A 240-Year Old Programmable Computer Boy

In the late 18th century, Swiss clock- and watchmaker Pierre Jaquet Droz decided to advertise his business by building three automata, or mechanical robots, in the shape of young children. Still functional after almost 240 years, the machines are a marvel of mechanical engineering. “The Musician” is a girl who plays an organ – her eyes follow her fingers as they press down on the instrument’s keys, and her chest moves up and down in a breathing motion. “The Draftsman” is a boy who draws four different images – including a portrait of Louis XV.

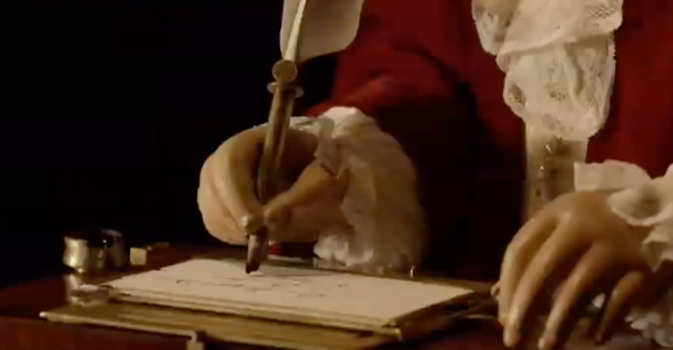

The most complex of the three, however, is “The Writer.” Constructed with nearly 6,000 components, this mechanical boy sits at a small desk and uses a goose feather quill to write sentences on a piece of paper. Like his Draftsman brother, the Writer’s three-dimensional arm movements are coded by a series of cams: they direct his arm to an inkwell, into which he dips his quill, and then back to his paper, where he writes out letters in a neat cursive script. Professor Simon Schaffer, host of the BBC4 documentary Mechanical Marvels: Clockwork Dreams, explains:

As these cams move, three cam followers read their shaped edges and translate these into the movement of the boy’s arm. Working together, the cams control every stroke of the quill pen, and exactly how much pressure is applied to the paper, so as to achieve beautiful, elegant, and fluid writing. With this sublime machine, Jaquet Droz had reverse-engineered the very act of writing.

But the mechanical boy contained one perhaps even more astonishing feature. The wheel that controlled the cams was made up of letters that could be removed, and then replaced and reordered. These allowed the writer in principle to make any word and any sentence. In other words, it allowed the writer to be programmed. This beautiful boy is thus a distant ancestor of the modern programmable computer.

The Writer is an early example, too, of some of the mechanical technology that runs the 10,000 Year Clock. Of course, the Writer’s system is entirely analog, whereas the Clock incorporates both analog and digital mechanisms (the serial bit adders at the heart of the Orrery provide a binary input for its simulation of planetary movement). Nevertheless, the 18th century automaton is a miniature testimony to what the Clock exemplifies on monument scale: that mechanical systems possess the elegance, the transparency, and the functionality needed to endure across long stretches of time.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe