Long-term Building in Japan

It is striking that this part of Japan houses two sets of structures, both of nearly equal age, and both made of largely ephemeral materials that have lasted over 14 centuries through totally different mechanisms and religions.

When I started working with Stewart Brand over two decades ago, he told me about the ideas behind Long Now, and how we might build the seed for a very long-lived institution. One of the first examples he mentioned to me was Ise Shrine in Japan, which has been rebuilt every 20 years in adjacent sites for over 1,400 years. This shrine is made of ephemeral materials like wood and thatch, but its symbiotic relationship with the Shinto belief and craftsmen has kept a version of the temple standing since 692 CE. Over these past decades many of us at Long Now have conjured with these temples as an example of long-term thinking, but it had not occurred to me that I might some day visit them.

That is, until a few years ago, when I came across a news piece about the temples. It announced that the shrine’s foresters were harvesting the trees for the next rebuild, and I decided to do some research to find out how and when visitors could go see the one temple being replaced by the next. This research turned out to be very difficult, in part because of the language barrier, but also because the last rebuild took place well before the world wide web was anything close to ubiquitous. I kept my ear out and asked people who might know about the shrines, but did not get very far.

Then, one morning in late September, Danny Hillis called to tell me that Daniel Erasmus, a Long Now member in Holland, had learned that the shrine transfer ceremony would be taking place the following Saturday. Danny said he was going to try and meet Daniel in Ise, and wanted to know if he should document it. I told him he wouldn’t need to, because I was going to get on a plane and meet them there.

Ise Shrine

The next few days were a blur of difficult travel arrangements to a rural Japanese town where little English was spoken and lodging was already way over-booked. I was greatly aided by a colleague’s Japanese wife, who was able to find us a room in a traditional ryokan home-stay very close to the temples. I also put the word out about the trip, and Ping Fu from the Long Now Board decided to join us, as well.

A few days later I met Ping at SFO for our flight to Osaka. Danny Hillis and Daniel Erasmus would be coming in from Tokyo a day later. We would stay the night in Osaka and then take the train to Ise. I found out that one of the other sites in Japan I had always wanted to visit was also close by: the Buddhist temples of Nara, considered to be some of the oldest continuously standing wooden structures in the world. We would be visiting Nara after our visit to Ise.

After landing, Ping and I spent a jet-lagged evening wandering around the Blade Runner streets of Osaka to find a restaurant. In Japan the best local food and drink are often tiny neighborhood affairs that only seat 5–10 people. Ping’s ability to read Kanji characters, which transfer over from Chinese, proved to be very helpful in at least figuring out if a sign was for a restaurant or a bathhouse.

The next morning we headed east on a train to Ise eating “fast food” — morsels of fish and rice wrapped in beautiful origami of leaves. This was not one of the bullet trains; Ise is a small city whose economy has been largely driven by Shinto pilgrims for the last two millennia. A few decades before the birth of Christ, a Japanese princess is said to have spent over twenty years wandering Japan, looking for the perfect place to worship. Around year 4 of the current era she found Ise, where she heard the spirits whisper that this “is a secluded and pleasant land. In this land I wish to dwell.” And thus Ise was established as the Shinto spiritual center of Japan.

This is probably a good time to say a bit more about Shinto. While it is referred to often as a religion with priests and temples, there is actually a much deeper explanation, as with most things in Japan. Shinto is the indigenous belief system that goes back to at least 6 centuries BCE and pre-dates any religions in Japan — including Buddhism, which did not arrive until a millennium or so later. Shinto is an animist world view, which believes that spirits, or Kami, are a part of all things. It is said that nearly all Japanese are Shinto, even though many would self-describe as non-religious, or Buddhist. There are no doctrines or prophets in Shinto; people give reverence to various Kami for different reasons throughout their day, week, or life.

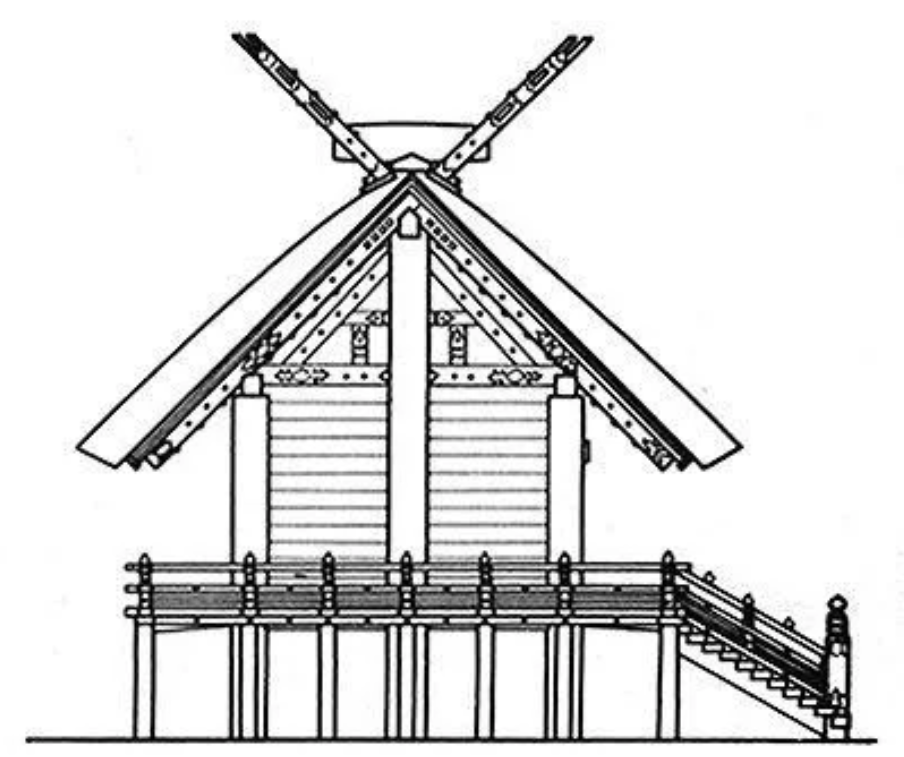

There are over 80,000 Shinto temples, or Jinja, in Japan, and hundreds of thousands of Shinto “priests” who administer them. Of all of these temples, the structures at Ise, collectively referred to as Jingū, are considered the most important and the most highly revered. And of these, the Naikū shrine, which we were there to see, tops them all, and only members of the Japanese imperial family or the senior priests are allowed near or in the shrine. The simple yet stunningly beautiful Kofun-era architecture of the temples dates back over 2500 years, and the traditional construction methods have been refined to an unbelievably high art — even when compared to other Japanese craft.

My understanding of how this twenty-year cycle became a tradition is that these shrines were originally used as seed banks. Since these were made of wood, they would need to be replaced and the seed stock transferred from one to the other. The design of the buildings and even the thatch roof are highly evolved for this. When there are rains, the thatch roof gets heavier, weighing down the wood joinery and making it water-tight. In the dry season, it gets lighter and the gaps between the wood are allowed to breathe again, avoiding mold.

On Friday afternoon we arrived at Ise and, within a short walk, had checked in at our very basic ryokan hotel. The location was perfect, however, as we were directly across from the Naikū shrine area entrance. The town of Ise lies in a mainly flat lowland area across the bay from Nagoya (to the North). Its temples are the end destination of a pilgrimage route which people used to traverse largely by foot, and over the last 2,000 years various food and accommodation services have evolved to cater to those visitors.

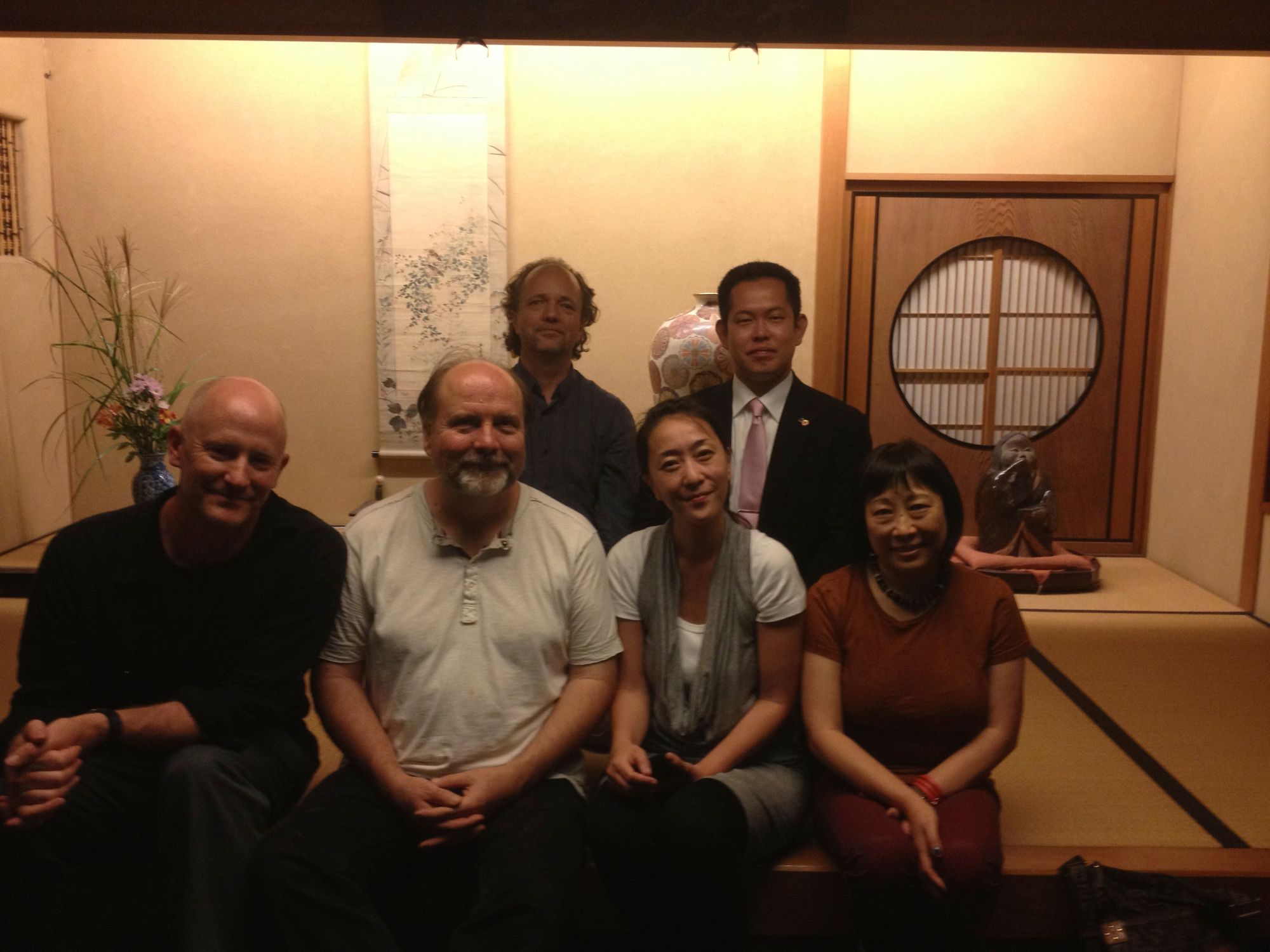

Ping and I wandered toward the entry and met up with Danny, Daniel, and Maholo Uchida, a friend of Daniel’s who is a curator at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation in Tokyo. Maholo would prove to be an absolutely amazing guide through the next 24 hours, and most of what I now understand about Ise and its customs comes from her.

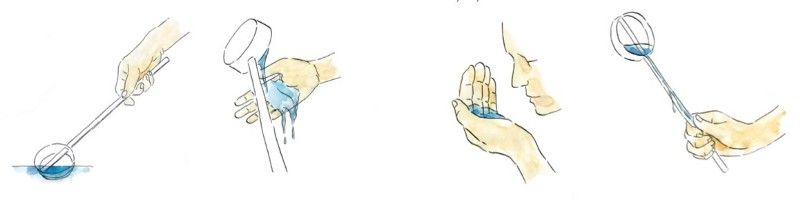

We traversed a small bridge and passed a low pool of water with a small roof over it. These Temizuya basins, found at the entry to all Shinto shrines, are a place to purify yourself before entry. As with all things in Japan — especially visits to shrines — there is an order and ceremony to washing your hands and mouth at the Temizuya. After this purification, we headed into the forest on a wide path of light grey gravel that crunched underfoot.

Just where the forest begins, we approached a large and beautifully crafted Shinto arch. These are apparently made from the timbers of an earlier shrine after it has been deconstructed. Visitors generally pass through three consecutive arches to enter a Shinto shrine area. Maholo quickly educated us on how to bow as we passed under the first arch (it is different for entering versus leaving) and on proper path walking etiquette. It is apparently too prideful to walk in the middle of the path: you should walk to one side, which is generally — but not always — the left side. As with everything here, there was etiquette to follow which was steeped in tradition and rules that would take a lifetime to understand fully.

As we walked from arch to arch, Maholo explained that the forest here had historically been used exclusively to harvest timbers for all the shrines, but over the last millennia they had been harvested too heavily for various war efforts, or lost in fire. Since the beginning of this century the shrines’ caretakers have been bringing these forests back, and expect them to be self-sustaining again within the next two or three rebuilding periods — 40 to 60 years from now.

Passing through a sequence of arches, we arrived at the Naikū shrine sanctuary area. This area includes a place that sells commemorative gifts. At this point you might be thinking “tourist trap gift shop,” but this adjacent structure is at least centuries old and of course perfectly fits the aesthetic. Instead of cheap plastic trinkets and coffee mugs, it offered hand-screened prints on wood from the last temple deconstruction, as well as calligraphic stamps for your shrine ‘passport’.

Adjacent to the gift shop is the walled-off section of the Naikū shrine. Visitors are allowed to approach one spot, where there is a gap in the wall, and see a glimpse of the main temples. On the left, the one completed in 01993 has begun to grey (pictured below), and on the right gleams the newly finished temple, a dual view only seen once every 20 years. After this event, they will begin disassembly of the old shrine, and will leave just a little doghouse-sized structure in its place for the next two decades.

The audience for this event consisted of only a few hundred people. Maholo explained that this rebuilding has been going on for eight years, and that many people come for different parts of the process, including the harvesting of the trees, the blessing of the tools, the milling of the timbers, the placement of the white river foundation stones, and so on.

As we stood there, crowds were gathering, and we noticed behind us a series of chests that were roped off in the courtyard area. Some of these were plain wood and some of them were lacquered. These chests contained the temple “treasures” that are moved from the old temple to the new. Some are re-created every 20 years by the greatest craftspeople in Japan, some have been moved from temple to temple for 14 centuries, and some are totally secret to all but the priests. The treasures are what the Kami spirits follow from one temple to the next as they are rebuilt. So the Shinto priests move the treasures when the new temple is ready, and the Kami spirits move sometime in the night to follow them in to their new home.

As we took photos, a large group of priests and press started lining up. We were ushered over to the gift building area and held back by white gloved security personnel. It was a bit comical as they did not seem to know exactly what to do with us. Since this ceremony happens only every 20 years, it is unlikely that any of the staff were present at the last occasion: while this is one of the oldest events in the world, it is simultaneously brand new. It was very apparent that none of the ritual acts were performed for the audience. All of this ceremony was designed for the benefit of the Kami spirits, not for people’s entertainment, and much of what we saw were glimpses through trees from a distance. While it was hard to see everything, we all agreed that this perspective made the tradition much more magical and interesting than if it had all been laid bare.

Without fanfare, the princess of Japan led a march of hundreds of Ise priests down the path that we had just walked, and they all lined up in rows next to the chests. After a ceremony with nearly 30 minutes of bowing, the chests were carried into the sanctuary and placed into the new shrine (though this was out of view).

Then they came back out, lined up again, and went through a series of wave like bows before being led away by the princess.

All very calm, very simple, and without any hurrah. The Kami would soon follow the treasures into their new home.

What was a real surprise was to learn that there are 125 shrines in Ise: all are rebuilt every 20 years, but on different schedules. This is also done at other Shinto shrine sites, but not always every 20 years; some have cycles as long as 60 years. Once we were allowed to wander around again, we hiked up the hill to some of the other temples, all built for different Kami. Some recently-built shrines stood next to the ones awaiting deconstruction, and some stood alone. These are all made with similar design and unerring construction, and unlike the main temple, we were allowed to walk right up to these and take pictures.

We left the forest on a different path as the sun set, bowing our exit bows twice after each of the three arches. We wandered through the town a bit and I suggested we find a local bar that offered the traditional Japanese “bottle keep” so we could drink half of a bottle and leave it on the shelf to return in 20 years for the other half.

Maholo took us to a tiny alley where she peeked into a few shoji screens, eventually finding us the right place. It had only eight or so seats, and the proprietor was a lovely Japanese grandmother. We ordered a bottle of Suntory whiskey and began to pour.

The barkeep was amazed to find out how far we had traveled to see the ceremony, and put our dated Long Now bottle on the highest shelf in a place of honor.

Afterwards, Maholo had arranged for us to have dinner at a beautiful ryokan with one of the Shinto priests, who had come in from Tokyo to help with the events in Ise. We were served course after course of incredible seafood while he gracefully answered our questions, all translated by Maholo.

We learned that the priests who run Ise are their own special group within the Shinto organization, and don’t really follow the line of the main organization. For instance, when several of the Shinto temples were offered UNESCO world heritage site status, they politely declined. I can just imagine them wondering why they would need an organization like UNESCO, that is not even half a century old, to tell them that they had achieved “historic” status. I suspect that maybe in a millennium or two, if UNESCO is still around, they might reconsider.

The next morning we returned to Naikū to catch a glimpse through the trees of the priests bringing the Kami their first meal. The Kami are fed in the morning and evening of each day from a kitchen building behind the temple sanctuary. We watched priests and their assistants bringing in chests of food as we chatted with an American who works for the Shinto central office in Tokyo. He had put together a beautiful book about the shrines at Ise, The Soul of Japan, to which he later sent me a link to share in this report.

Afterwards, we also visited the small but amazing museum at Ise that displays some of the “treasures” from past shrines, a temple simulacrum, and a display documenting the 1400-year reconstruction history along with the beautiful Japanese tools used for building the shrines.

Then Maholo took us to the Gekū shrine areas, a few kilometers away, which allow much more access. These shrines, and the bridge that leads to them, are also built on the alternating-site, 20-year cycle. But here you walk on the right, and there are four arches — I could not find out why. Most interesting, however, is that in World War II the Japanese emperor ordered a rare temporary delay in shrine rebuilding. While the people of Ise could not defy him, they realized that he had only mentioned the shrines, so they went ahead and rebuilt the bridge as scheduled in the middle of a war-torn year.

Finally, we headed to the train station, from where Danny and Daniel would travel to Kyoto for their flights, and Maholo would return to Tokyo. Ping and I later boarded the train to Osaka to stay the night, and then headed to Nara prefecture the next day.

Hōryū-ji at Nara

Only 45 minutes by train from Osaka is the stop at Hōryū-ji, a bit before you get to Nara center. Almost concurrent to the building of the first shrine at Ise in the 7th century, a complex of Buddhist temples were built here beginning in 607 CE.

The tall pagoda at Hōryū-ji is one of the oldest continuously standing structures in the world. And while there is controversy over which parts of this temple complex are orginal, the central vertical pillar of wood in the Pagoda was definitively felled in 594.

The architecture has a strong Chinese influence, reflecting the route Buddhism traveled before arriving in Japan, and came with a tradition of continual maintenance rather than periodic rebuilding.

I suspect one of the main reasons these buildings have survived so long is their ceramic roof. The roof tiles can last centuries and are vastly less susceptible to fire than wood or thatch. Like the Shinto shrines, though, no one resides in these buildings, so the chance of human error starting a blaze is vastly diminished. I was amused to see the “no smoking” sign as we entered one of temples.

As you walk through these temples there are many beautiful little maintenance details. Places where water would have wicked into the bottom of a pillar or around the edge of a metal detail have been carefully removed, with new wood spliced back in over the centuries.

It is striking that this part of Japan houses two sets of structures, both of nearly equal age, and both made of largely ephemeral materials that have lasted over 14 centuries through totally different mechanisms and religions. Both require a continuous, diligent and respectful civilization to sustain them, yet one is punctuated and episodic, while the other is gradual. Both are great models for how to make a building, or an institution, last through millennia.

Learn More

- Read Alexander Rose’s recent essay in BBC Future, “How to Build Something that Lasts 10,000 Years.”

- See more photos from Alexander Rose’s trip to Japan here.

- Read Soul of Japan: An Introduction to Shinto and Ise Jingu (02013) in full here.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe