A Trips Festival for the Digital Age

Sónar seeks to bridge the worlds of art and technology, the popular and the avant-garde, and club culture and cyberculture

LEARN MORE

Two series of radio transmissions are currently beaming through interstellar space — headed, their senders hope, for intelligent life on a distant planet. The transmissions contain 38 encoded pieces of music, each 10 seconds in length, created by far-out but nonetheless Earth-bound musicians.

At the time of this writing, the first of the transmissions will have recently exited the Oort cloud, an expanse of icy cometary nuclei made of cosmic dust. It is expected to reach its destination, the exoplanet gj273b, on November 3rd, 02030 — 12.5 years after it was sent from Earth. The second transmission will arrive six months later.

The exoplanet, known as Luyten’s Star, appears to meet the necessary conditions to harbor life. If it does, and if it is intelligent life, and if its denizens deign to reply, the soonest Earthlings can hope to hear back is 02043.

For the organizers of Sónar — an arts, design and electronic music festival in Barcelona, Spain — that would constitute perfect timing. The festival partnered with METI (Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence) to send the radio transmissions for its 25th anniversary celebration, with the hope that it might get a response in time for its 50th.

A multi-decade project to contact alien life might not seem like typical festival fare. But Sónar isn’t a typical festival. For over a quarter century, it has sought to bridge the worlds of art and technology, the popular and the avant-garde, and club culture and cyberculture. Each edition of the festival offers a glimpse of possible futures and frontiers, from the latest technological advances in artificial intelligence and quantum computing to the next trends in music and multimedia art. The music festival is coupled with Sónar+D, a four-day technology and design conference of talks, workshops, immersive experiences, and exhibitions.

Sónar epitomizes what Stanford historian Fred Turner calls a network forum — a place wherein “members of multiple communities [can] meet and collaborate and imagine themselves as members of a single community,” thereby “facilitat[ing] the formation of both new networks and new contact languages.”

José Luis de Vicente, the lead curator of Sónar+D, describes the festival’s curatorial approach as anti-disciplinary.

“Sónar pioneered a model where the lines between musician, visual artist, technologist and sometimes even entrepreneur are really blurred,” de Vicente tells me. “We wanted to be a vessel for people who transition between those spaces.”

He pauses — realizing, perhaps, that he’s made too bold a claim.

“You know, there’s a problem in this community where we always think we’re inventing everything from scratch,” he says. “But there’s easily 50 years of tradition in this kind of thing.”

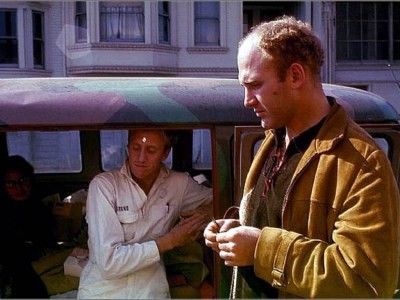

Scenes from the Trips Festival in Longshoreman’s Hall, 01966.

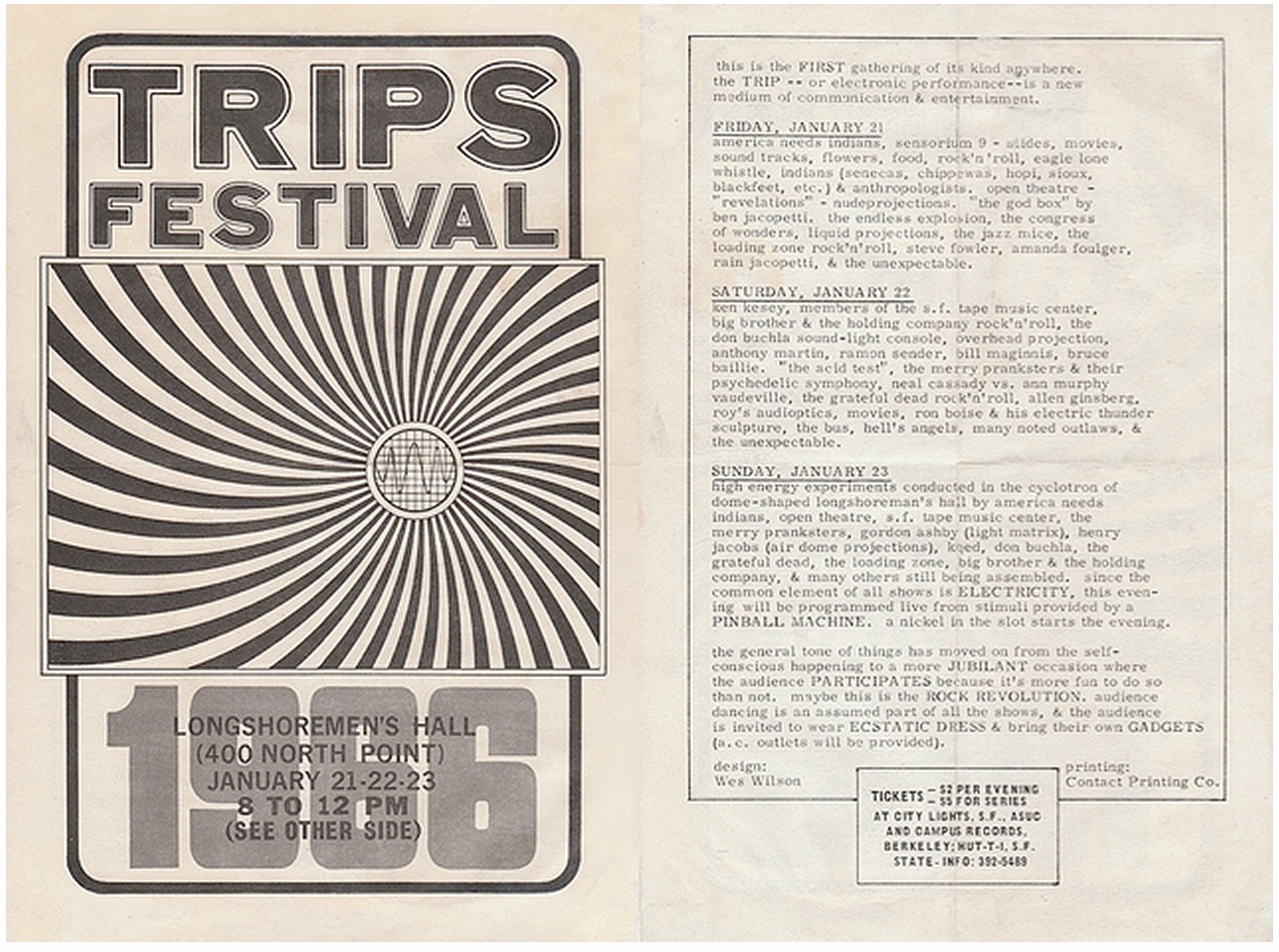

That tradition began, de Vicente says, with the 01966 Trips Festival, a watershed moment in the history of American counterculture that inaugurated the psychedelic sixties. The three-day event, held in San Francisco’s Longshoreman’s Hall, was co-organized by future Long Now cofounder Stewart Brand, whom de Vicente calls a “godfather of digital culture.” At the time, Brand was part of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, an outfit of psychedelic enthusiasts who had begun throwing parties (called ‘Acid Tests’) some months prior.

The Acid Tests were small, haphazard and sketchy affairs, taking place in houses, on beaches, and in small music venues. Attendees helped themselves to lsd served out of trash containers and danced all night under multicolored lights to the improvised noodlings of an up-and-coming blues band called the Warlocks, soon to be the Grateful Dead.

There was talk amongst the Pranksters of throwing a bigger party — fire a flare into the San Francisco sky and see who comes. But the Pranksters, for all their spontaneity, lacked a certain organizational focus.

“I knew in my heart that we were not going to be able to pull that off,” Brand recalled, “but that it ought to happen.” Brand, along with electronic music composer Ramón Sender, took it upon himself to make it so. They secured Longshoreman’s Hall as a venue and enlisted the help of concert promoter Bill Graham.

The event was promoted as an LSD trip sans LSD, though, as Tom Wolfe notes in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (01968), many of the 10,000 attendees arrived “bombed out of their gourds” anyway. The Bay Area avant-garde showed in full force, as did the musicians of what would soon be dubbed the San Francisco sound. The psychedelic experience was approximated through the use of light projections, stroboscopes, music, and immersive, participatory art.

A network forum in the Turner sense, the Trips Festival, writes curator Andrew Blauvelt, “[made] visible a large and fast-growing community that was now becoming increasingly legible and identifiable to itself.” Or, as Wolfe puts it: “The Haight-Ashbury era began that weekend.”

“The Trips Festival was the original event saying a show should be a multi-sensorial experience,” de Vicente says. It was also an early originator of the idea that engineers and artists could work together in fruitful collaboration, a model that drove the San Francisco Bay Area’s transition from counterculture to cyberculture over the second half of the 20th century. Finally, the Trips Festival introduced the notion of “no spectators,” which Stewart Brand defines as “the idea that an audience shows up to a certain kind of event expecting to do something, not just to see something.” “No Spectators” later became a guiding principle of both rave culture and festivals like

Burning Man.

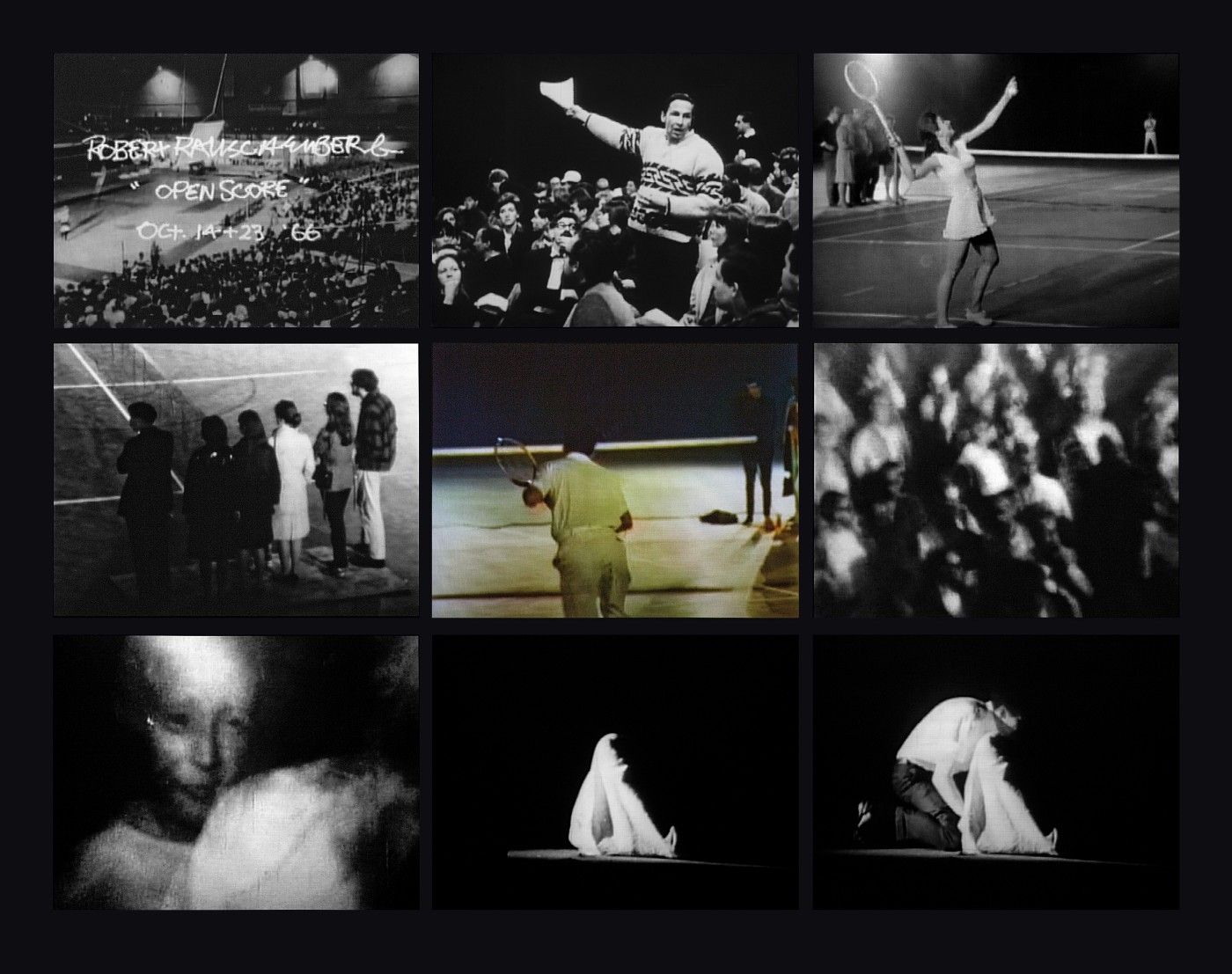

Another lesser known but equally consequential chapter in the multimedia artistic tradition that gave rise to Sónar occurred in New York City, at the 69th Regiment Armory, nine months after the Trips Festival. 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering sought to bridge the worlds of art and technology through showcasing collaborations between avant-garde artists and engineers from Bell Labs.

The project was started by Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver and graphic artist Robert Rauschenberg, who later founded Experiments in Art and Technology to further explore the artistic possibilities of electric space. In the 10 months leading up to 9 Evenings, Bell Labs engineers worked with artists John Cage, Lucinda Childs, Merce Cunningham, Öyvind Fahlström, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, David Tudor, and Robert Whitman, as well as Robert Rauschenberg himself, to incorporate technologies that would enable new forms of artistic expression. More than 10,000 people attended the exhibition, where they witnessed the first use of television projection, Doppler sonar and the transmission of wireless sound in a theatrical, artistic context.

“9 Evenings didn’t really look like an exhibition in a museum,” de Vicente says. “It looked way more like what Sónar By Night looks like — which is a huge dark hangar with thousands of people watching something that you wouldn’t naturally recognize as a performance.”

Fast forward to 01994. Analog has given way to digital, the “happening” has given way to the rave and the club, and the amplified electricity of psychedelic rock has given way to the thumping bass of electronic dance music.

“DJs were already superstars,” writes music journalist James Davidson, “but the thriving club scene needed its Mecca — and […] it was left to three Catalans to give birth to the festival that now defines its genre.”

Sónar was founded by music journalist Ricard Robles and musicians/visual artists Enric Palau and Sergio Caballero. They billed the first gathering in 01994 as the “Festival of Advanced Music and Multimedia Art.” A Record and Technology Fair — what would later evolve into the Sónar+D conference — took place alongside the festival, which was attended by some 6,000 people. (Today, attendance at Sónar has swelled to over 126,000 people, with approximately 6,000 professionals participating in its Sónar+D conference.)

“When Sónar started in the mid-01990s, it contained that element [from the Trips Festival and 9 Evenings] of investigating this spectrum that an event can be both popular and avant-garde at the same time,” de Vicente says. “You have this clash of people who would normally be in the space of experimental electronics with the people who are part of the audience of club culture, techno and house, and they mingle in very interesting ways.”

Over the years, this mingling expanded to include members of research departments in universities and the first hacker spaces, which emerged as new centers of creativity with the rise of the web.

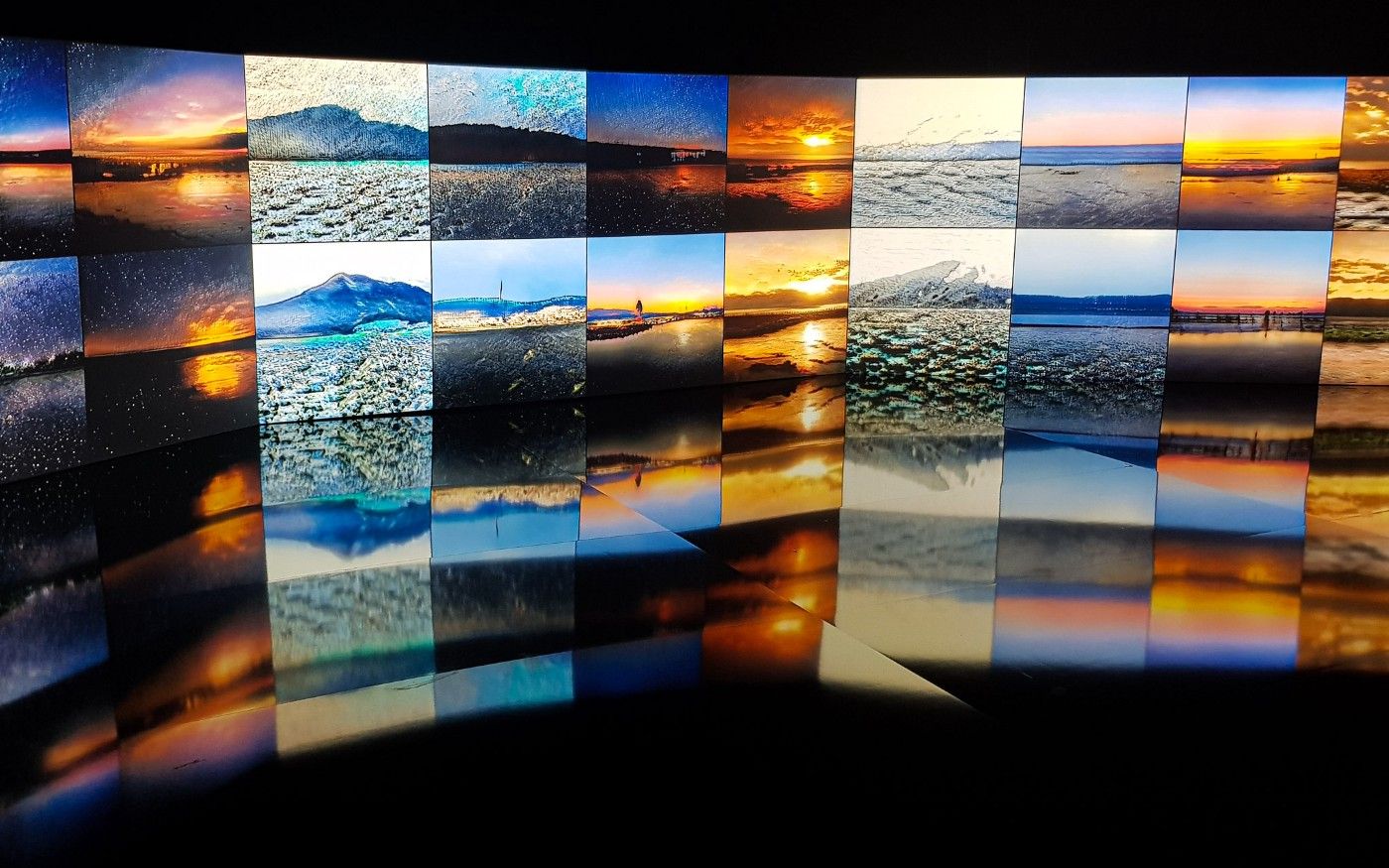

It’s a heady, and at times overwhelming, brew. Days at Sónar start soberly at the Fira Montjuic convention center, with lanyard-donning techies attending panels and talks on quantum computing, artificial intelligence, and the future of the internet; perusing a technology trade fair (dubbed the SónarHub) where hackers hawk their latest prototypes; or experiencing the latest in cutting edge, immersive multimedia art, like Memo Akten’s Deep Meditations installation, which features images and sounds generated by a neural network trained on Flickr photo tags such as ‘everything’, ‘life’, ‘god’, and ‘universe’.

The character of the event changes markedly in the afternoon, when Sónar by Day begins. Heavy bass echoes through the festival grounds that now teem with club culture enthusiasts, attendance swelling by the hour. At the SónarVillage, an outdoor pavilion flanked by food trucks and beer stalls, DJs regale the paella-eating masses.

Left: Holly Herndon performing PROTO at Sónar 02019. Right: Daito Manabe performing Dissonant Imaginary at Sónar 02019.

On smaller stages throughout the venue, avant garde artists debut new visions of the ambient frontier, like musician and programmer Holly Herndon’s show/album PROTO, which she collaborated on with an artificial intelligence she dubs “Spawn,” or Daito Manabe’s AV tech experience that uses an MRI scanner that visualizes brain states reacting to the music being played.

Left: Musician, visual artist, and Long Now co-founder Brian Eno delivering the keynote address at Sónar 02016. Right: Massive Attack’s Andrew Melchior and Robert Del Naja in conversation at Sónar 02019.

A keynote address is delivered in the late afternoon in the convention auditorium. (In 02016, that honor fell to Long Now cofounder Brian Eno.) This year, Robert Del Naja, the frontman of Massive Attack, discussed his band’s methodology of combining generative art, music and technology, as well as its recent project of encoding its debut album into DNA that can be sprayed from an aerosol can.

Once darkness falls, attendees flood a different venue across Barcelona, the Fira Gran Via, for Sónar by Night. Tens of thousands of people pack overcrowded, sweaty hangars and dance until dawn, taking occasional breaks to hit the bumper car course. The music here is decidedly more mainstream, and over the years has featured the likes of Daft Punk, Kraftwerk, Björk, and Thom Yorke. DJs dominate the hours after midnight, with some playing six-hour sets. Once the sun rises, Sónar attendees are provided a brief reprieve before the festivities begin again in the late morning.

“Sónar is not a festival that values sleeping,” a Sónar veteran told me at Del Naja’s keynote. “But the future is worth staying up for.”

In recent years, Sónar has expanded its time horizon of the future to focus on coming centuries and millennia. As humanity grapples with multigenerational challenges like climate change and rapid technological advance, there’s been an increased emphasis on long-term thinking at the festival — evidenced by both the themes and projects of Sónar and the ideas presented by speakers themselves.

“There is a deficiency of long-term thinking in western culture,” Jay Springett, a London-based theorist, said at a panel on the future of the internet at this year’s Sónar+D. “It will be vital that we think at multigenerational time depths about everything from internet technologies to tree planting, given the challenges that humanity faces. Our modern world seeks to focus us towards the short-term, and praises quarterly growth. But in the real world, away from high-frequency ledger entries and global capital flows, it takes 100–120 years for an oak tree to grow from seed to full canopy height. It takes three human generations to grow a tree. This is real growth. And I’d like to propose that everything that occurs in the duration between the decision to plant an acorn to the tree’s full grown crown is short-term thinking.”

SónarCalling, the festival’s attempt to message extraterrestrials, is Sónar’s most ambitious long-term project to date. It served as an organizing principle for the festival’s 25th anniversary, grounding its lines of inquiry around questions of exploration, messaging, intelligence, and designing for longevity.

“Sónar has always been about exploring and scanning the musical cultures of the planet,” de Vicente says. Broadening Sónar’s scope beyond Earth, de Vicente says, requires thinking in different scales of space — which necessarily implies deeper explorations of time.

To that end, Sónar invited Alexander Rose, Executive Director at Long Now, to speak about the 10,000-year clock and what it has taught Long Now about thinking through problems in millennial time scales. Rose emphasized that the central value of the clock lies not in the object itself, but in the myth of long-term thinking it can help inspire.

“Some of the truly multi-millennial artifacts we have in civilization are stories,” Rose said, citing the Epic of Gilgamesh as an example. “What we’re really trying to do is build a story. The clock is the mechanism by which a myth can hopefully be created. If the clock lasts, great. But if it creates enough of a story, that myth could probably outlast the clock by thousands of years.”

Alexander Rose’s talk from Sonar+D 02018.

“Some of the truly multi-millennial artifacts we have in civilization are stories,” Rose said, citing the Epic of Gilgamesh as an example. “What we’re really trying to do is build a story. The clock is the mechanism by which a myth can hopefully be created. If the clock lasts, great. But if it creates enough of a story, that myth could probably outlast the clock by thousands of years.”

The engineering challenges in building a 10,000-year object were unprecedented, to be sure. But with the clock nearing completion, the real challenge, Rose said, is building a 10,000-year institution that keeps the ideas behind the clock relevant.

“We’re crossing an interesting time,” Rose said. “By the time we’re about 25 years old — the same age as this festival — we will have finished this very experimental phase, and will move into a phase where this very notional, perfect object that we’ve talked about is now going to be real and in the world and open to criticism. So moving forward, it’s going to be a very different institution, I think, than it has been up to now.”

Sónar finds itself in a similar moment of reflection, now that it has reached its 25-year milestone. “We are trying to create a conversation that can only happen at 25-year intervals,” de Vicente says of the SónarCalling project. “It’s a way of asking what things will be like at the 50th edition of the festival.”

Asking what the festival will be like in 25 years is implicitly a question about where things stand today. De Vicente, who was part of that first generation of technologists who started getting online in the early 01990s when the web was undergirded by techno-utopian principles, has lately found himself questioning what kind of art and technology event digital culture needs in its current fraught, polarized moment.

“We have never been in such a critical moment of dissatisfaction, of acknowledgment that a lot of these cultures that we built are not making society a better place,” he says. “It’s hard not to be cynical. But at the same time, it’s pretty exciting. These events are artifacts, they are devices. We’re going to need different kinds of devices for shaping the next stage of digital culture, to recapture that energy of possibility from the early days of the web.”

There’s reason to be optimistic that Sónar, as one of the world’s most forward-looking festivals, will be a leader in shaping what that next stage looks like, as it has been in the past. And that in 02043, if an intelligent civilization from beyond the solar system decides we’re worthy of a response, there’ll be a crowd of artists and technologists dancing to the strange sounds of an avant-garde future in the city of Barcelona, eager to receive the message.

Learn More:

- Keep up with the SonarCalling audio transmissions as they make their way across the cosmos.

- Watch talks from this year’s edition of Sónar+D.

- Read Long Now’s interview with Sónar curator José Luis de Vicente about the role of art in addressing climate change.

- Read Fred Turner’s From Cyberculture to Counterculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism (02006) for more on the history that gave rise to events like Sónar.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe