Lynn Rothschild Takes the Long View

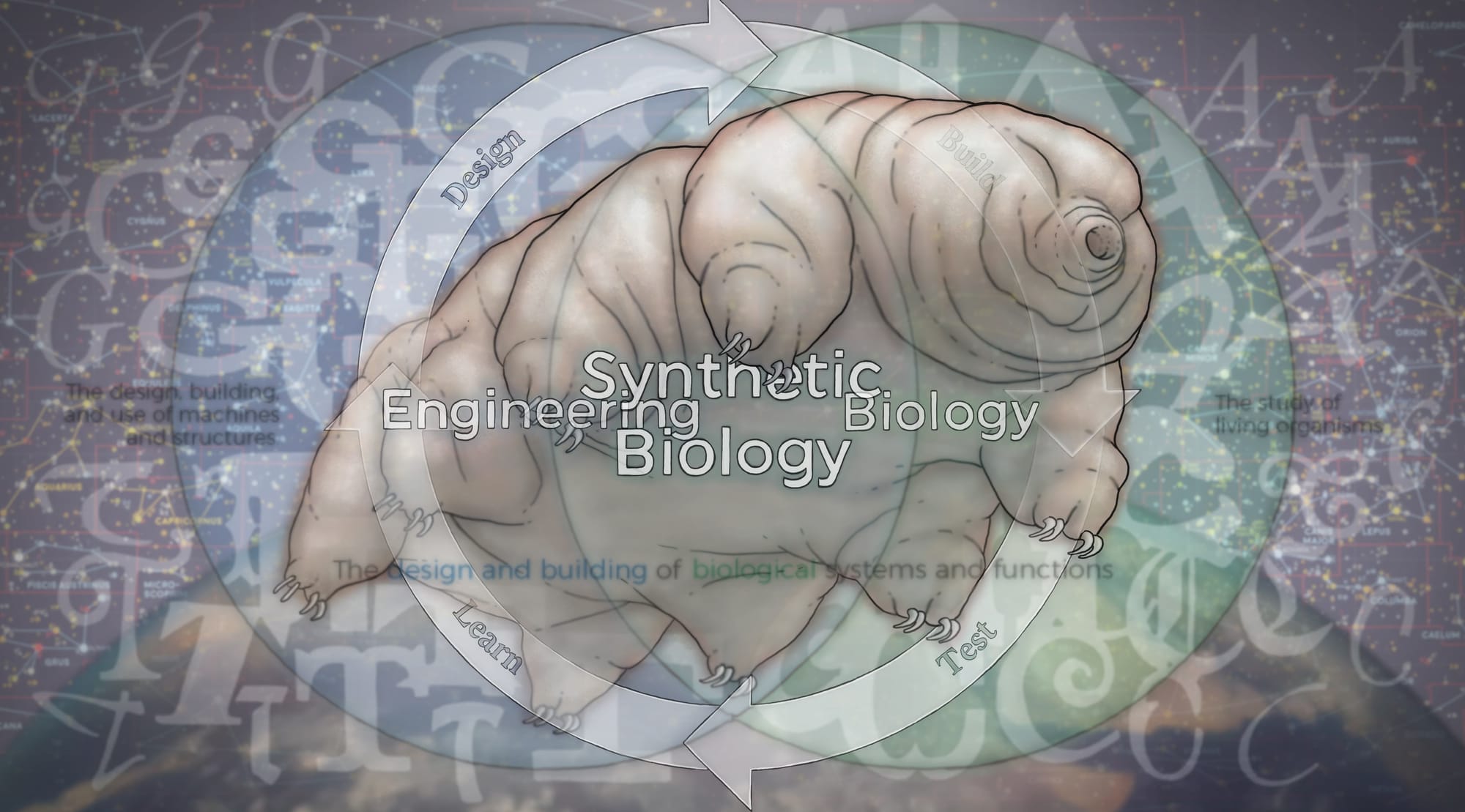

The NASA astrobiologist speaks with Long Now about synthetic life, evolutionary time, and why she believes humans will find a way to keep the lights on.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your lab has made some mind-boggling creations: mycelium on the moon, biological glue, DNA wire. How did you get here?

I'm an evolutionary biologist by training and by love, particularly protozoan algae. I came to NASA to search for life in the universe. To do that, you have to understand where life comes from and where it might be going and what else might be out there.

About 20 years ago, the then-director of the NASA Ames Research Center became interested in synthetic biology and what life could do as a technology for space. He turned to me and said, basically, Here’s a grad student, start a program in it. That’s taken over my life for the past two decades.

Your timeline of knowledge goes in both directions: you have to understand the past very deeply in order to understand how it can be applied in the future. In many fields that’s more philosophical, but it’s very, very applied in yours.

It’s very applied, but interesting you bring up “philosophical” because every now and again, I stop and say: We’re throwing out these numbers like 4 billion years or even 400,000 or even 4,000, and that is really beyond what I think humans can conceive of. We’re in that 100-year-time span. I had a grandmother who almost made it to 101. 100-year chunks we can understand, but much more than that, we’re just spouting numbers. I don’t think we as humans are able to get that kind of gut feeling. I can know what four billion years is rationally, but that’s different from having a gut feeling for what four billion years is.

Can you get closer to that gut feeling with practice?

Yes and no, but I think it’s also in some ways equally difficult to conceive of fractional periods of time. I was invited to speak at Caltech about 10 or 15 years ago by the International Horological Society. The first session was looking at time from the perspective of different sciences. I was given the remit to talk about time and what it meant to a biologist. And it was fun because it pushed me in areas that I enjoy but don’t normally have an excuse to think about. And once I started thinking about it, I realized that life is extremely unusual in that we deal with time scales that go from the femtoseconds in something like photosynthesis or making ATP in your body, all the way to billions of years.

Did you find that you had a lot in common with the horologists?

No, but I had a great time. I recall the last talk being fascinating. It talked about how at this point, we can create timepieces that are accurate within a second of the age of the universe, the universe being 13.6 billion years old. And you ask: “Why on Earth would you need something like that? I’m lucky if I’m within one minute of the Zoom.” And the answer is very simple: GPS. You don’t have that precision, you can’t have GPS.

What’s the most surprising way history has repeated itself in synthetic and evolutionary biology?

I see a certain amount repeating at work simply because a lot of scientists and engineers are focused on the future: what is the latest paper, and can they jump ahead of the field? They don’t tend to look back. In fact, I remember in grad school looking up an interesting paper on the evolution of metabolic pathways that was published in 01946. We used to go to libraries in those days, and a professor came over to me and said: “Why are you in this section? This is the old stuff.” And it’s because it was important for what I do. We have a tendency to forget the old stuff. I can’t tell you how many times I still find that Darwin thought of it first.

Sometimes we’re reinventing things in my own parochial field of looking for life in the solar system and beyond. I happen to be someone who thinks that the Viking missions to Mars in 01975 were very clever, particularly for the science they had at the time. The scientists, many of them Nobel Prize winners, designed them as agnostic experiments that did not depend on life being a certain way. Some of my colleagues are designing experiments today that are much more specific, with much lower chances of working out compared to the Viking missions.

We can learn a lot from the history and philosophy of science. In 01859, 10 years after Origin of Species, Huxley said it was no fun anymore because he and Darwin had won the argument. That to me, is a big question: How, in a decade, were you able to change the overwhelming consensus of the scientific community to a completely different view? How does an idea get adopted?

If you could choose a single artifact to represent our time in the far-flung future in an archive, what would it be?

Pristine organisms. Some people worry about genetically modified food, but there’s virtually nothing we eat that we haven’t genetically modified. Corn used to be teosinte. These giant tomatoes, this is not the ancestral form. Not to mention cows and sheep and everything else.

Maybe the greatest gift we could give to the future is a sort of genetic seed bank of what’s available today that’s as pristine as possible. It’s already not pristine; there is no real “this is what Earth is supposed to be like,” because you’re taking a snapshot. People say: “Oh, we have to have it back to the way it was. Well, that’s picking and choosing. Do you mean a hundred years ago? Well that wasn’t the way it was 500 years before that, or a thousand. Is it when you have no organisms on the Earth? Is it dinosaurs? Quite honestly, the pristine condition of the Earth was not having life at all.

While you can’t really say what’s pristine, I do think being able to get some kind of snapshot of what the genetic inventory is on Earth today could be the greatest artifact we could leave.

What’s a global challenge today that you think will be solved over the long term?

I’m essentially an optimist, so I think that in the near term — and when I say near term, I’m talking about a billion years — we may figure out a technological solution for saving the Earth from being destroyed by the dying sun. Maybe we’ll cool it down, maybe we’ll reset it, throw in some new molecules to reverse its warming. Failing that, we may be able to move the orbit of the Earth.

What if, instead of getting people off the Earth — a logistical and ethical nightmare, who do you send? — you just turn the Earth into a spaceship and start slowly moving it out as the sun gets hotter? Maybe you stop by Mars for some water along the way, pick up some stuff from asteroids, some organics from Titan, fill up your gas tanks. You’re moving out to where it stays habitable when the sun does warm, and we have enough energy from other means on the Earth. We hang out there until the time’s right to move back in a little bit. Once the sun becomes a dwarf star, it’ll remain that way until the universe ends.

I truly believe we’ll have that kind of technology. People ask: How are you actually going to do it? My response is, I can’t solve all of the problems of mankind, but I think we’ll be able to do that kind of thing in a hundred or 200 years.

We are hardwired for survival. No human is going to be the one to turn off the lights and say, “Well, that was a good run. Bye.” We’re going to do everything we can to survive.

I love the idea of the planet being the ship itself. We just move the beach chairs up when the tide comes in and then move them back when the sun becomes a red dwarf.

Exactly. I’m not terribly worried about aliens coming to attack us or anything like that. It’s so difficult to travel. If all life is based on organic matter, other aliens are going to have exactly the same problem as us. They would send robotic surrogates, and even then you’ve got to worry about radiation shielding and all that sort of stuff.

I can’t say radiation shielding keeps me up at night. Should it?

Yes! It keeps me up at night.

What’s one event from the past you would’ve loved to witness?

The origin of life, because then we would understand everything.

I suspect that there were a lot of life form efforts and that one of them took over. It may not have even been the best. Sort of like how Windows has become the prevalent operating system. (I happen to be heavily into Mac operating systems — life is too short for Windows!)

In the same way, maybe there was another operating system for life, and this is just the one that took off. Like humans: one species, one approach survived. Now, how long did that take? People say it must have taken hundreds of millions of years, because they figure it was so hard. But we have no idea. It could have been a three-day weekend.

I suspect at some point there was a buildup of chemicals in the right conditions, and then there were enough little vesicles that had things in it, and some of them, like a terrarium, were good enough and they were able to reproduce, and for whatever reason, they were in the right place at the right time.

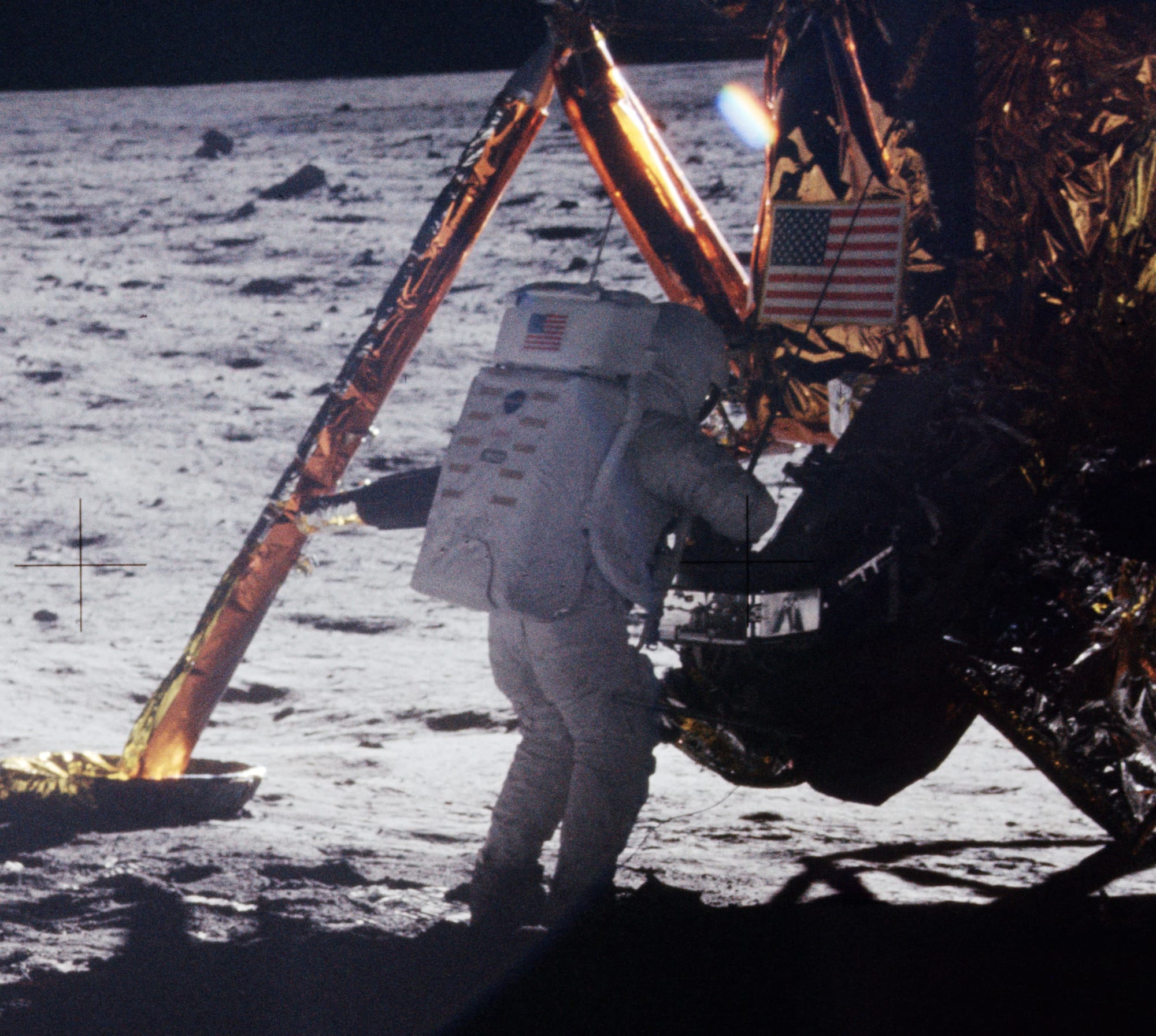

I love how far back in time your answer goes. I think my answer would have been early space travel or maybe to see Neil Armstrong take those first steps on the moon.

See, that’s the difference between the two of us: I’m old enough that I did see it. I was 12 years old at a summer camp in Maine, and I stayed up all night. It was amazing.

Years later, I was at a NASA meeting and I knew Neil Armstrong was going to be there. Just the idea of being in the same room with him was incredible. But when the moment came, I had no idea what to do. I just froze. What do you do in a situation like that? What would you have done?

Probably babbled something incoherent.

Well, it turns out the thing that I said was actually what I watched other people do, but it just came out of my mouth. I just looked at him and said: Can I shake your hand?

Wow.

I have washed my hands since then.

What a great moment.

I've heard people say that the only human name that will be remembered in 1,000 years is Neil Armstrong. I hope that’s not true.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe