Christopher Michel Captures The Long Now

Christopher Michel Named Artist-in-Residence at the Long Now Foundation

The Long Now Foundation is proud to announce Christopher Michel as Long Now Artist-in-Residence. A distinguished photographer and visual storyteller, Michel has documented Long Now’s founders and visionaries — including Stewart Brand, Kevin Kelly, Danny Hillis, Esther Dyson, and many of its board members and speakers — for decades. Through his portrait photographs, he has captured their work in long-term thinking, deep time, and the future of civilization.

As Long Now Artist-in-Residence, Michel will create a body of work inspired by the Foundation’s mission, expanding his exploration of time through portraiture, documentary photography, and large-scale visual projects. His work will focus on artifacts of long-term thinking, from the 10,000-year clock to the Rosetta Project, as well as the people shaping humanity’s long-term future.

Christopher Michel has made photographs of Long Now Board Members past and present. Clockwise from upper left: Stewart Brand, Danny Hillis, Kevin Kelly, Alexander Rose, Katherine Fulton, David Eagleman, Esther Dyson, and Danica Remy.

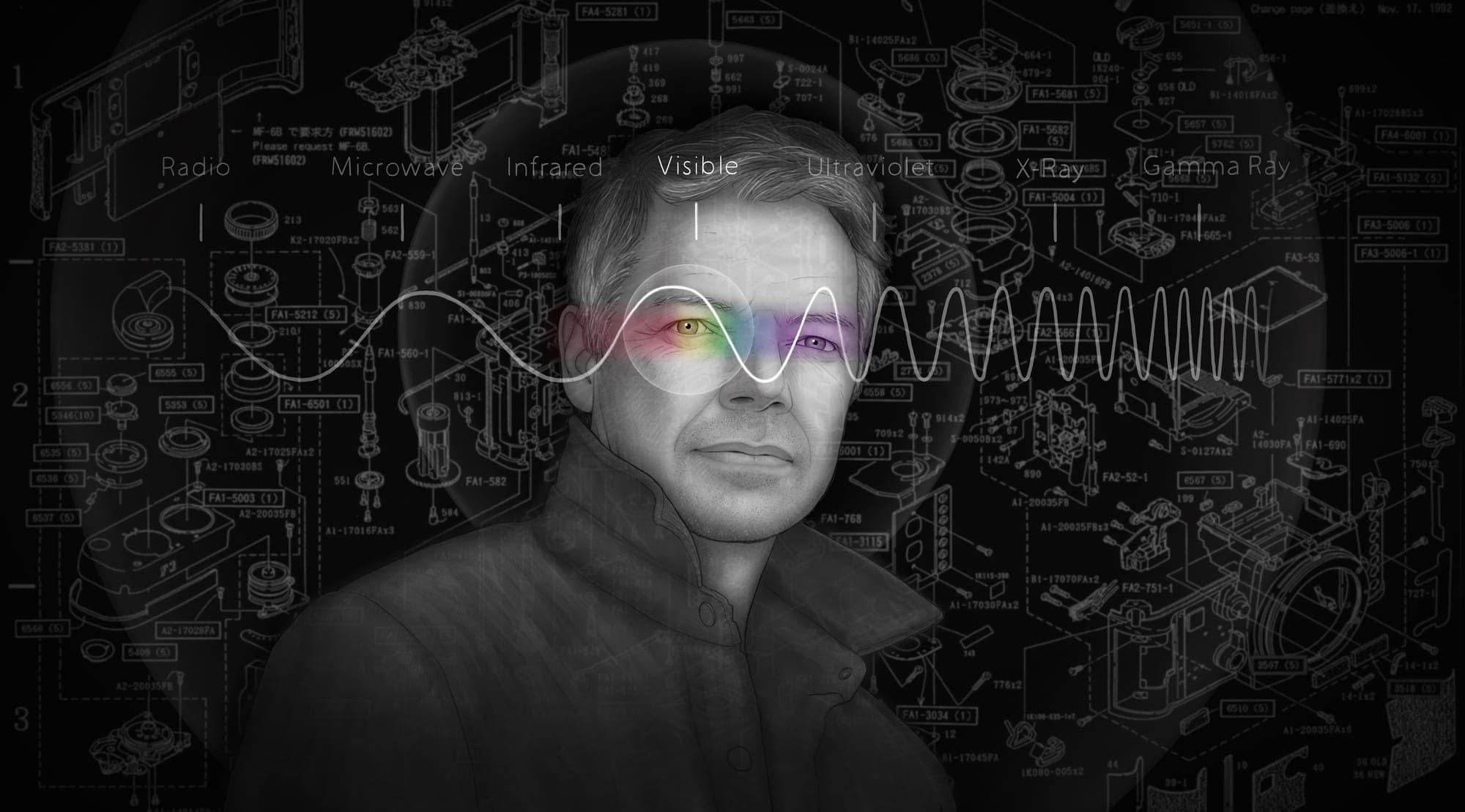

Michel will hold this appointment concurrently with his Artist-in-Residence position at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, where he uses photography to highlight the work of leading scientists, engineers, and medical professionals. His New Heroes project — featuring over 250 portraits of leaders in science, engineering, and medicine — aims to elevate science in society and humanize these fields. His images, taken in laboratories, underground research facilities, and atop observatories scanning the cosmos, showcase the individuals behind groundbreaking discoveries. In 02024, his portrait of Dr. Anthony Fauci was featured on the cover of Fauci’s memoir On Call.

A former U.S. Navy officer and entrepreneur, Michel founded two technology companies before dedicating himself fully to photography. His work has taken him across all seven continents, aboard a U-2 spy plane, and into some of the most extreme environments on Earth. His images are widely published, appearing in major publications, album covers, and even as Google screensavers.

“What I love about Chris and the images he’s able to create is that at the deepest level they are really intended for the long now — for capturing this moment within the broader context of past and future,” said Long Now Executive Director Rebecca Lendl.

“These timeless, historic images help lift up the heroes of our times, helping us better understand who and what we are all about, reflecting back to us new stories about ourselves as a species.”

Michel’s photography explores the intersection of humanity and time, capturing the fragility and resilience of civilization. His work spans the most remote corners of the world — from Antarctica to the deep sea to the stratosphere — revealing landscapes and individuals who embody the vastness of time and space. His images — of explorers, scientists, and technological artifacts — meditate on humanity’s place in history.

Christopher Michel’s life in photography has taken him to all seven continents and beyond. Photos by Christopher Michel.

Michel’s photography at Long Now will serve as a visual bridge between the present and the far future, reinforcing the Foundation’s mission to foster long-term responsibility. “Photography,” Michel notes, “is a way of compressing time — capturing a fleeting moment that, paradoxically, can endure for centuries. At Long Now, I hope to create images that don’t just document the present but invite us to think in terms of deep time.”

His residency will officially begin this year, with projects unfolding over the coming months. His work will be featured in Long Now’s public programming, exhibitions, and archives, offering a new visual language for the Foundation’s mission to expand human timescales and inspire long-term thinking.

In advance of his appointment as Long Now’s inaugural Artist-in-Residence, Long Now’s Jacob Kuppermann had the opportunity to catch up with Christopher Michel and discuss his journey and artistic perspective.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Long Now: For those of us less familiar with your work: tell us about your journey both as an artist and a photographer — and how you ended up involved with Long Now.

Christopher Michel: In a way, it’s the most unlikely journey. Of all the things I could have imagined I would've done as a kid, I am as far away from any of that as I could have imagined. My path, in most traditional ways of looking at it, is quite non-linear. Maybe the points of connectivity seem unclear, but some people smarter than me have seen connections and have made observations about how they may be related.

When I was growing up, I was an outsider, and I was interested in computers. I was programming in the late seventies, which was pretty early. My first computer was a Sinclair ZX 80, and then I went to college at the University of Illinois and Top Gun had just come out. And I thought, “maybe I want to serve my country.” And so I flew for the Navy as a navigator and mission commander — kind of like Goose — and hunted Russian submarines. I had a great time, I was always interested in computers, not taking any photographs really, which is such a regret. Imagine — flying 200 feet above the water for eight hours at a time, hunting drug runners or Russian subs, doing amazing stuff with amazing people. It just never occurred to me to take any photos. I was just busy doing my job. And then I went to work in the Pentagon in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations for the head of the Navy Reserve — I went to work for the bosses of the Navy.

If you'd asked me what I wanted to do, I guess I would've said, I think I want to go into politics and maybe go to law school. I'd seen the movie The Paper Chase, and I love the idea of the Socratic method. And then the Navy said, well, we’re going to send you to the Kennedy School, which is their school around public service. But then I ran into somebody at the Pentagon who said, "You should really go to Harvard Business School."

And I hadn't thought about it — I was never interested in business. He said that it's a really good degree because you can do lots of things with it. So I quit my job in the Navy and literally a week later I was living in Boston for my first day at Harvard Business School. It was a big eye-opening experience because I had lived in a kind of isolated world in the Navy — I only knew Navy people.

This was also a little bit before the pervasiveness of the internet. This is 01997 or 01996. People didn't know as much as they know now, and certainly entrepreneurship was not a thing in the same way that it was after people like Mark Zuckerberg. If you'd asked me what I wanted to do at Harvard, I would've said something relating to defense or operations. But then, I ran into this guy Dan Bricklin, who created VisiCalc. VisiCalc was one of the first three applications that drove the adoption of the personal computer. When we bought computers like the TRS 80 and Apple II in 01979 or 01980 we bought them for the Colossal Cave Adventure game, for VisiCalc, and for WordStar.

He gave a talk to our class and he said, "When I look back at my life, I feel like I created something that made a difference in the world." And it really got my attention, that idea of building something that can outlast us that's meaningful, and can be done through entrepreneurship. Before that, that was an idea that was just not part of the culture I knew anything about. So I got excited to do that. When I left Harvard Business School, I was still in the reserves and I had the idea that the internet would be a great way to connect, enable, and empower service members, veterans, and their families. So I helped start a company called Military.com, and it was one of the first social media companies to get to scale in the United States. And its concept may sound like a very obvious idea today because we live in a world where we know about things like Facebook, but this was five years before Facebook was created.

I raised a lot of money, and then I got fired, and then I came back and it was a really difficult time because that was also during the dot-com bubble bursting.

But during that time period, two interesting other things happened. The first: my good friend Ann Dwane gave me a camera. When I was driving cross country to come out here to find my fortune in Silicon Valley, I started taking some photos and film pictures and I thought, hey, my pictures are pretty good — this is pretty fun. And then I bought another camera, and I started taking more pictures and I was really hooked.

The second is actually my first connection to Long Now. What happened was that a guy came to visit me when I was running Military.com that I didn't know anything about — I'm not even sure why he came to see me. And he was a guy named Stewart Brand. So Stewart shows up in my office — he must've been introduced to me by someone, but I just didn't really have the context. Maybe I looked him up and had heard of the Whole Earth Catalog.

Anyways, he just had a lot of questions for me. And, of course, what I didn't realize, 25 years ago, is that this is what Stewart does. Stewart — somehow, like a time traveler — finds his way to the point of creation of something that he thinks might be important. He's almost a Zelig character. He just appears in my office and is curious about social media and the military. He served in the military, himself, too.

So I meet him and then he leaves and I don't hear anything of him for a while. Then, we have an idea of a product called Kit Up at Military.com. And the idea of Kit Up was based on Kevin Kelly’s Cool Tools — military people love gear, and we thought, well, what if we did a weekly gear thing? And I met with Kevin and I said, “Hey Kevin, what do you think about me kind of taking your idea and adapting it for the military?”

Of course, Kevin's the least competitive person ever, and he says, “Great idea!” So we created Kit Up, which was a listing of, for example, here are the best boots for military people, or the best jacket or the best gloves — whatever it might be.

As a byproduct of running these companies, I got exposed to Kevin and Stewart, and then I became better friends with Kevin. I got invited to some walks, and I would see those guys socially. And then in 02014, The Interval was created. I went there and I got to know Zander and I started making a lot of photos — have you seen my gallery of Long Now photos?

Christopher Michel's photos of the 10,000-year clock in Texas capture its scale and human context.

I've definitely seen it — whenever I need a photo of a Long Now person, I say, “let me see if there's a good Chris photo.”

This is an interesting thing that can happen in our lives, which are unintended projects. I do make photos with the idea that these photos could be quite important. There's a kind of alchemy around these photos. They're important now, but they're just going to be more important over time.

So my pathway is: Navy, entrepreneur, investor for a little while, and then photographer.

If there was a theme connecting these, it’s that I'm curious. The thing that really excites me most of all is that I like new challenges. I like starting over. It feels good! Another theme is the act of creation. You may think photography is quite a bit different than creating internet products, but they have some similarities! A great portrait is a created thing that can last and live without my own keeping it alive. It has its own life force. And that's creation. Companies are like that. Some companies go away, some companies stay around. Military.com stays around today.

So I'm now a photographer and I'm going all over the world and I'm making all these photos and I'm leading trips. Zander and the rest of the team invite me to events. I go to the clock and I climb the Bay Bridge, and I visit Biosphere 2. I'm just photographing a lot of stuff and I love it. The thing I love about Long Now people is, if you like quirky, intellectual people, these are your people. You know what I mean? And they're all nice, wonderful humans. So it feels good to be there and to help them.

In 02022, Christopher Michel accompanied Long Now on a trip to Biosphere 2 in Arizona.

During the first Trump administration, during Covid, I was a volunteer assisting the U.S. National Academies with science communication. I was on the board of the Division of Earth and Life Studies, and I was on the President’s Circle.

Now, the National Academies — they were created by Abraham Lincoln to answer questions of science for the U.S. government, they have two primary functions. One is an honorific, there's three academies: sciences, engineering, and medicine. So if you're one of the best physicists, you get made a member of the National Academies. It's based on the Royal Society in England.

But moreover, what’s relevant to everyone is that the National Academies oversee the National Research Council, which provides independent, evidence-based advice on scientific and technical questions. When the government needs to understand something complex, like how much mercury should be allowed in drinking water, they often turn to the Academies. A panel of leading experts is assembled to review the research and produce a consensus report. These studies help ensure that policy decisions are guided by the best available science.

Over time, I had the opportunity to work closely with the people who support and guide that process. We spent time with scientists from across disciplines. Many of them are making quiet but profound contributions to society. Their names may not be well known, but their work touches everything from health to energy to climate.

In those conversations, a common feeling kept surfacing. We were lucky to know these people. And we wished more of the country did, too. There is no shortage of intelligence or integrity in the world of science. What we need is more visibility. More connection. More ways for people to see who these scientists are, what they care about, and how they think.

That is part of why I do the work I do. Helping to humanize science is not about celebrating intellect alone. It's about building trust. When people can see the care, the collaboration, and the honesty behind scientific work, they are more likely to trust its results. Not because they are told to, but because they understand the people behind it.

These scientists and people in medicine and engineering are working on behalf of society. A lot of scientists aren't there for financial gain or celebrity. They're doing the work with a purpose behind it. And we live in a culture today where we don't know who any of these people are. We know Fauci, we might know Carl Sagan, we know Einstein — but people run out of scientists to list after that.

It’s a flaw in the system. These are the new heroes that should be our role models — people that are giving back. The National Academies asked me to be their first artist-in-residence, and I've been doing it now for almost five years, and it's an unpaid job. I fly myself around the country and I make portraits of scientists, and we give away the portraits to organizations. And I've done 260 or so portraits now. If you go to Wikipedia and you look up many of the Nobel Laureates from the U.S., they're my photographs.

I would say science in that world has never been under greater threat than it is today. I don't know how much of a difference my portraits are making, but at least it's some effort that I can contribute. I do think that these scientists having great portraits helps people pay attention — we live in that kind of culture today. So that is something we can do to help elevate science and scientists and humanize science.

And simultaneously, I’m still here at Long Now with Kevin and Stewart, and when there's interesting people there, I make photos of the speakers. I've spent time during the leadership transition and gotten to know all those people. And we talked and asked, well, why don't we incorporate this into the organization?

In December 02024, Christopher Michel helped capture incoming Long Now Executive Director Rebecca Lendl and Long Now Board President Patrick Dowd at The Interval.

We share an interest around a lot of these themes, and we are also in the business of collecting interesting people that the world should know about, and many of them are their own kind of new heroes.

I was really struck by what you said about how much with a really successful company or any form of institution, but also, especially, a photograph, put into the right setting with the right infrastructure around it to keep it lasting, can really live on beyond you and live on beyond whoever you're depicting.

That feels in itself very Long Now. We don't often think about the photograph as a tool of long-term thinking, but in a way it really is.

Christopher Michel: Well, this transition that we're in right now at Long Now is important for a lot of reasons. One is that a lot of organizations don't withstand transitions well, but the second is, these are the founders. All of these people that we've been talking about, they're the founders and we know them. We are the generation that knows them.

We think they will be here forever, and it will always be this way, but that's not true. The truth is, it's only what we document today that will be remembered in the future. How do we want the future to think about our founders? How do we want to think about their ideas and how are they remembered? That applies to not just the older board members — that applies to Rebecca and Patrick and you and me and all of us. This is where people kind of understate the role of capturing these memories. My talk at the Long Now is about how memories are the currency of our lives. When you think about our lives, what is it that at your deathbed you're going to be thinking about? It'll be this collection of things that happen to you and some evaluation of do those things matter?

I think about this a lot. I have some training as a historian and a historical ecologist. When I was doing archival research, I read all these government reports and descriptions and travelers' journals, and I could kind of get it. But whenever you uncovered that one photograph that they took or the one good sketch they got, then suddenly it was as if a portal opened and you were 150 years into the past. I suddenly understood, for example, what people mean when they say that the San Francisco Bay was full of otters at that time, because that's so hard to grasp considering what the Bay is like now. The visual, even if it's just a drawing, but especially if it's a photograph, makes such a mark in our memory in a way that very few other things can.

And, perhaps tied to that: you have taken thousands upon thousands of photos. You've made so many of these. I've noticed that you say “make photos,” rather than “take photos.” Is that an intentional theoretical choice about your process?

Christopher Michel: Well, all photographers say that. What do you think the difference is?

Taking — or capturing — it's like the image is something that is out there and you are just grabbing it from the world, whereas “making” indicates that this is a very intentional artistic process, and there are choices being made throughout and an intentional work of construction happening.

Christopher Michel: You're basically right. What I tell my students is that photographers visualize the image that they want and then they go to create that image. You can take a really good photo if you're lucky. Stuff happens. You just see something, you just take it. But even in that case, I am trying to think about what I can do to make that photo better. I'm taking the time to do that. So that's the difference, really.

The portraits — those are fun. I'd rather be real with them, and that's what I loved about Sara [Imari Walker]. I mean, Sara brought her whole self to that photo shoot.

On the question of capturing scientists specifically: how do you go about that process? Some of these images are more standard portraits. Others, you have captured them in a context that looks more like the context that they work in.

Christopher Michel: I'm trying to shoot environmental portraits, so I often visit them at their lab or in their homes — and this is connected to what I’ve talked about before.

We've conflated celebrity with heroism. George Dyson said something to the effect of: “Some people are celebrities because they're interesting, and some people are interesting because they're celebrities.”

I think that society would benefit from a deeper understanding of these people, these scientists, and what they're doing. Honestly, I think they're better role models. We love actors and we love sports stars, and those are wonderful professions. But, I don't know, shouldn't a Nobel laureate be at least as well known?

There’s something there also that relates to timescales. At Long Now, we have the Pace Layers concept. A lot of those celebrities, whether they're athletes or actors or musicians — they're all doing incredible things, but those are very fast things. Those are things that are easy to capture in a limited attention span. Whereas the work of a scientist, the work of an engineer, the work of someone working in medicine can be one of slow payoffs. You make a discovery in 02006, but it doesn't have a clear world-changing impact until 02025.

Christopher Michel: Every day in my job, I'm running into people that have absolutely changed the world. Katalin Karikó won the Nobel Prize, or Walter Alvarez — he’s the son of a Nobel laureate. He's the one who figured out it was an asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Diane Havlir, at UCSF — she helped create the cocktail that saved the lives of people who have AIDS. Think about the long-term cascading effect of saving millions of HIV-positive lives.

I mean, is there a sports star that can say that? The impact there is transformational. Look at what George Church is doing — sometimes with Ryan Phelan. This is what they're doing, and they're changing every element of our world and society that we live in. In a way engineering the world that we live in today, helping us understand the world that we live in, but we don't observe it in the way that we observe the fastest pace layer.

We had a writer who wrote an incredible piece for us about changing ecological baselines called “Peering Into The Invisible Present.” The concept is that it's so hard to observe the rate at which ecological change happens in the present. It's so slow — it is hard to tell that change is happening at all. But then if you were frozen in when Military.com was founded in 01999, and then you were thawed in 02025, you would immediately notice all these things that were different. For those of us who live through it as it happens, it is harder to tell those changes are happening, whereas it's very easy to tell when LeBron James has done an incredible dunk.

Christopher Michel: One cool thing about having a gallery that's been around for 20 years is you look at those photos and you think, “Ah, the world looked a little different then.”

It looks kind of the same, too — similar and different. There's a certain archival practice to having all these there. Something I noticed is that many of your images are uploaded with Creative Commons licensing. What feels important about that to you?

Because for me, the way for these images to become in use and to become immortal is to have it kind of spread throughout the internet. I’m sure I’ve seen images, photographs that you made so many times before I even knew who you were, just because they're out there, they enter the world.

Christopher Michel: As a 57-year-old, I want to say thank you for saying that. That's the objective. We hope that the work that we're doing makes a difference, and it is cool that a lot of people do in fact recognize the photos. Hopefully we will make even more that people care about. What's so interesting is we really don't even know — you never know which of these are going to have a long half life.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe