In the 02010s, the animated GIF, for better or worse, took hold as the visual language of internet culture. The ubiquity and increased power of mobile devices enabled users to share animations with ease. And share they did. In 02016, the GIF-sharing site Giphy revealed that its 100 million daily active users sent 1 billion GIFs a day.

While seemingly frivolous, these animations satisfied a real need online: non-linguistic social and emotional cues, difficult to convey in purely text-based communication, could be simply expressed through the visual communication of GIFs.

Many pointed out that the GIF trend hearkened back to earlier periods of history — such as the 01990s, when the GIF format first proliferated the web, or the 01800s, when Eadweard Muybridge, John Hershel, and others experimented with early animation techniques that were a prelude to modern cinema.

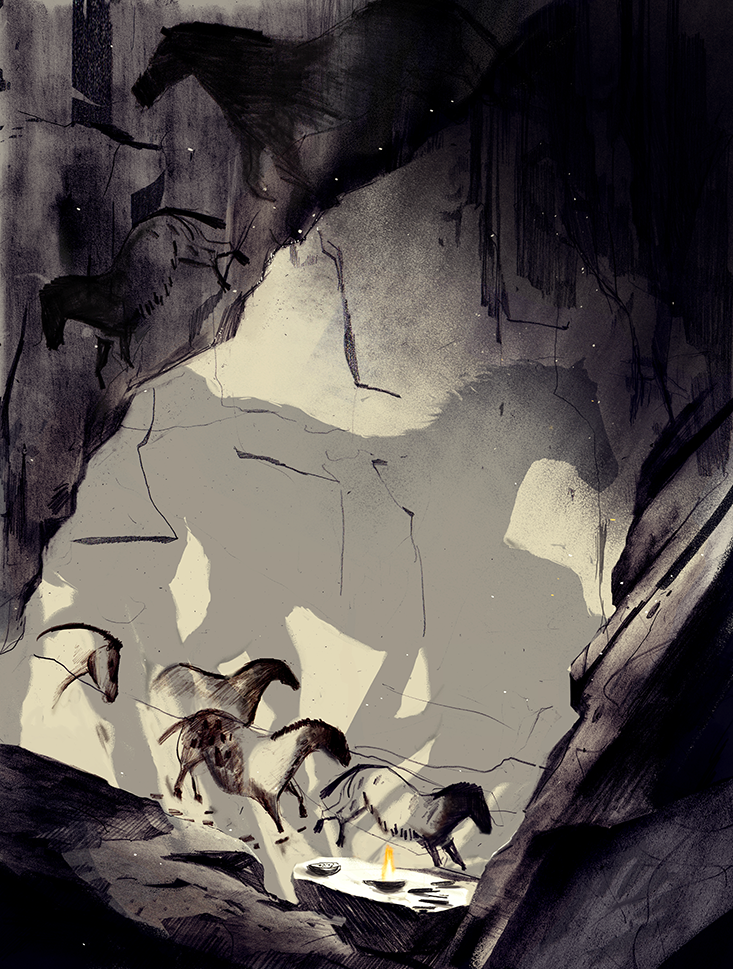

But one can go back even further, all the way to the Stone Age. Marc Azéma, a Paleolithic researcher and filmmaker, claimed in a 02012 paper that the cave paintings found in Lascaux, Chauvet, and other famous Paleolithic caves—the oldest of which were painted 32,000 years ago—were actually early animations:

Palaeolithic artists designed a system of graphic narrative that depicted a number of events befalling the same animal, or groups of animals, so transmitting an educational or allegorical message. They also invented the principle of sequential animation, based on the properties of retinal persistence. This was achieved by showing a series of juxtaposed or superimposed images of the same animal.

The effect of animation was likely achieved, Azéma claims, by the flickering of a lamp as it was moved across the stone wall. To demonstrate the effect, Azéma made a video animating the juxtaposed and superimposed cave painting images.

As science journalist Zach Zorich notes, when Lascaux was discovered in 01940, over 100 stone lamps were found throughout the cave, lending credence to Azéma’s claims. The original placement of the lamps, however, was not recorded.

“At the time, archeologists did not consider how the brightness and the location of lights altered how the paintings would have been viewed,” Zorich writes. “In general, archeologists have paid considerably less attention to how the use of fire for light affected the development of our species, compared to the use of fire for warmth and cooking.”

Some of these paintings, such as the “Grand Panneau” in Chauvet, depicted not only movement, but narrative. As such, Azéma considers them a progenitor of cinema.

To buttress his claims that the cave paintings were intentionally animated, Azéma raises another apparent example of Paleolithic animation. In 01868, archaeologists found a bone disk a little over an inch in diameter in southwestern France. Scholars estimate the disk is between 14,000 to 21,000 years old. Both sides of the disk depict a doe, with one side showing the doe standing, and the other showing it lying down.

Azéma hypothesized that the disk was depicting animation, and created a reproduction to test it out. He passed a string through the hole in the center of the disc, and pivoted it rapidly by pulling both ends of the string. The two images are superimposed on the retina in quick succession, giving the appearance of the animal sitting down and getting up.

“Thus,” writes Azéma, “the Palaeolithic artists invented an optical toy, whose principle was to be found again with the invention of the thaumatrope in 01825, which is itself the direct ancestor of the cinematic camera.”

Archaeologists have tended to interpret artifacts like the spinning disc as ritual or decorative objects, rather than toys. Recent work by scholars such as Kristine Garroway and Michelle Langley has drawn attention to the myriad of artifacts across the world dating back tens of thousands of years that were more likely used for purposes of play than worship.

Like the GIFs of today, these early animations served to entertain while also fulfilling a deeper function. In the case of the cave paintings and the spinning disk, Azéma believes that the depiction of a number of events befalling the same animal or groups of animals “transmitted an educational or allegorical message.”

According to science writer Steven Johnson, even if these animations were simply created for purposes of delight and entertainment, that too would be fulfilling an essential function in the evolution of civilization: activating our sense of interest and delight in the world—which ultimately powers innovation.

“There’s a whole world of seemingly frivolous things that have been part of the human experience for tens of thousands of years that are nonetheless incredibly productive and important to our civilization,” Johnson said in a recent Seminar on Long-term Thinking. “These forms of delight, these forms of play have actually been significant drivers of change and of progress in society.”