Lessons From a Trip Back in Time

The rapid rate of technological change is a common topic of discussion these days, but only occasionally does someone actually take the time to examine – let alone utilize – the technologies that we so readily leave behind.

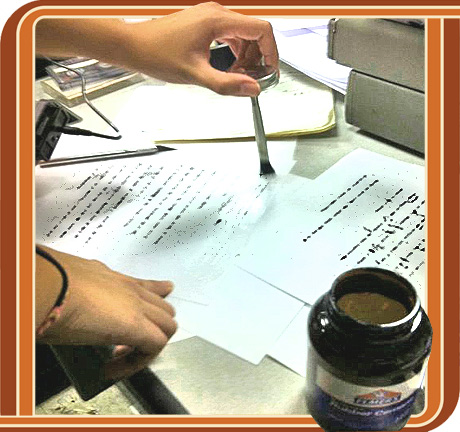

A great example of just such an undertaking is a project called All On Paper recently carried out by student journalists at Florida Atlantic University. Under the direction of Michael Koretzky, president of the South Florida Pro Chapter of the Society for Professional Journalists, the staff at the student newspaper University Press produced an entire issue using decades-old newsroom methods. For a week, typewriters, film photography, x-acto knives and rubber cement took the place of Word, Photoshop and InDesign.

Koretzky shared some of the challenges and lessons from the experience on his blog, journoterrorist. As he and other professionals taught the students how to use old technology, they realized that even they had to occasionally reference the user’s manual.

While archaeologists try to recreate what life was like 10,000 years ago, and historians try to recreate what life was like 1,000 years ago, journalists can’t even recreate how they published a newspaper 20 years ago. No one documented the details or saved the old equipment. (I had to buy some of it from creepy old men through Craigslist.)

Journalists may write history’s first draft, but when it comes to covering their own history, they don’t even take notes.

Journalists, of course, aren’t the only ones who have neglected their abandoned methodologies. Neither, however, are they the only ones who have attempted to get back to basics. A previous post on this blog featured an artist who, in fact, specializes in such undertakings, and Long Now executive director Alexander Rose maintains a list of projects that record humanity and technology in ways that could help restart civilization in the event of some sort of collapse.

Koretzky ends his description of All On Paper with a quote from one of the participants. It is a statement of appreciation, and one that highlights a potential benefit of placing our current technologies in their historical context.

Technology hasn’t made us lazier, but it has made it possible to be lazier while still producing the same amount of quality work. Now that I’ve realized this, I know I’ll definitely be working faster to produce more quality news. And unlike the ancient civilizations of the 20th century, I’ve got the technology to do it.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe