, “Employees tend to rise to their level of incompetence.” And as the scale of humanity’s influence on the natural world has expanded, it’s hard not to worry that we’re promoting ourselves beyond our capabilities. But the zandmotor and the possibility of re-wilding can be sources of hope, signs that our understandings of different pace layers are increasing and increasingly allowing us to grow into our role, and evidence that geological optimism and the Anthropocene aren’t mutually exclusive.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe