Colonel Matthew Bogdanos Seminar Primer

When we think of the awful consequences of war, the deaths of the soldiers and civilians always remind us that futures have been destroyed – the young man who will never raise a family, or the one-year-old daughter who will never know her father. But war in the third millennium AD has brought us an entirely new and different horror – the destruction of an entire past. What [took] place in southern Iraq [after the American invasion] is nothing less than the eradication of the material record of the world’s first urban, literate civilization. (Gil Stein, Catastrophe! The Looting and Destruction of Iraq’s Past)

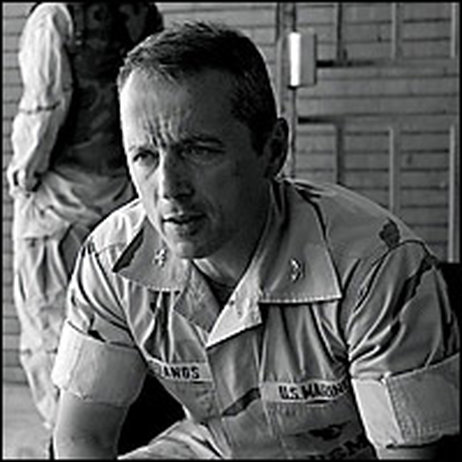

Scholars had had a premonition that the war in Iraq would bring looters to the National Museum in Baghdad, home to the world’s largest collection of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts; several Iraqi museums had been plundered during the Gulf War of the early 01990s. Nevertheless, they were powerless to stop it from happening again. In April 02003, mere days after American troops first entered Baghdad and most of the museum staff had sought safety at home, bands of looters forced entry into the galleries and took nearly 15,000 artifacts. US Marine Colonel Matthew Bogdanos had just arrived in Iraq when he heard the news. A career prosecutor with a deep personal interest in ancient civilizations, he headed straight for the capital to launch an investigation and large-scale recovery effort.

Growing up in lower Manhattan as the child of Greek immigrants, Bogdanos first became interested in the Classical world when his mother handed him a copy of Homer’s Iliad at the age of twelve. The military encouraged him to pursue this interest further: he obtained a Master’s in Classics, as well as a law degree, while training to become a Marine Corps officer. Indeed, Bogdanos feels that a military career and intellectual pursuits are natural extensions of one another. As he explained in a 02009 opinion piece for the Washington Post,

Growing up in lower Manhattan as the child of Greek immigrants, Bogdanos first became interested in the Classical world when his mother handed him a copy of Homer’s Iliad at the age of twelve. The military encouraged him to pursue this interest further: he obtained a Master’s in Classics, as well as a law degree, while training to become a Marine Corps officer. Indeed, Bogdanos feels that a military career and intellectual pursuits are natural extensions of one another. As he explained in a 02009 opinion piece for the Washington Post,

… British general Sir William Butler warned a century ago [that] “A nation that will insist upon drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards.” It was not always so. We praise classical Greece for philosophy, art and democracy. Yet Athenians knew Socrates, the father of philosophy, for his bravery on the battlefield and Xenophon, author of the epic “Anabasis,” for his generalship. Aeschylus, antiquity’s greatest tragedian, wrote his own epitaph: “This gravestone covers Aeschylus … The field of Marathon will speak of his bravery.” In our time, a steady aggrandizement of self at the expense of society has forced the warrior culture and its ideals to the margins as antique refinements, like knowing classical languages. Yet the most cherished ideal – arête, the classical Greek concept of honor – is anything but passe. Just as “Semper Fidelis” (always faithful) is not merely the Marine Corps motto but a way of life, so is honor a form of mental conditioning – a force-multiplier: Decide in advance to act honorably, and you know without hesitation what to do in a crisis.

Upon resigning from active duty in 01988, Bogdanos joined the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, where his sense of duty and tenacious investigative skills earned him the nickname “pit bull.” Pop culture will remember him best as the prosecutor who failed to convict Sean “P. Diddy” Combs for a 01999 club shooting.

After the Al Qaeda attack of September 11, 02001, Bogdanos was called back to active duty with the Marine Corps. After a brief tour in Afghanistan he was deployed to Iraq, where he was asked to investigate terrorist funding and banned weapons. He had just arrived in Basra when a question from an angry journalist alerted him to the looting at the National Museum in Baghdad. Realizing that its facilities housed a priceless and unique record of the world’s oldest civilization, Bogdanos felt duty-bound to take action. He recalls:

Here I was in Basra, I had the only law enforcement, counterterrorism team that the U.S. Government had in-country. This was a criminal investigation. And we also had enough firepower to at least secure the museum. So I simply decided this was our mission. I know sometimes I get painted as this maverick Marine colonel, but one of the things the Marine Corps instills in you is a seize-the-initiative mentality. It is a Marine Corps philosophy that it is better to beg for forgiveness than ask for permission. So, what I was not going to do was file a request in triplicate in order to go to the museum.

The plundering and destruction of artifacts had begun only days after troops first entered Baghdad. A few remaining members of the museum’s staff had done what they could to safeguard its holdings, but were unable to protect the premises on their own. The looters included professional thieves, but also others – local residents, even government officials and some museum staff, who knew where to find the most valuable objects. Forty artifacts were stolen from the public gallery; more than 13,000 were lifted from the building’s storage rooms and basement.

Scholars had anticipated the war’s destructive impact on the vast collections of ancient ruins and artifacts in Iraq – once the heart of Mesopotamian civilization. Many had spent the months leading up to the invasion in painstaking efforts to document whatever objects and remains they could, hoping to preserve at least a record of what had been there. This would prove helpful in Bogdanos’ mission to recover the looted artifacts. The public availability of records on these items made it difficult for looters to unload them through the antiquities trade – an illegal market that would not only help objects disappear, but also provide a significant source of funding for the insurgency in Iraq. Bogdanos collaborated with scholars at the Oriental Institute in Chicago to create an online catalog of all artifacts that had been taken from the National Museum. In the years since 02003, this database has facilitated the recovery of many artifacts. Many more, however, remain to be found.

… we’re talking about our history, our heritage, our cultural beginnings. … those who do not remember the past are destined to repeat its mistakes. The past is what we have. It’s what we bring with us into the future. I can’t imagine a more important undertaking. (PBS News Hour)

Colonel Matthew Bogdanos received a national humanities medal for his work and wrote a book about the effort. He will discuss the investigation and the continuing, global search for lost artifacts, at the SF JAZZ Center on February 24. You can reserve tickets, get directions, and sign up for the podcast on our Seminar page.

Because this Seminar revolves around and discusses specifics of an ongoing investigation, there will be no recording of any kind. If you are unable to attend in person but would like to know more about Bogdanos’ work, you can read more in his book, Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine’s Passion to Recover the World’s Greatest Stolen Treasures. Thank you for your understanding.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe