How Long is Now?

Most of us are content to live in a world where time is simply what a clock reads. Interdisciplinary artist Alicia Eggert is not.

The most commonly-used noun in the English language is, according to the Oxford English Corpus, time. Its frequency is partly due to its multiplicity of meanings, and partly due to its use in common phrases. Above all, “time” is ubiquitous because what it refers to dictates all aspects of human life, from the hour we rise to the hour we sleep and most everything in between.

But what is time? The irony, of course, is that it’s hard to say. Trying to pin down its meaning using words can oftentimes feel like grasping at a wriggling fish. The 4th century Christian theologian Saint Augustine sums up the dilemma well:

But what in speaking do we refer to more familiarly and knowingly than time? And certainly we understand when we speak of it; we understand also when we hear it spoken of by another. What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not.

Most of us are content to live in a world where time is simply what a clock reads. The interdisciplinary artist Alicia Eggert is not. Through co-opting clocks and forms of commercial signage (billboards, neon signs, inflatable nylon of the kind that animates the air dancers in the parking lots of auto dealerships), Eggert makes conceptual art that invites us to experience the dimensions of time through the language we use to talk about it.

Her art draws on theories of time from physics and philosophy, like the inseparability of time and space and the difference between being and becoming. She expresses these oftentimes complex ideas through simple words and phrases we make use of in our everyday lives, thereby making them tangible and relatable.

Take the words “now” and “then.” In its most narrow sense, “now” means this moment. But it can be broadened to refer to today, this year, this century, et cetera. “Then” can mean both the past and the future. Eggert’s “Between Now and Then” explores how these two time relationships depend on one another. The words “NOW” and “THEN” are inflatable sculptures of nylon connected to the same air source. The fan is reversible, so one word literally sucks the air out of the other.

In the philosophy of time, those who ascribe to eternalism believe all time is equally real, and that the past, present, and future all exist simultaneously. In “All the Time,” Eggert gives this philosophical approach material form by altering a clock to give it twelve functioning hour hands.

On the roof of a convenience store in Philadelphia is the permanent installation “All the Light You See.” The neon sign alternates between two statements: “All the light you see is from the past” and “All you see is past.” It also turns off completely for a brief time.

“It speaks to the fact that light takes time to travel, so by the time it reaches your eyes, everything you are seeing is technically already in the past,” Eggert writes in a description of the artwork. “Light from the moon left its surface 1.5 seconds ago; sunlight travels for 8 minutes and 19 seconds before it touches your skin. The farther out into space we look, the farther back in time we can see.”

“There are different levels to my work,” Eggert tells me. “At the surface level, it’s extremely accessible and understandable by most people. But then you can peel away the different layers, think more deeply about what it is actually saying, and have the opportunity to ask those big existential questions or have those reflective, introspective moments.”

Eggert lives in Denton, Texas, where she is professor of sculpture and studio art at the University of North Texas. Her work has been exhibited at cultural institutions throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia.

Both her interest in time and her focus on making her art accessible come from a surprising source: evangelical Christianity.

“I was raised in an environment where all these ideas about eternity, the afterlife, and why we’re here were planted in me from an early age,” she says. “That’s kind of all you talk about at church.”

She was born into a religious family in Camden, New Jersey, in 01981. She attended church — where her father was a Pentecostal minister — twice every Sunday, and again on Wednesdays.

“In different religions, there are different levels of importance placed on whether or not people actually understand or feel moved by the scripture or the message,” she says. “Unlike in a Catholic church that speaks Latin during the service, in the Pentecostal church I grew up in, the goal was to bring people into the fold and make sure everyone felt welcome and understood what was going on: ‘We’re talking about big, crazy, things, but we’re going to put it in this package that you can swallow.’ I think that was somehow embedded in me.”

While Eggert was influenced by the medium, she was more skeptical of the message. In the Christian worldview she was taught, life on Earth was suffering. Deliverance came only in the eternal hereafter.

“Something about that just kind of struck me as really wrong,” she says. “We have this one life to live, and the attitude was: ‘I can’t wait until it’s over, so I can get to heaven.’”

“I started thinking, kind of subconsciously, not really consciously, about the detrimental effects that ‘small now’ attitude had on the world and almost everything, in a way I can see much more clearly as an adult,” she says. “If you feel like life is all about suffering, and then after death is when you get to be in heaven, that permeates all of your actions. It permeates the attitudes that we take towards the planet, to other animals, and species: ‘All of this is just temporary anyways, so we don’t necessarily have to conserve it.’”

By high school, Eggert knew she no longer believed in Christianity. (She would eventually “come out” to her parents as an atheist in college). She started to focus more and more on the idea that, as she puts it, “the time we have is the only time we have.” She started reading philosophy and picked up a “not very serious” interest in Buddhism to explore the implications of that worldview: if we only have one life to live, what, then, does “time” mean? What does “eternity” mean?

In her last semester at Drexel University, where she was studying interior design, she discovered that conceptual art offered a gateway to explore these questions.

“All of a sudden, I understood that I could make art that was driven by an idea instead of an image,” she says. “And there are so many different ways you can bring an idea into existence, from just simply communicating it with text, to using all kinds of different sculptural materials, processes, and forms.”

While pursuing a Master in Fine Arts in sculpture at Alfred University, she began to merge her philosophical interest in time with her artistic practice.

In an early piece from 02008 titled “The Length of Now,” Eggert soaked a yarn of red string in water and froze it into the shape of the word “now.” She then hung it on a wall and filmed it while it melted. (“Now,” in that artwork, turned out to be two minutes and forty-three seconds long).

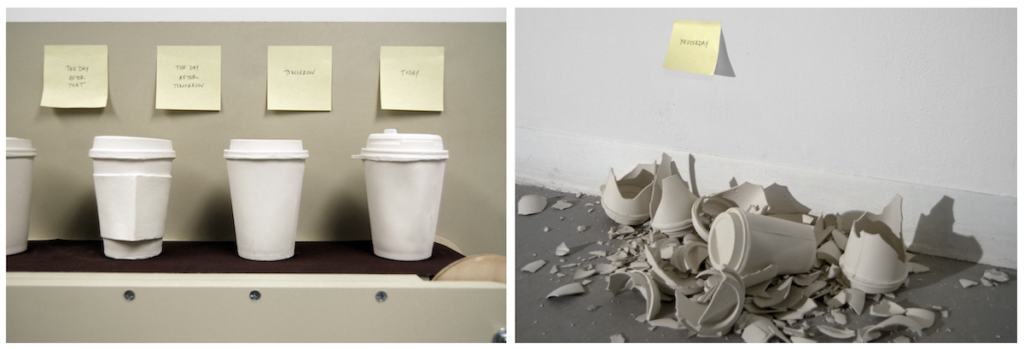

“Coffee Cup Conveyor Belt Calendar” reimagined the daily ritual of having a cup of coffee on the way to work each morning as units of time, with each cup representing a day. The porcelain cups traveled slowly across a conveyor belt past post-it notes that read “Today,” “Tomorrow,” “The day after that,” “The day after that.” Every twenty-four hours, a cup fell off the end of the conveyor belt, shattering into a pile. Above the pile of shattered cups was a post-it note labeled “Yesterday.” Because the cups were made of unfired porcelain, the shards could be reconstituted into slip and remade into cups that started the cycle anew.

“That was the first time I ever made a kinetic sculpture that incorporated time and movement into the work,” Eggert says. “It was also the first time that I really started to think about cyclical versus linear time. That led me to start reading about time as it’s thought about in physics.”

Eggert considers “Between Now and Then” to be a breakthrough piece. It was her first experiment with signage, and could be found mounted on the wall of the hallway outside of her studio. On one side of the sign was the word “NOW.” On the other, the word “THEN.” Those who walked by could easily mistake it for a bathroom sign. Eggert saw it as “a blade that slices through a person’s path, dividing time and space.”

“That was when I really started to focus primarily on time with my work, and giving language a physical form,” Eggert says. “For a little while, I couldn’t figure out how those two things were related, but now that seems to be the combination of what I do primarily.”

A clock tells you what time it is. Eggert’s art asks you what time is. She doesn’t provide answers so much as present a constellation of possibilities.

“I’m fascinated by all the different ways people think about time,” she says. “Some say it exists. Some say it doesn’t exist. Some say the present moment is all there is, others say discrete moments all stack up like the individual pages of a book, and that’s why we have this illusion that time is linear. There’s no way to prove that any of these ways of thinking about time is actually right. There’s probably little bits and pieces from all the different explanations that maybe form an answer. I don’t know. I just want to know as many of the explanations people have thought of as possible.”

In 02015, she came across a way of thinking about time that deeply resonated with her. It would inspire two artworks, including a light sculpture, “This Present Moment,” that was recently acquired by the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, the premier museum of American craft and decorative arts.

It was called the Long Now.

In 01999, Gary Snyder, the Zen poet, sent an epigram to Stewart Brand, the environmentalist and cyberculture pioneer best known for founding and editing the Whole Earth Catalog:

This present moment

That lives on to become

Long ago.

Snyder’s poem alluded to how the present becomes past. Brand responded with a riff of his own, on how the future becomes present:

This present moment

Used to be

The unimaginable future.

At the time, Brand was at work completing The Clock of the Long Now, a book of essays that introduced readers to the ideas behind the 10,000 Year Clock and The Long Now Foundation, the nonprofit organization he co-founded with Brian Eno and Danny Hillis in 01996.

The book was a clarion call for engaging in long-term thinking and taking long-term responsibility to counterbalance civilization’s “pathologically short attention span.” Brand argued that by enlarging our sense of “now” to include both the last 10,000 years (“the size of civilization thus far”) and the next 10,000 years, humanity could transcend short-term thinking and engage the challenges of the present moment with the long view in mind. This 20,000-year frame of reference is known as the Long Now, a term coined by Brian Eno.

Brand included his exchange with Snyder as the book’s closer. (Snyder would ultimately include his contribution in a 02016 collection of poetry, This Present Moment).

Brand’s epigram became one of the most shared selections from a book full of “quotable quotes,” regularly appearing in motivational tweets and the slides of keynote presentations. He always makes a point of crediting Snyder when the quote is attributed to him alone. I asked Brand recently whether this was simply a matter of giving credit where credit was due, or if he felt there was a deeper connection between the two poems that was lost when viewed in isolation. (Another famous Brand quip, “Information wants to be free,” is often shared without the crucial second part: “Information also wants to be expensive.”)

“Both credit and connection help the quote,” Brand told me. “Gary lends gravitas with the credit. Also it’s a sequence, which he started. The two riffs book-end time, backward and forward, the way Long Now tries to.”

“It’s a conversation,” Brand said. “Nearly all art is, not always so overtly.”

In 02018, Eggert added her voice to the conversation. She’d read The Clock of The Long Now three years earlier, and found the concept of the Long Now a compelling corrective to the detrimental effects of the small now she saw in religion. She was particularly struck by Brand’s “This present moment…” epigram.

“I’m on a constant hunt for literature to read that will be another star in that constellation of my understanding of time,” she says. “My process as an artist is, as I’m reading these books, I always keep a sketchbook nearby. If there’s ever a quote that jumps out at me, I write it down. Then, when I’m brainstorming for new work for an exhibition, I’ll oftentimes go back through my notebooks and look at all the quotes that I’ve written down. I don’t know how or why I ended up choosing Brand’s words at that particular time, but I started realizing that they were saying exactly what I was feeling at that moment to be true or important.”

When Eggert asked Brand on Twitter whether she could have permission to turn the quote into a neon sculpture, his response was typical: “Sure!” (The footer of Brand’s personal website reads: “Please don’t ask for permission to borrow my stuff: just do it”).

“This Present Moment,” which initially went on display at the Galeria Fernando Santos in Porto, Portugal in 02019 and will debut at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in 02022, is a neon pink sign that is twelve feet tall and fifteen feet wide. It cycles through two statements. First: “This present / moment / used to be / the unimaginable / future.” Then, after a few seconds, the words “present” and “unimaginable” blink off, leaving: “This / moment / used to be / the / future.” And then the sign turns off. After a beat, the cycle repeats.

“This Present Moment” is more than Brand’s epigram rendered as a sign. By adding the element of time to how viewers experience the message, Eggert has made Brand’s words immediate, dynamic and personal.

At first glance, the piece conveys a deceptively simple truth: from the perspective of the past, this moment — as in, right now, as you read my words, and take in an animation of that sign — was once the future. But as time passes, questions arise: how long is a moment? Is it the interval between the sign turning off, and turning back on again? When does “now” end? When does “the future” begin?

It all depends, of course, on your perspective. The future might be ten seconds from now if that’s when your next meeting starts; next quarter, if you’re a businessperson; next election, if you’re a politician; an illusion, if you’re a Buddhist. Your sense of now might be impossibly brief, if you’re stressed, or apparently endless, if you’re mindful. It all depends on what you’re willing to consider, and what you’re willing to pay attention to.

The longer you pay attention to “This Present Moment,” the more meaningful it becomes.

“You could obviously zoom in on this present moment as being right now,” Eggert tells me. “Or you could zoom out on this present moment as being much longer. The way the sign flashes is a reminder of both of those things. When it turns off completely for a couple of seconds, and then starts to cycle back through, you’re reminded of that really short now. But the actual words suggest a much longer now as well.”

Perhaps, staring at that sign, you begin to realize that these two statements about time are always true for any human being who contemplates them. They were true for your ancestors. What was their present moment like? They’ll be true for your descendants. What unimaginable future awaits them?

“In our everyday lives, we’re inclined to think in short terms and see the present moment as small and narrow,” Eggert says. “But the same laws of nature that formed the rocks beneath our feet millions of years in the past are still in effect and in progress right now. And it seems as though our collective future might depend on our capacity to conceive of a ‘present moment’ that is much longer and wider — one that our limited field of view cannot contain.”

Such mental time travel is an exercise in empathy. The power of “This Present Moment,” like so much of Eggert’s artwork, is that it’s simple enough, and accessible enough, to make that exercise feel as intuitive as looking at a clock to check the time.

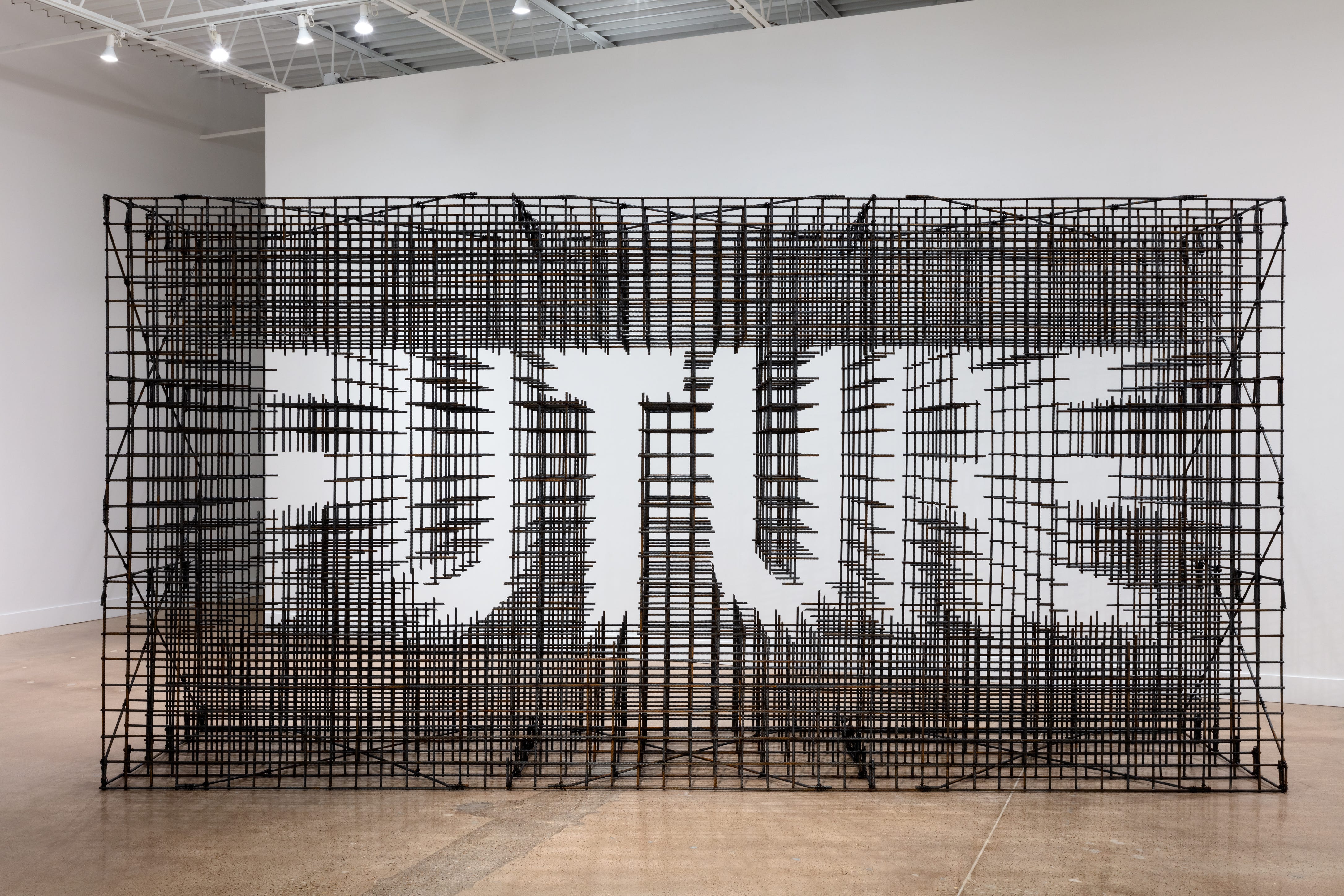

Eggert’s solo exhibition, “Conditions of Possibility,” opened at the Liliana Bloch Gallery in Dallas, Texas, in April 02021. A majority of the gallery space is occupied by her latest artwork, “The Unimaginable Future.”

A companion piece to “This Present Moment,” “The Unimaginable Future” consists of six layers of steel rebar with the word “FUTURE” occupying the negative space. Mounted on a nearby wall are three small kinetic structures that use clock hands to spell the word “NOW” at different speeds. The Long Now (represented by the steel “Future” sculpture) and the Short Now (represented by the three kinetic “Now” sculptures) coexist in the same moment.

The exhibition reflects Eggert’s conviction that when we engage with art that explores language and time — what she calls “the powerful but invisible forces that shape our reality” — we might wonder not only about what is real, but what is possible.

“Art provides us with opportunities to think deeply and meaningfully about what we value as individuals and as a society,” Eggert says. “Art gives us new ways of telling the same stories — ways that are continually more compelling, more emotive, more relatable and more experiential. Those experiences create new ways of understanding the world and the role we play in it. Art is a condition of possibility for imagining otherwise unimaginable futures.”

In a May 02021 Long Now talk, Sean Carroll, a physicist whose writings on time have strongly influenced Eggert’s work, spoke about how this capacity to imagine unimaginable futures is what makes human life meaningful.

As an example, he pointed to Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia, a modernist cathedral designed by Antoni Gaudi. Construction began in 01883, and Gaudi harbored no illusions that it would be completed by the time of his death, which occurred in 01926. It remains under construction to this day.

“The point is not that Gaudi thought that he would be a ghostly persistence over time that would be looking down on the cathedral and admiring it,” Carroll said. “He gained pleasure right at that moment from the prospect of the future. And that’s something that we humans have the ability to do. The conditions of our selves, right now, depend on our visions of the past and the future, as well as our conditions here in the present.”

Carroll went on to say:

We are temporary little bits of complex structure in the universe that are part of the overall increase of entropy over time. That means we are ephemeral. We’re not going to last forever. That’s the bad news. We’re not going to last for 10 to the 10 to the 10 years. We have a lifespan. We have an expiration date. But it also means we are interesting. We are the interesting part of the universe. Part of this complexity is our ability to think about and model ourselves and the rest of the universe to do what psychologists call mental time travel, to imagine ourselves not just in different places, but at different times. It’s that ability, that imagination, that flow through time, that makes us what we are as human beings.

It is all too easy to forget that we have this capacity to imagine unimaginable futures. It is all too easy to forget that time can mean more than the narrow concerns of the here-and-now or the hoped-for salvation of a timeless eternal then.

The art of Alicia Eggert helps us remember.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe