Slow art

art:21, a recent PBS documentary series on contemporary art and artists, featured an episode on works dealing innovatively with time, which I saw on DVD over the weekend. Among those profiled was Paul Pfeiffer (born in Honolulu, 01966) a video artist who now lives and works in New York City.

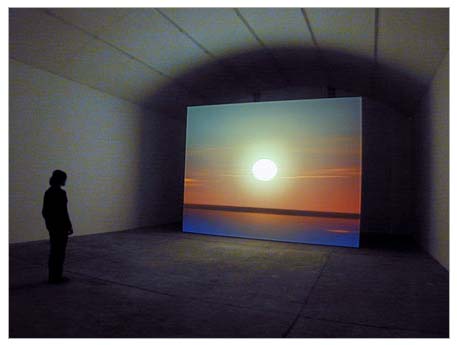

His work entitled “Morning After the Deluge” (after a Turner painting) is a twenty-minute loop of a flawless Cape Cod sunrise and sunset, edited together such that the sun itself remains fixed centre-screen, while the horizon appears to move across it.

Image from carlier | gebauer

Pfeiffer makes some interesting remarks on the piece in a 02004 article entitled “The Sun is God“:

I shot Morning After The Deluge in real time. I was interested in the idea that the video loop represents a disturbing notion of time being something that you can actually freeze. When you look at the image you don’t see anything happening. The sun and the horizon don’t seem to move. You might think it’s a still unless you happen to look at it at a moment when a bird is flying by.

In the art:21 show (of which streaming video extracts are available online at PBS), he notes:

These days, it’s quite idealistic to think of the viewer as being anything but distracted, given the kind of image-saturated world that people function in.

In “Morning After the Deluge”, you have to be there at least for a few minutes, if not for the full twenty minutes, to see the full loop and to get the full sense of the sun rising and setting. In a way, it’s not very viewer-friendly. The shot is in real time, it almost looks like nothing’s happening, you really have to stand for a while to get the sense that the sun is slowly setting and rising. In the meantime, though, there’s a lot of other action that’s happening on a much smaller scale. You have birds flying very quickly through the screen. It’s almost at a pixel level, barely there at all — but projected big, this is something that you get to see. So this is maybe what you enter in on as a moving image, but as you sit with it for a while longer, then the bigger movements become accessible to you.

This makes for an interesting comparison to Brian Eno’s 77 Million Paintings, which was recently hosted by Long Now and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. In a Wired interview from last week, Eno says:

It strikes me as one of the most interesting things about these shows is not one of the most immediately visible. One of the strangest experiences you’ll be having is an experience of time in a different way. You’ll see people rushing in off the street and they’re all busy and their body language is hectic — a “show me what’s happening” kind of language. And you watch them gradually settling down and start to slow down to the pace of the work, which is very slow. People seem really, really grateful for this possibility.

Pfeiffer challenges his distracted, image-saturated viewer to tune in to the real-time pace of a day beginning and ending, and Eno draws in crowds and keeps them for hours at a time with a mesmeric unfolding of practically endless visual (and musical) possibilities. Two very different approaches, but both are experiences intended to elicit and reward patient, sustained attention. This is an interesting development; perhaps part of a broader aesthetic backlash also including the Slow Food movement? For in the visual arts, a field of endeavour where it seems increasingly difficult to capture interest with conventional shock tactics, that which demands a certain kind of careful attention — which decelerates — may be some of the most daring artwork of all.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe