Whole Earth Psychology

Anyone who has traveled abroad or simply eaten at the ethnic restaurant around the corner will appreciate the richness of cross-cultural diversity our world has to offer. Each part of the world has its own cuisine, its own social organization, its own religious practices, and its own fashions. Cognitive research has always assumed that underneath this incredible diversity, humans nevertheless all have the same basic wiring: even if we believe in different things, we ultimately possess the same cognitive skills and respond to external stimuli in similar ways.

Anthropological research, however, suggests that culture reaches much further down into our brains. In a recent feature for the Pacific Standard, Ethan Watters suggests that

The most interesting things about cultures may not be in the observable things they do – the rituals, eating preferences, codes of behavior, and the like – but in the way they mold our most fundamental conscious and unconscious thinking and perception.

In the early twentieth century, anthropologists realized that culture affects not just the way we behave, but also the way our mind engages with the world. Inspired by developments in psychoanalysis, these scholars began to explore how personality and psychological functioning are shaped by the cultural environment. Margaret Mead, for example, famously argued that the experience of adolescence on Samoa bears little resemblance to what we know of American teenagers, debunking the assumption that the wrought experience of puberty is the result of purely biological factors. A few decades later, Robert Levy and Jean Briggs showed that culture affects the way we experience and express emotion; and the work of scholars like Mel Spiro and Rick Shweder has stimulated research on how the human sense of self is shaped by the cultural environment.

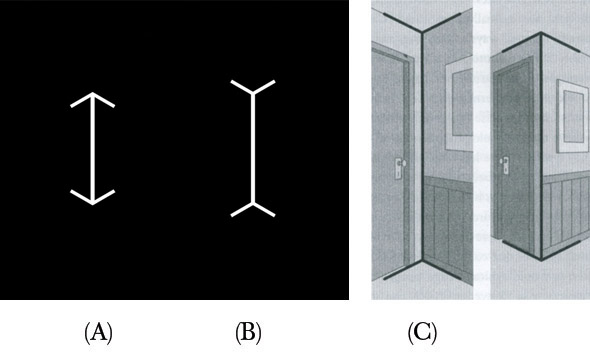

Watters features the more recent work of anthropologist Joe Henrich, who took this line of scholarship a step further by combining ethnographic work with cognitive research methods. In 02010, he co-authored an article in which he showed that responses to classic cognitive tests (such as the Müller-Lyer Illusion) in fact vary across cultures. In other words: even the human modes of reasoning and perception that we believed to be universal are in fact uniquely shaped by our cultural environment.

Cognitive skills, Henrich and his colleagues argue, are not hardwired into our brains at all: there is considerable cross-cultural variation in the way we respond to and make sense of environmental stimuli. We develop these divergent cognitive styles because the worlds we grow up in vary so widely from one another. Think of the vast differences between the world of lower Manhattan, say, and a remote village in the Himalayan mountains; or between a capitalist society and a socialist state. A New Yorker’s perception of lines, colors, and distances will differ considerably from that of a Nepali, just as a Frenchman and a North Korean may not agree about the definition of “fairness.” Though we are all born with the same brain, that soft tissue is shaped by our environment as we develop our cognitive capacities and socialize into our community. And that environment is inevitably, indelibly shaped by the culture of which we are a part. Like language, we might think of culture as an “encapsulated universe.”

Henrich’s research unsettles decades of cognitive research, and not just because it debunks the idea of a universal pattern of human functioning. As it turns out, the particular population commonly studied by psychologists and economists lies at the very edges of the “human bell curve.”

Economists and psychologists, for their part, did an end run around the issue with the convenient assumption that their job was to study the human mind stripped of culture. The human brain is genetically comparable around the globe, it was agreed, so human hardwiring for much behavior, perception, and cognition should be similarly universal. No need, in that case, to look beyond the convenient population of undergraduates for test subjects. A 2008 survey of the top six psychology journals dramatically shows how common that assumption was: more than 96% of the subjects tested in psychological studies from 2003 to 2007 were Westerners – with nearly 70 percent from the United States alone. Put another way: 96 percent of human subjects in these studies came from countries that represent only 12 percent of the world’s population.

Henrich and his colleagues refer to this population of college students as WEIRD – not only because they happen to be Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, but also because this population turns out to be such an outlier. Henrich’s research proves that American modes of perception are not the rule, but a radical exception to it. Watters writes:

It is not just our Western habits and cultural preferences that are different from the rest of the world, it appears. The very way we think about ourselves and others – and even the way we perceive reality – makes us distinct from other humans on the planet, not to mention from the vast majority of our ancestors. Among Westerners, the data showed that Americans were often the most unusual, leading the researchers to conclude that “American participants are exceptional even within the unusual population of Westerners – outliers among outliers.” Given the data, they concluded that social scientists could not possibly have picked a worse population from which to draw broad generalizations. Researchers had been doing the equivalent of studying penguins while believing that they were learning insights applicable to all birds.

Watters suggests that it may be one of those uniquely Western psychological features that led us to believe that our cognitive functioning is free of culture. Looking upon ourselves as free and autonomous individuals, we’ve come to assume that while we may live inside a culture, our essence somehow exists beyond – and independently of – its bounds.

Not only does Henrich’s research argue that we are not as free of culture as we had believed; his research shows that a true understanding of human psychology – and even of brain functioning – must always take a larger view, and reach beyond the familiarity of our own immediate environment.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe