Human Self-Interest and the Problem of Solving Long-Term Issues

We are a selfish, short-sighted lot. As many a game theory experiment has shown, we simply aren’t as motivated by the promise of collective future benefits as we are by the gratification of instant private rewards.

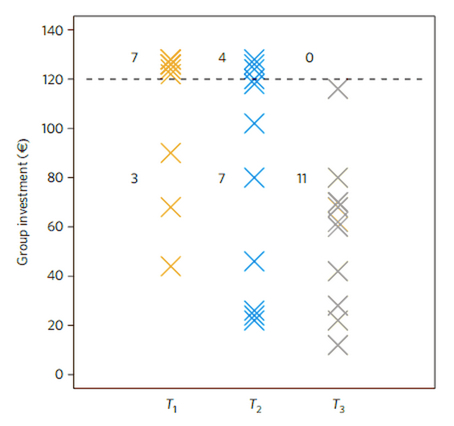

A group of researchers based at NYU now argues that this kind of self-interest can throw up significant hurdles to the process of solving long-term, multi-generational problems like climate change. As reported in the October issue of Nature Climate Change, The team conducted a study that measured participants’ willingness to invest personal resources into a group effort that would lead to rewards in the future: each subject was given €40, and was then asked to deposit €0, €2, or €4 into a collective “climate account” that would fund an environmental awareness advertisement. If each participant deposited enough for the account to reach a total of €120, all would receive an additional €45.

However, the reward of cooperation, the €45 endowment per group member for meeting the €120 target, was distributed on three different time horizons. In one treatment (T1), the €45 cash endowment was paid the next day; in the second treatment (T2), the €45 cash endowment was paid 7 weeks later; in the third treatment (T3), the €45 endowment was invested in planting oak trees that would sequester carbon (as well as provide habitat and greenery) and therefore provide the greatest benefit to future generations, although in a currency different to the monetary endowments offered in T1 and T2.

Just as the scholars hypothesized, participants’ willingness to invest was highest in the T1 scenario, and lowest for T3. In other words: the further a reward lies in the future – and the less likely the individual therefore is to benefit from it himself – the less motivated he is to give his personal resources up for the greater good. The research group concludes:

The results show the power of intergenerational discounting to undermine cooperation …. Immediate monetary rewards seem to matter most. Applying our results to international climate change negotiations paints a sobering picture. Owing to intergenerational discounting, cooperation will be greatly undermined if, as in our setting, short-term gains can arise only from defection. This suggests the necessity of introducing powerful short-term incentives to cooperate, such as punishment, reward or reputation, in experimental research as well as in international endeavours to mitigate climate change.

The article explains that immediate and delayed rewards trigger entirely different parts of the human brain, suggesting that long-term and short-term strategizing involve divergent cognitive processes. It seems, then, that our best chance of fostering a sense of accountability for the future may be to create scenarios in which both parts of the brain are stimulated simultaneously: by coupling the incentive of long-term rewards with that of very short-term consequences.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe