Fandom Relics and the Enthusiastic Past

Fandom memory offers a lens through which to understand the challenges of knowledge preservation between generations and across technologies.

Fandom, in 02022, is big business. Corporations court it, social media platforms are dominated by it, and a large proportion of Gen Z participates in it. It is a lens through which many of the most controversial movements of the last decade can and have been viewed: Gamergate, the alt-right, the Depp v. Heard trial. It’s “a history-shaping force that we’d be foolish to ignore,” and the source of much of contemporary culture’s most fervent and fertile outpourings.

But it didn’t come out of nowhere. Like any subculture it has origins; a history; an evolutionary tree full of hairpin turns, dead ends, and forgotten curiosities. Fandom is often the first to take up new technologies, and develop new and creative ways to express itself. But in moving so quickly, especially in the social media age, it has a tendency to forget itself. Generation gaps can yawn in between different “eras” of fandom, causing even the recent past to fall into darkness — a darkness which every so often receives a flash of illumination.

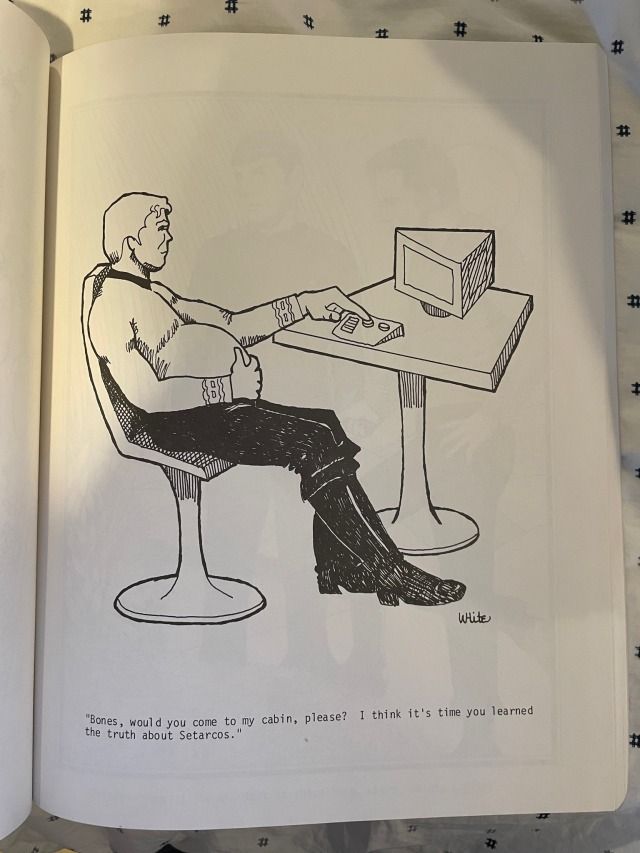

In May 02022, Tumblr user gar-trek posted about a thrift store discovery: “never forget when i found a random star trek zine at the antique store and there was kirk mpreg in it and i was like ’excuse me’ and when i looked up the zine on google it was like ‘includes what could be the first-ever instance mpreg fanart!!’ like why do i own the first ever mpreg fan art ever made. why.” The art depicts a heavily pregnant Captain Kirk speaking to Spock, referencing a well-known slash (male/male) fanfiction story of the era. The response on Tumblr to the discovery was rapturous: many a reply asserted something along the lines of “I don’t even like mpreg, but this is so important.”

Another post about a piece of early piece of fanart depicting Kirk, Spock, and Bones in a three-way relationship (also known as an OT3) from the 01970s also discovered in a thrift store brought up similar emotions amongst the general fandom audience on Tumblr. Even those who claimed not to be Star Trek fans or to not care about the show commented on how they were affected by the discoveries. And user undeadhousewife was moved to muse, “I am legitimately curious what modern fandom would even look like with out Star Trek.”

It’s true that Star Trek forms a major basis of most of what fan studies scholars would consider the world of “Western media fandom” — that amoebic grouping of fan culture that can be traced back to 01970s hand-copied zines and in-person conventions, centering around American and British television shows like Starsky & Hutch, The Professionals, and Blake’s 7. These communities went digital in the 01990s and eventually merged with other types of fandoms in the melting pot of the internet — pop music fandom, Japanese media fandom, science-fiction literature fandom, among others.

There’s a regrettable tendency amongst teenagers in fandom to assume that the fandom switch inside your head will just “turn off” when you hit a certain age. But any fan in their 30s, 40s, or 50s could tell you that’s not the case. If you’re a Star Trek fan, you probably know this, thanks to the fandom’s longevity and continuity, which is helped along by fans who remember the early days and wish to make sure others remember too. Fandom Grandma, a.k.a. Dee, a woman in her late 70s, took the time to share stories of her early days in 01960s Star Trek fandom via Tumblr before she passed away in 02018. She was mourned widely by Tumblr users who treasured her tales of the first slash fiction zines and the time Leonard Nimoy came to a fan club meeting.

But if a fan isn’t part of a fandom like Star Trek or those mentioned above, with histories that stretch back past the digital age, it’s not particularly likely that any given fan is aware of what their fannish forerunners were up to. While it used to be common practice to befriend fans much older than you, who could be resources to learn about fandom history (that is to say, history of your fandom in particular as well as fandom in general), that’s not as frequently the case today. It’s easy to spot fans on Twitter under the age of 18 with “23+ DNI” (people over the age of 23 Do Not Interact”) in their profiles, or the reverse: adult fans with a “minors DNI” sign. In many spaces a taboo on intergenerational interaction has arisen, or at the very least a heavy distaste for it. There’s a general suspicion of older fans: it seems wrong somehow to many young fans that they would be allowed or encouraged to enjoy things in the same way when they’re “all grown up,” and so they look down on those who are doing exactly that. This phenomenon causes further damage to continuity within fandom.

The fact that assorted artifacts from the 01970s seem very much like relics of an ancient time speaks to the relative newness of fandom as a phenomenon capable of leaving things behind. But there are examples that stretch back even further than Star Trek, like an anecdote about a Japanese diary written during the Meiji era full of historical-figure slash fiction. In the replies to that anecdote someone linked what they called an “ancient Chinese fujoshi”: a Qing-era illustration titled “Woman spying on male lovers.”

Like this great-grandmother which lived in the MEIJI period wrote a novel about two historical characters being gay for each other

— shipper ㋐ stan vampire Jesus 🥀🌹✨🐍🍽️🐸🐸🏳️🌈㋐ (@shipperinjapan) June 21, 2019

Japan had fanfic culture 150 years before the rest of the world 😂😂😂

Discoveries of relics like early Star Trek fanart are reminders that fandom has a history extending beyond back past the internet, made by individuals, each with their own passions and obsessions. As Tumblr user polyhexian puts it, “It's like how historians get more excited about finding an ancient shepherds diary than a historical textbook.” Fandom as a feeling can sometimes seem overwhelmingly ephemeral and changeable. Sometimes this can be a good thing, contributing to creativity and spontaneity. But with knowledge and practices increasingly difficult to pass directly from generation to generation amongst constant platform migrations, as well as increased siloing of the older from the younger, a fan can too easily believe themselves to be a product purely of the present, and instead of a step in a chain stretching back centuries and continuing on far into the future.

Preserving fandom’s past for the benefit of the future is a subject receiving increased attention. The zine archive at the University of Iowa is a physical trove of printed matter from the history of 20th-century media fandom. The expansive Fanlore.org, a project of the Organization for Transformative Works, is a massive repository of fandom knowledge, written by and for fans. But a great deal of the links that they catalog are dead; and as people move in and out of different fandoms and the subculture itself, things are erased, left behind, and forgotten.

Not much stays in one place for one long, especially when it comes to digital artifacts. When the Yahoo Groups archive was summarily deleted by parent company Verizon just a few years ago, fandom suffered massive losses, just as it had during the Livejournal purges of the late 02000s, and during the Tumblr porn ban in 02018. Fandom preservation, then, ties into the larger issue of digital preservation as a whole, and specifically the question of how individual and group emotions and experiences — which make up so much of what it means to be a fan — can be effectively documented, annotated, and saved.

There has of late been a surge in people experimenting with printing and binding fanfiction. Members of the fanbinding community, as they’re known, are well aware that the works they’re printing are freely available on the web, and are also technically illegal to sell and buy. Printing out one’s favorite stories and lavishly binding them in leather and gold is not only an expression of fannish affection; it’s also a way of ensuring that they are preserved in stable physical form. Even though the Archive Of Our Own, also run by the OTW, was founded with the express intention of preventing the kind of losses that have struck fan archives in the past, there is still something valuable in expending time and effort to bring fanfiction to life as a book: one that might well be discovered in a thrift store in some unknown future, and posted about for other fans to marvel at. Fanbinding preserves both the work itself and the original fannish passion that sparked the urge to make the bound version in the first place.

Lot of progress this weekend. About 12 volumes in the works. #bookbinding pic.twitter.com/IUte6C5VDy

— ArmoredSuperHeavy - Dead Dove Publishing 💀🕊️🍴 (@ArmoredHeavy) March 4, 2019

There’s no clear solution to the ongoing issue of fandom’s intergenerational issues with memory and continuity, but the spotlighting of discovered relics and the ongoing preservation of artifacts, both digital and physical, is a good starting point. Algorithmic platforms make it all too easy to live totally in the moment, which is as dangerous within fandom as anywhere else.

And as a subset of cultural memory in general, fandom memory is essential if we are to understand how the practices of mass enthusiasm that are now coming to dominate culture as a whole have taken shape. Superhero franchises and pop stars rely on fandom, as do the companies behind them. Surely these giants of culture don’t need any help being remembered, but the ways that fandoms respond to them — whether with love, hate, obsession, transformation — are just as vital to preserve.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe