Three Major Installations (and an impending opening?) by James Turrell

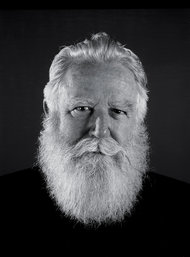

Artist James Turrell, though generally somewhat elusive and inclined towards private commissions, has had a big summer, as reported by the New York Times in June. Major installations by Turrell have been featured in New York, Houston and Los Angeles. The first two end this month, while the latter runs through April of 02014.

His work focuses on light and perception and the full experience often requires a viewer to spend more than a passing glance. That’s because it can take the human eye up to 45 minutes to fully adjust to a dark room and many of Turrell’s installations make use of such subtle light effects that patience is required to even see what he’s done. The large scale and precise requirements of his work make this summer’s nationwide availability of it an unprecedented opportunity.

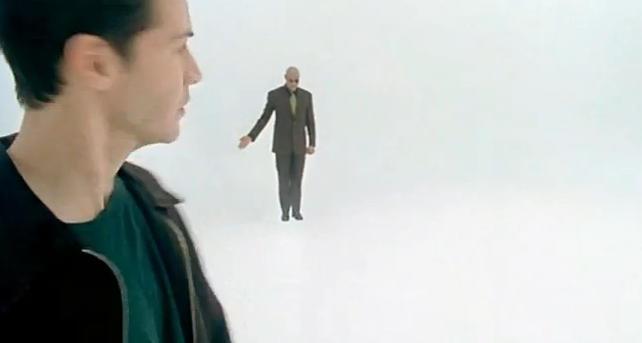

Turrell’s immersive installations create spaces not unlike the scenes in The Matrix where characters discuss their world’s central illusion – except in place of Neo’s and Morpheus’s colorless void, Turrell offers a world of color.

In other pieces, he creates Skyspaces – open roofed rooms with carefully calibrated ceilings and lights that seem to bring the sky down, to give it texture and to make it appear material.

He’s also known for the mythic Roden Crater, an extinct volcano he bought in 01977. Since then, work at the site has been aimed at creating a naked-eye observatory using principles of light and perception similar to his more accessible installations, but cosmic in scale. An ever more prevalent element of the mythos of the project is the question of when it will be done. Few have seen it as it’s come together over the decades, but the author of Turrell’s recent New York Times profile was able to explore and discuss Roden Crater in depth:

One by one, we walked up the tunnel. It was 854 feet long and 12 feet in diameter, with blue-black interior walls and ribs protruding every four feet. At the top, a great white circle of light beamed toward us. Or so it seemed. As we drew closer, the color changed from white to blue, and the shape began to shift, elongating from a circle to an oval and rising overhead, until it was clear that what had seemed to be a round opening at the far end of the tunnel was in fact an elliptical Skyspace in a large viewing room. A long, narrow staircase made of bronze ascended through it.

We climbed onto the top of the crater and stepped into the sun. Once again we were surrounded by a Martian landscape of crushed red stone. A cold wind blew across the caldera, and we lay down to view the sky, the clouds streaking overhead as the heavens vaulted.

Dusk was coming. We got up and followed a narrow ramp into another Skyspace. It was round, with a narrow bench around the perimeter. Turrell calls it “Crater’s Eye.” We took seats on the bench and stared through the opening in silence. The color of the sky was deepening. It was rich with blue and darkness. It seemed to hover on the ceiling close enough to touch. No one spoke for 30 minutes. I glanced over at Turrell. His hands were folded in his lap, his eyes smiling at the sky. Whatever else the crater had become for him — a job, a dream, an office, a persistent reminder of his own mortality — it was clear that the Skyspace still had the power to lift him up from earth.

Turrell may, it seems, reward patience like few artists can.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe