Five New Discoveries Offer an Opportunity to Contemplate the Difference Between the Dead and Merely Dormant

If life and death are ultimately separated only by the paces at which processes at which the many layers of biology align, the future seems like it will be a twilight zone

Although the sensitive can feel it in all seasons, Autumn seems to thin the veil between the living and the dead. Writing from the dying cusp of summer and the longer bardo marking humankind’s uneasy passage into a new world age (a transit paradoxically defined by floating signifiers and eroded, fluid categories), the time seems right to survey five new discoveries from paleontology, zoology, and neuroscience that offer up an opportunity to contemplate the difference between the dead, and merely dormant.

We start 125 million years ago in the unbelievably fossiliferous Liaoning Province of China, one of the world’s finest lagerstätten (an area of unusually rich floral or faunal deposits — such as Canada’s famous Burgess Shale, which captured the transition into the first bloom of complex, hard-shelled, eye-bearing life; or the Solnhofen Limestone in Germany, from which flew the “Urvogel” feathered dinosaur Archaeopteryx, one of the most significant fossil finds in scientific history). Liaoning’s Lujiatan Beds just offered up a pair of perfectly-preserved herbivorous small dinosaurs, named Changmiania or “Sleeping Beauty” for how they were discovered buried in repose within their burrows by what was apparently volcanic ash, a kind of prehistoric Pompeii:

There’s something especially poignant about flash-frozen remains that render ancient life in its sweet, quiet moments — a challenge to the reigning iconography of the Dawn Ages with their battling giants and their bloodied teeth. Like the Lovers of Valdaro, or the family of Pinacosaurus buried together huddling up against a sandstorm, Changmainia makes the alien past familiar and reminds us of the continuity of life through all its transmutations.

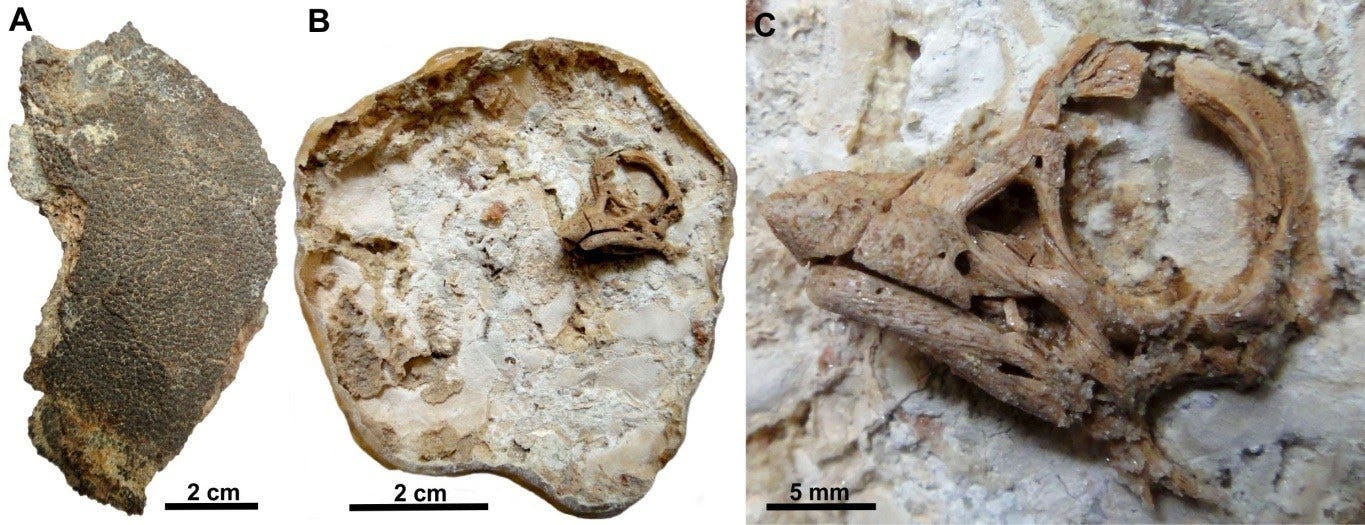

Similarly precious is the new discovery of a Titanosaurid (long-necked dinosaur) embryo from Late Cretaceous Patagonia. These creatures laid the largest eggs known in natural history — a requisite to house what would become some of the biggest animals to ever walk the land. Even so, their contents were so small and delicate it is a marvelous surprise to find the face of this pre-natal “Littlefoot” in such great shape, preserving what looks like an “egg tooth”-bearing structure that would have helped it break free:

From ancient Argentina to the present day, we move from dinosaurs caught sleeping by fossilization to the “lizard popsicles” of modern reptiles who have managed to adapt to freezing night-time temperatures in their alpine environment. Legends tell of these outliers in the genus Liolaemus walking on the Perito Moreno glacier, a very un-lizard-like haunt; they’re regularly studied well above 13,000 feet, where they may be using an internal form of anti-freeze to live through blistering night-time temperatures. The Andes, young by montane standards, offer a heterogeneous environment that may function like a “species pump,” making Liolaemus one of the most diverse lizard genuses; 272 distinct varieties have been described, some of which give live birth to help their young survive where eggs would just freeze solid.

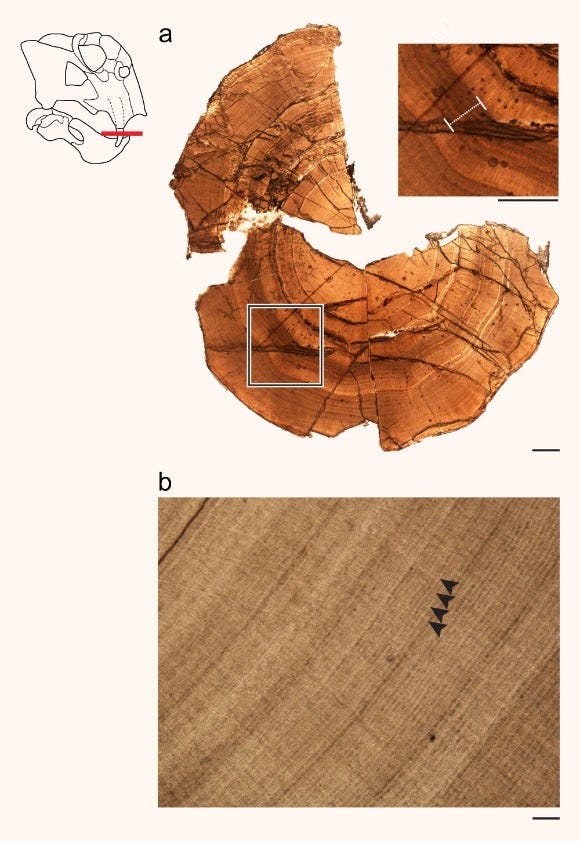

Even further south and further back in time, mammal-like reptile Lystrosaurus hibernated in Antarctica 250 million years ago — a discovery made when examining the pulsing growth captured in the records of ringed bone in its extraordinary tusks, much like the growth rings of a redwood:

This prehistoric beast, however, lived in a world predating woody trees. Toothless, beaked, and tusked, its positively foreign face nonetheless slept through winter just like modern bears and turtles…which might be why it managed to endure the unimaginable hardships of the Permo-Triassic extinction, which wiped out even more life than the meteor that killed the dinosaurs 135 million years later. Slowing down enough to imitate the dead appears to be, poetically, a strategy for dodging draft into their ranks. And likely living on cuisine like roots and tubers during long Antarctic nights, it may have thrived both in and on the underworld. Lystrosaurus seems to have weathered the Great Dying by playing dead and preying on the kinds of flora that could also play dead through a crisis on the surface.

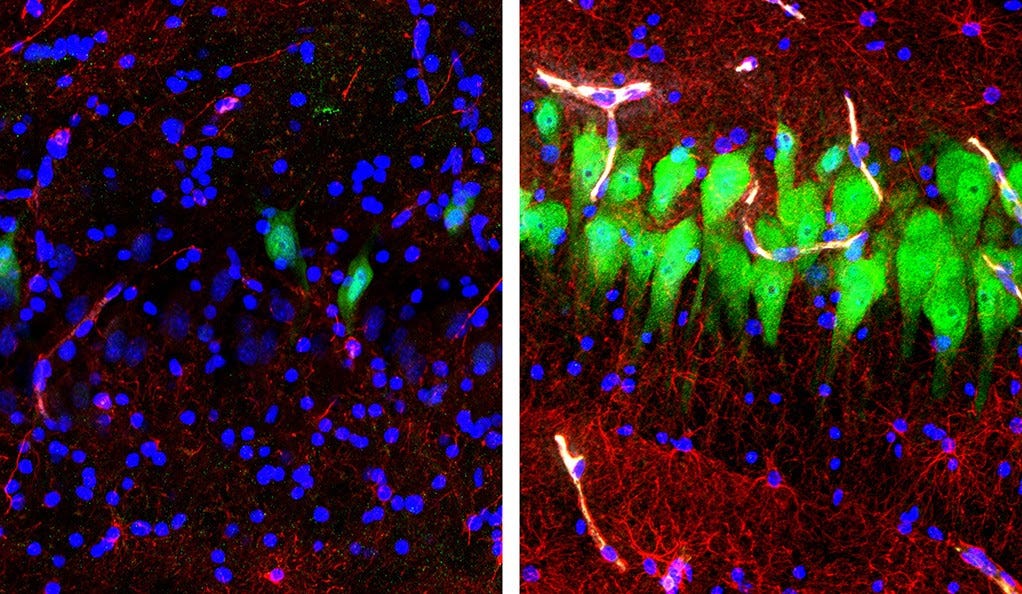

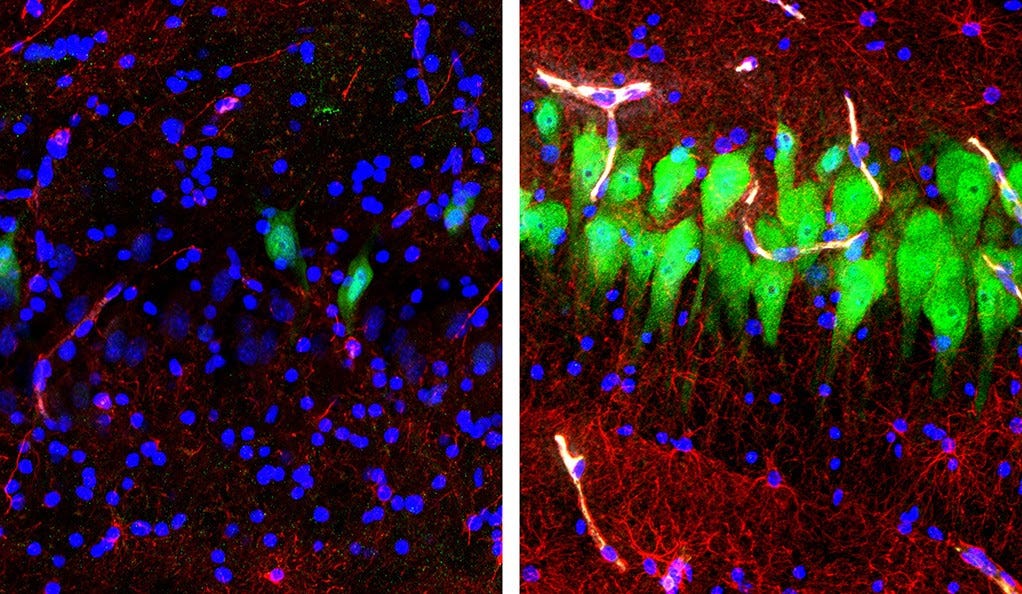

And while we’re on the subject of the blurry boundary between the worlds of life and death, Yale University researchers recently announced they managed to restore activity in some parts of a pig’s brain four hours after death. In the 18th Century when the first proto-CPR resuscitation methods were invented, humans started adding horns to coffins so the not-quite-dead could call for help upon awakening, if necessary; perhaps we’re due for more of this, now that scientists have managed to turn certain regions of a dead brain back on just by simulating blood flow with a special formula called “BrainEx.”

At no point did the team observe coordinated patterns of electrical activity like those now correlated with awareness, but the research may deliver new techniques for studying an intact mammal brain that lead to innovations in brain injury repair. Discoveries like these suggest that life and death, once thought a binary, is a continuum instead — a slope more shallow every year.

If life and death are ultimately separated only by the paces at which processes at which the many layers of biology align, the future seems like it will be a twilight zone: a weird and wide slow Styx akin to Arthur C. Clarke’s 3001: The Final Odyssey, rife with de-extincted mammoths and revived celebrities of history, digital uploads and doubles and uncanny androids, cryogenic mummies in space ark sarcophagi — and more than a few hibernating Luddites waiting for a sign that it is safe to re-emerge.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe