Generational Theater

Brian Eno emailed this note to the Long Now list:

Yesterday I had the good fortune to find myself in Oberammergau, in Upper Bavaria.

In the early seventeenth century, as plague raced across Europe, the people of this small town made a deal with God: spare us and we’ll perform a Passion play every ten years. All of us. The whole town.

True to their word, they’ve done this every decade since. The first performance was in 1634, and ever since it’s been at the turn of the decade. It’s a startling event, because everyone in the town really is involved. All the actors, the musicians, the technical staff, the director, the costumiers, the carpenters, the singers, the stagehands, the press agents, the bartenders, the ushers – are local people. In normal life they’re the hairdresser, the postman, the dentist, the notary, the teacher, the plumber, the bus driver.

What I went to last night was not the full-blown Passion play – that won’t happen until 2010 (they’re working on it now). I attended instead a play called JEREMIAS, written by the Jewish pacifist Stefan Zweig in 1933, which featured a relatively modest cast of 500, ranging in age from 3 to 80. The criterion for being in a play is that you should be born in Oberammergau or have lived there for 20 years. The current director is Christian Stückl, a local man who directed his first Passion at the tender age of 28 (making him the youngest director in the long history of the play). Stückl told us that, in the 2000 Passion, a group of Muslim inhabitants of the town asked if they could be included: they’d by that time fulfilled the 20 year residency criterion. After enormous discussion during which the Muslim folk elucidated the parallels between the Koran and the Bible, they were included.

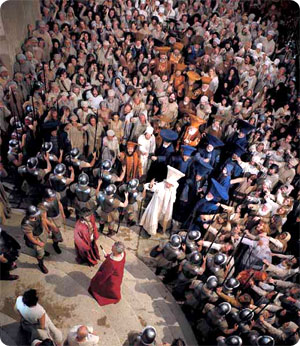

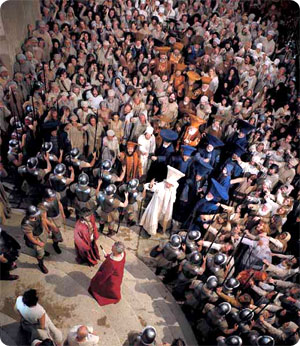

I won’t attempt a description of the content: my German is so rudimentary that I understood very little of what was going on. It was 3 hours long, but it didn’t matter: I was intrigued.There were at times several hundred people on the huge open-air stage (the audience sit inside, under cover, but the stage area is open to the sky, the elements and the changing light of evening): there was fire, rain, camels, sheep and horses, a 50 piece orchestra of local players and a 100 person choir of local singers…. all to a totally professional standard. There was nothing ‘local’ about the quality of any of the performances.

Luckily I’d brought along a little monocular, and that proved invaluable. I was intrigued by the faces – normal faces, normal children (picking their noses, being distracted), not ‘actory’ types. I kept returning to this thought: what would it do to a community to have a tradition as long and as defining as that, to know from an early age that you were, probably throughout your life, going to be woven into this incredibly rich tapestry of time, spirituality, art and craft? What would it be like to be a child growing up there, to watch your parents and grandparents learning their lines and practising their parts and building the sets and making the clothes? It must be so rich, such a powerful social binder and foundation.

Oh – I suddenly realised. It would be like tribal life. For isn’t this exactly what growing up in Bali or Mali, with their long traditions of folk art, must be like?

I tried to discover whether there had been any sociological studies of Oberammergau, to see whether this unique (in Europe anyway) situation produced any measurable results on the society that made it. I haven’t done this yet – all I gathered last night from Stückl was that deaths seem to decrease in the two years before a Passion play – as though people want to stay alive for the next one. In fact, in the 2010 there will be a 100-year old actor – the oldest in the history of the play. He was 90 last time, and inisisted on being in the next one.

Backstage there were lots of props for The Passion – some of them 200 or 300 years old. There was the wooden table for The Last Supper, made for the 1750 production and used in every performance since; ‘Roman’ shields and pikes from the early 19th century, crucifixes (enormous things!) a century old….

These people think long…

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe