Our knowledge of the past is inherently imperfect. With every passing moment, information about the present fades and is lost as it recedes into the expanses of memory, never to be recalled. That doesn't mean that there's no point in trying to learn about our history, to expand the corpus of knowledge we have reclaimed from the entropic force of forgetting — but it does mean we have to be aware of our limits when we attempt to gain understanding from the past.

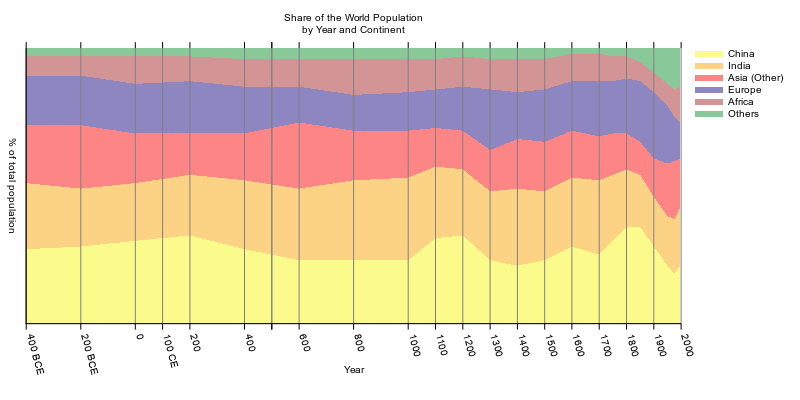

One such area where the gaps in the historical record can be felt most acutely is in the challenge of historical population estimation. It's difficult to know what the population of any given country was 1,000 or even 500 years ago, but using the data we have — a scattered assemblage of censuses, birth and death records, and other fragments of early bureaucracy — we can start to get a sense of these populations.

In the broad, interdisciplinary pursuit of historical population estimation, one of the most heavily-cited works is Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones' Atlas of World Population History. First published in 01978, McEvedy and Jones' reference book aims to show the population history of nearly every country in the world from 400 BCE to what was then the present day. Their estimates have been used as an underlying source for a wide variety of academic research, from papers on "Long-term Population Cycles in Human Societies" to examinations of the "Cultural Evolution of Love in Literary History" to the History Database of the Global Environment, widely used as a tool in long-term global climate change studies.

Where McEvedy and Jones' work has perhaps seen the most use, though, is in the field of developmental economics. Works by acclaimed scholars like Daron Acemoğlu and Oded Galor lean heavily on their estimates, using them as the underlying data that informs further analysis of economic development in different states and regions over the course of centuries or even millennia.

The only problem: McEvedy and Jones' data is wrong.

That's the contention of Yale economic historian Timothy Guinnane, who published an article in August in the Journal of Economic History titled "We Do Not Know the Population of Every Country in the World for the Past Two Thousand Years." Professor Guinnane's article is a well-argued analysis of the flaws in McEvedy and Jones' data as well as the compounding mistakes found in many of the papers that use it. But you don't have to take his word for it. Instead, take McEvedy and Jones' own word — they conclude the introduction of the Atlas by offering a mea culpa:

"We haven’t just pulled figures out of the sky."

"Well, not often."

“No Such Data Exist”

Most societies before, say, 01850 did not keep the kind of high quality records of population that modern censuses provide. After the remarkably comprehensive Domesday Book was completed by King William I's royal administration in 01086, England would not be surveyed and censused in full for another 700 years. In the gaps between these moments of clarity, researchers in demographic and economic history must make extrapolations and approximations either by using birth, death, and migration records going backwards from a known point in order to find earlier populations, using patterns from countries with better records to take a stab at the data for more obscure neighbors, or building rough estimates of population based on proxy with values like GDP.

All of this, Guinnane told me in an interview, is something that McEvedy and Jones make note of in their own work. The assumptions made in their Atlas are not particularly egregious — especially relative to the 01970s, the era in which they compiled their work. The problem, though, comes in the myriad authors that have cited McEvedy and Jones in the decades that have followed.

Guinnane was inspired to write his article after seeing scholar after scholar make “references to data of this type”, which “baffled” him — his own experience as an economic historian indicated that “no such data exist.” As he looked more deeply into the uses and misuses of McEvedy and Jones, he found reason to think that the two authors would too be "baffled" to see modern developmental economists using their dataset in the ways that they have, in part because, as his paper notes, "researchers have provided better figures in the past 40 years" in many regions.

An Ouroboros of Misestimation

Yet the missteps that Guinnane catalogs in his paper are deeper than just using out-dated figures. In many of the papers that he cites, Guinnane found methodological flaws that exacerbated the existing problems with McEvedy and Jones' estimates. One especially prevalent flaw related to an assumption in statistics known as “classical measurement error.” Without going too far into the weeds of statistical analysis, measurement error is considered “classical” when it is independent of the true value being measured or any other values in the model and their respective errors. Economists frequently assume that their measurement errors are classical, and from there assume that those errors affect their estimates in certain predictable ways.

However, McEvedy and Jones use estimates with measurement errors that are clearly not classical. Their estimates for each country’s population at each particular time are all rounded with differing levels of precision: estimates under one million people are rounded to the nearest hundred thousand, while estimates over 1 billion are instead rounded to the nearest 25 million. This means that the magnitude of the error for any given estimate is directly correlated to the size of the estimate itself.

Another source of trouble comes from a more theoretical problem with using McEvedy and Jones’ data. The Atlas frequently based its population estimates on economic data on a given country or region — saying, for example, that Poland in 01350 had an economy of size Y able to support X people. Yet many subsequent researchers have used McEvedy and Jones’ economically-derived estimates of population to derive new estimates of economy size, creating what amounts to an ouroboros of misestimation — or, in the terms of art of econometric modeling, a problem of “circularity”. Some estimate of the economy of Poland in 01350 is used to estimate its population, which is then, decades down the line, used to further guess at the characteristics of its economy. In the end, as Guinnane told me, “all you get back from the econometric model is the assumption [McEvedy and Jones] made in the first place.”

But beyond observing these particular missteps, Guinnane wrote the paper to point to a broader philosophical problem in how we grapple with historical uncertainty. While he cites individual papers that use, in his view, McEvedy and Jones’ data in more or less thoughtful ways, he’s not trying to assign blame to individual scholars. Instead, he told me, the problem was that “so long as influential and prestigious journals in economics accept research based on things like [the Atlas], we will not get better estimates of population in the past.”

In his view, “estimates will not improve unless we care enough about good data to stop naively using the old. And if there are times and places for which we really have no more than guesses, we have to accept that econometric analysis of guesses is not going to lead to the truth.”