Many books have been written about the ideas and projects of Stewart Brand. John Markoff’s is the first about the life of Stewart Brand. Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand (02022) provides a definitive look at a quintessentially Californian icon who has spent the better part of six decades at the cutting edge. Best known for founding the Whole Earth Catalog, Brand has had a consequential impact across a congeries of domains, including the American counterculture, modern environmentalism, personal computing, the internet, long-term thinking, multimedia art, publishing, business, architecture, and design.

“Telling the story of Stewart Brand’s life poses a puzzle, for he isn’t someone who can be neatly categorized,” Markoff writes in Whole Earth. “Perhaps it is so difficult to put him in a box because he has such an uncanny knack for seeing the world from outside the box.”

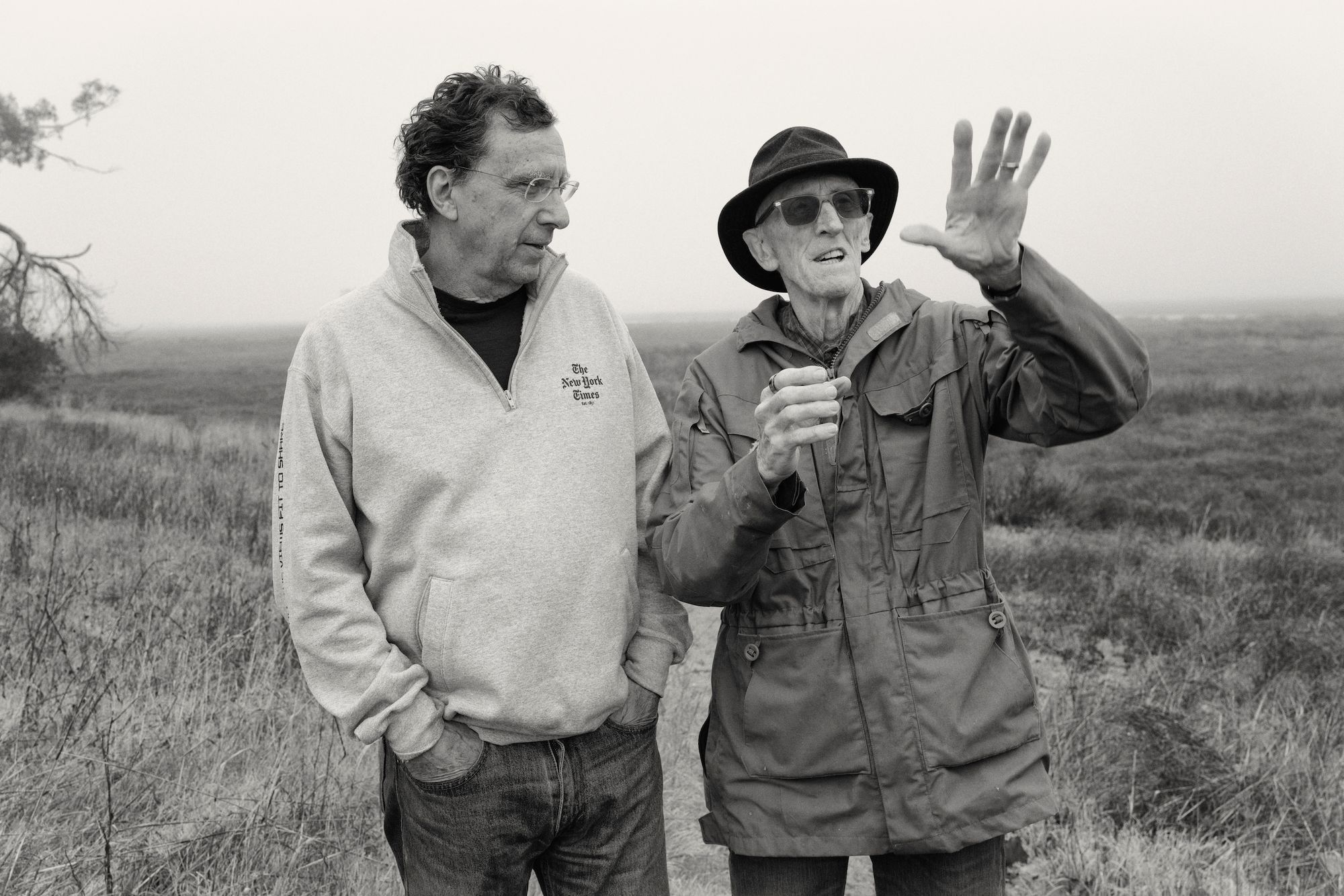

Markoff is uniquely qualified to take on the challenge. A longtime technology reporter for The New York Times, Markoff has covered Silicon Valley since 01977. His book, What the Dormouse Said (02005), explored Brand’s place at the interface of counterculture and personal computing in the 01960s. What’s more, as a Palo Alto native, Markoff has intersected with Brand’s ideas and projects since he was a young leftist activist visiting the Whole Earth Truck Store, where copies of Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog were sold.

Markoff’s book complicates old myths, such as the “rooftop LSD vision” origin story of Brand’s “Why Haven’t We Seen A Photograph of the Whole Earth Yet?” campaign. It also challenges new ones, such as the narratives, increasingly popular in books and articles after the 02016 US Election and the subsequent “techlash,” that the younger Brand’s do-it-yourself philosophy and full-throated embrace of technologies like the personal computer and the Internet were responsible for originating a destructive form of Silicon Valley techno-libertarian ideology.

While Whole Earth is not a critique of Brand, neither is it a hagiography. Brand’s personal and professional failings, as well as his mental health struggles, are relayed in unsparing detail. The result is a vital, nuanced, and necessary portrait of a human being who has always floated upstream of the mainstream.

We spoke with Markoff on the eve of Whole Earth’s publication and its Long Now book launch event. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you first come across Stewart Brand?

I grew up in Palo Alto and I went away for almost a decade for undergraduate and graduate school, but I would be back in the Bay Area all the time. And I was very politically active. That little community around the Whole Earth Truck Store on Santa Cruz off of El Camino was in some ways ground zero for the Mid-Peninsula counterculture, both in a political and a cultural sense. It was in this little cauldron that essentially went from Kepler's bookstore to the People's Computer Company…Ramparts Magazine had been just down the street. The International Foundation for Advanced Study, where they did the LSD research, was around the corner. The Midpeninsula Free University was there. Briarpatch Market. There was a center there and I was not a regular, but I dropped into the Truck Store a couple of times, so I knew the name Stewart Brand.

The first time I saw Stewart was probably either 01982 or 01983. I had been a starving freelancer in the Valley for about five years and I was about to give up. I ended up getting a job at a little startup weekly publication called InfoWorld. It was the first weekly of the personal computer industry when it was going through that shift from the hobbyist world to the industry that it became. I went from living on three thousand dollars a year to having a real job. And so I was at a Comdex computer show, which was a sprawling giant show that had emerged for the personal computer industry.

John Doerr later described the personal computer industry as the largest legal accumulation of wealth in history. And you could see that that was happening at that show. I was at a hotel on the Las Vegas Strip at a party for the Epson printer division, and I was standing in front of the largest bowl of cooked shrimp I’d ever seen in my life. And I looked up and there was Stewart standing on the other side. I recognized him, and I got it instantly: both of us were being sucked into this new industry. Unfortunately for Stewart, it was via the Whole Earth Software Catalog, which was a financial disaster.

I didn’t actually start talking to him for a couple of years. I think the first time I ever spent a lot of time with him was at the first Hacker’s Conference. After that I would call on him when I wanted a source who could take a step back and offer me the big picture. That’s the way I used Stewart in my reporting.

A fair chunk of your book What the Dormouse Said was dedicated to Brand’s place at the intersection of counterculture and personal computing. Why write a biography?

I was getting ready to leave The New York Times in 02016, and I remained interested in the forces that shaped Silicon Valley. Kevin Kelly approached me and said that someone should write Stewart’s biography, and it should be you.

And I thought about it. I said yes because I was interested in the arc of his life. It seemed like there was a narrative there that would be fun to report. It also was a continuity of my interest in understanding what was going on in the Mid-Peninsula. Stewart was a big part of it.

There’s a foundational myth told about Brand’s life concerning how he came up with his ‘Why Haven’t We Seen A Photograph of the Whole Earth Yet?’ campaign: It’s 01966, he’s on the rooftop of his North Beach apartment, high on LSD, and he’s thinking about Buckminster Fuller, looking at the San Francisco skyline, and all of a sudden he’s struck by the epiphany that a photograph of the whole Earth would change everything. Whole Earth complicates that myth somewhat by revealing that the seeds for his vision were planted a few years prior, and that an unpublished 01964 essay on his “America Needs Indians” project already contains a mention of how powerful an image of the earth from space would be.

One of the methodological things about Stewart’s life that I came away with was that ideas he’d be involved in would often bubble, sometimes for decades, before they emerged, and this was an example of that.

He’d stumbled upon the draft text of Lyndon Johnson’s inaugural address while he was hanging out in Washington D.C. in 01964. In it, Johnson describes the view of the earth from a rocketship in space, borrowing language from the cosmologist Carl Sagan. Stewart ran across that text and conflated it with his thinking on Native American culture, and then it got expressed in an LSD fugue state several years later.

It was an example of something I saw over and over again in Stewart’s life.

What’s another one?

There’s a journal of Stewart’s that I call the “Lost Journal,” which wasn’t handed over to the Stanford Archives and that Stewart found in his office during this project. He was keeping this in the summer of 01967. In it, there’s a description of the WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link). He called it “E-I-E-I-O”, short for “Electronic Interconnect Educated Intellect Operation.” He has no memory of it or what he was thinking about. But that was the original vision and it came right out of his intersection with Douglas Engelbart.

Were there any other surprises in this “Lost Journal”?

So Stewart helped set up the Lama Foundation in New Mexico, and he was there for two weeks before he got bored and came back to California. At that point, he wrote: “I’ve decided to come to Menlo Park to let my technology happen here.” He shows up in 01967, right when Silicon Valley is forming. He doesn’t remember why he wrote this. He doesn’t remember it at all. But something attracted Stewart Brand to Silicon Valley at the moment of its formation. That, to me, is just stunning.

The other thing that I learned that reframed things for me was Stewart’s role in Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos (01968). Both Fred Turner [in From Cyberculture to Counterculture (02006)] and I [in What the Dormouse Said] made a big deal of the fact that Stewart ran the camera for the demo — but that was a footnote when I dug into the actual demo. He was a bit player who ran the camera.

What was more important was that the year before, he became an acolyte of the oNLine System (NLS). He was going around giving talks on NLS. He got the basic ideas of the founding technology of Silicon Valley right at the beginning. A lot of the things that Engelbart had to give, Stewart was one of the first people to stumble across.

What potential do you think Brand glimpsed in these technologies that early on? There’s that famous opening in his 01972 Rolling Stone essay on the Stanford engineers playing SPACEWAR! where he writes: “Ready or not, computers are coming to the people. That’s good news, maybe the best since psychedelics.” But we’re talking five years earlier here, before he even published the Whole Earth Catalog.

If you ask Stewart, “Where did the Whole Earth Catalog’s subtitle, ‘Access for Tools,’ come from?” He'll say, “Oh, I was just channeling Buckminster Fuller.” And yes, Fuller's view of the world is: if you want to change the world, give somebody a tool and teach them how to use it. Very simple. But what I can see from that lost journal, is that it wasn't just Fuller, it was Engelbert, too. Engelbart was designing the universal tool. That was the formative idea of Silicon Valley. And that's what's expressed in the Whole Earth Catalog and that's what gets pushed out into the culture much earlier than anybody realized. It was the combination of ideas that were the heart of Silicon Valley that was embodied in the notion of access to tools, and that came out of Brand’s intersection with Engelbart.

Engelbart was actually the first person to really understand the significance of scaling. And he gave this talk in 01961 in Philadelphia at an electronics conference. And Gordon Moore was in the audience. He heard Engelbart talk about scaling, and then, of course, he codified it in 01965 and it became Moore's law. But Engelbart really got it, and I can see Stewart having dinner with Engelbart, and Lois Jennings [Brand’s first wife] remembers this, too. They had a couple of dinners together, and Engelbart would come over and talk about the exponential increase in computing power and its significance, and Stewart had that framing right from the beginning. But even more importantly, he understood that computing was going to be this essential tool for humans earlier than anybody else. And you can see it in the early Whole Earth Catalog, too. The culture and ideology that was emerging from Silicon Valley was embedded in it from the start.

That’s not the way the Catalog is seen. The popular conception of the Catalog links it to the back-to-the-land movement. I came away from the project feeling that that is not the right way to view the Catalog, even though that was the spark.

He did want to share things with his friends who were going back to the land. But the Catalog had its impact on an urban population who were looking for interesting ideas. That was my generation. I can't tell you how many times I'd run into someone and tell them I was working on this project and they'd tell me that they found something in the Catalog that sent their life in an orthogonal direction. Information was scarce back then. It was hard to find interesting things, and Stewart was the curator of lots of interesting stuff that people bumped into.

So the big takeaway for me about the Catalog that I don’t think people realize — and that I realized in the process of doing the project — is that the Catalog emerged from the same forces that created Silicon Valley and digital culture, and it had an impact on the broader culture.

The "Lost Journal" was quite a significant find, then.

It was a surprise to me. It’s a lesson in how, for a biographer, contemporaneous documents are absolutely essential.

Stewart doesn't have a bad memory, but we're dealing with stuff from a half a century before, and oftentimes he would go, “Oh, you know, you should ask so-and-so about this,” and you know, they might be dead. It was challenging. If all I'd had to go on with Stewart's memory, it would have been difficult.

He gave his journals to Stanford in 02000. He was not a consistent journalist. Sometimes there would be great reporting of what happened on a day-to-day basis, sometimes his ideas would show up in the journal and not the context. They were more or less helpful at different points.

Were you able to look through emails to help construct his post-02000 biography?

I was. That’s the good news and the bad news. Imagine being confronted with almost a million emails and trying to find anything.

First of all, a lot of the WELL content was gone. There was no way I was going to get it back. His email corpus, it sort of does go back to 02000, but the cutover from paper to electronic had already started to happen. So the texture is just not there because people weren’t keeping their emails initially, and Stewart didn’t keep his well. So I was struggling with his inboxes; we could never unwind them. Stanford archivists are working on tools that allow you to extract semantic information. We spent months on it trying to just put stuff in order and run them through the Stanford tools. And that was good, but not great. There are other tools that are starting to emerge, like Google’s Pinpoint, but it came out just too late for me. I was just working at the wrong point in history, in between the digital and the paper world.

Beyond What the Dormouse Said, many other books have been written about Brand’s ideas and projects. Where do you situate Whole Earth in the landscape of books on Brand?

There are literally as many as two dozen books that have used Stewart's story to make up one point or another, What the Dormouse Said included. He can sometimes become a kind of cardboard figure that you set down as a set piece. The fact that Stewart featured in the opening of two books that represented the techlash shift in the zeitgeist, Franklin Foer’s World Without Mind (02018) and Jonathan Taplin’s Move Fast and Break Things (02017), startled me. The idea that Stewart was the original sin of Silicon Valley is just crazy. Calling Stewart the “first digital utopian”? I’m not even sure if I’m comfortable with the term “utopian” for Stewart. He would call himself a pragmatist. Digital optimist, I think, is a better word than utopian.

I made an effort in Whole Earth to try and put myself aside. I wanted this to be Stewart’s story and not get in the way of it too much, for better or ill. And you can see that I failed in places. There were moments where I had to try and interpret things. But on the whole, my goal was to just tell the story.

What do you think about the critiques Foer and Taplin put forth in their books?

I think that Taplin got it more right than Foer in saying that there were the original digital utopians, and then at the beginning of the dot com era there was the PayPal mafia, and that’s when the real break in the culture of Silicon Valley occurred.

My sense is the original archetype of the Valley originally was best expressed by the partnership of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. You had one guy who was a hacker who just wanted to share the technology with his friends, and you had another guy who understood there was a market there for the product. And that was the best and brightest of Silicon Valley for a long time. And then the Valley culture shifted to being all about the money. And that’s disappointing to me.

You make a point in Whole Earth of challenging some of the connections Fred Turner, author of From Counterculture to Cyberculture, draws between the libertarian, do-it-yourself philosophy espoused by the Whole Earth Catalog and the emergence of libertarian digital culture in the 01980s and 01990s. Could you unpack that a little bit?

Fred and I have never had this conversation, but where I have difficulty with Fred is what he hangs on to the WELL, because I was there. I was a part of the WELL community right from the beginning. And I do believe that Turner is accurate, that at that period in the second half of the 01980s, a libertarian digital culture was emerging in America, but to say that the WELL was any kind of fount of that is just a mistake. There were a variety of sites for the emergence of networking culture. I think the kind of culture Fred identifies came out of Usenet, which was the hacker culture distributed in the Unix centers around the country, and which emerged during that same period.

The WELL never had a population of more than fourteen thousand. I think the reason it got an out of scale reputation was Stewart’s brilliant marketing move in giving people like me and Steven Levy and other technology writers free accounts.

So that’s where I struggle with Fred’s thesis. The thing that’s hard about Stewart’s politics is that he clearly did start out as a libertarian. He had a brief infatuation with Ayn Rand in college. But then the arc of his life was really transformed by the year he spent in Jerry Brown’s administration in the late 01970s. He clearly came away feeling there was a role for good government. That’s not a libertarian sensibility. And then, if you go as far forward as [Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto (02009)], it’s not written there out front, but you can find it in there: who’s going to enforce the kinds of things that we need to do to combat climate change? Strong government.

So I don’t think it tracks with Stewart’s actual views. Stewart’s very open to stuff, and he won’t criticize stuff. The classic example, and one not found in Fred’s book, is that he walked away from the WELL feeling it was a failure. He left. He quit the board. He ran into some of the behavior that we see in the modern social media world, and he was aghast. He felt that the WELL had failed as a social institution. He didn’t criticize it publicly because he likes to be optimistic about technologies and their impact.

Personally, I’m a “glass half full” guy; I’m sort of somewhere in between. I have this notion that humans make a difference in how we apply technologies, and you could take the same technology and use it for one thing or another. It’s a human decision. Stewart tends to be an “access to tools” kind of guy at the end of the day: Technology has gotten us into this, and technology is going to get us out. That’s his worldview, and he sticks to it.

One of the fascinating moments in the book, which you’ve just alluded to, sees Brand on the receiving end of virtual community vitriol in the WELL in the early 01990s — the kind of ostracism dynamics that are today framed by the polarizing term “cancel culture.” As someone too young to be on the WELL in its glory days, I’d admittedly always assumed it was more of a utopian scene than you make it out to be. The example highlights how this has been a part of online discourse from the start.

If you want to go back into the history of that kind of behavior, and of virtual communities not being the kind of utopian communities that we would like them to be, you should read True Names (01981) by Vernor Vinge, the computer scientist and mathematician who originated the notion of the singularity. It’s a novella in the cyberpunk science fiction genre.

Vinge was teaching at San Diego State University in the 01970s, and he saw the way his students behaved on the bulletin board systems. And he said to himself: Hmm. What happens if you take bulletin board culture and you add infinite bandwidth and infinite processing power? What kind of world do you get? And what you get is a world in which you need to protect your true name at all costs. It was a really early warning about the reality of virtual worlds.

Four or five years before Stewart left the WELL, he was interviewed by one of the San Francisco magazines. There was a question in there about behavior, and he basically asserted that when you lived online, you acted like an angel. Not so much, but it was early then.

I believed that too. I’m very sympathetic to that view because I grew up with ARPANET and the internet, and I really believed in John Perry Barlow’s vision of the world for a while. And then I realized that the cyberpunk writers were right. The internet was simply a reflection of society in so many ways, with all the good and all the bad.

Did you discover anything surprising about the origins of The Long Now Foundation in your research?

I was aware of the arc of the Foundation early on, because I was a big fan of [Long Now Co-Founder] Danny Hillis and did some reporting on high performance computing. I learned about Long Now probably sometime in 01994. Danny took me on a walk and explained his vision of the 10,000 Year Clock and talked about the importance of long-term thinking. I thought it was interesting, and I thought the Clock was worth doing in itself. One of my great regrets is that I didn’t write about it.

What I learned about that I didn’t know in terms of the early history of Long Now is that Danny sent a letter out to a whole bunch of people he knew and everybody thought the project was completely nuts — except for Stewart.

Why do you think that was?

There is a Silicon Valley view, the ‘Don’t Look Back’ view of the world that I’d run into for a long time. Steve Jobs was archetypical of it. ‘Why bother to look back at the past? Let’s invent the future.’ Many people in Silicon Valley just didn’t get it.

I was moved by Whole Earth’s frank discussion of Brand’s mental health struggles at various stages of his life. There seemed to be a pattern where he would fall into a depression that functioned as a kind of springboard that launched him into his next creative project. Were you surprised by how forthcoming he was when you were interviewing him for the book?

I wasn’t surprised, but I was appreciative. It's difficult for me to push into people's interior lives; I've never been that kind of person. But Stewart was really an open book. In a sense, he was using our conversations to think about his life. I was there once a week, for half a day, for a year and a half. The subject of our conversation would usually be based off of what I’d picked out of his archives at Stanford, which were voluminous. There was nothing that was a secret. He was very open about his failures and proud of his successes. But he acknowledged that there were a lot of failures. It really was a Sometimes a Great Notion kind of thing. There were lots of notions. And every once in a while, one would be spectacular.

Yes, I found it both humanizing and insightful to see the failures between the successes, and how he channeled what seemed like a constant boredom into creative projects in so many different domains. Or perhaps “restlessness” is a better word.

Yeah, that’s a good way to put it. He would get restless and move on, and that was his genius. I have a friend who's a journalist whose tagline at the bottom of his email is from Camus: “Persistence is the method.” Stewart would persist for a while, and then he'd move on to something else. That's also a method that turns out to be very effective.

The real continuity in Stewart’s life is that he’s still doing what he promised to do when he took the conservationist pledge when he was eight or nine years old. [The original Outdoor Life Conservation Pledge reads: “I give my pledge as an American to save and faithfully to defend from waste the natural resources of my country — its air, soil, and minerals, its forests, waters, and wildlife.”]

When the obituaries are eventually written about Brand’s life, it’s safe to assume that the first line will mention the Whole Earth Catalog. How do you think his legacy will be assessed by future historians, say, a century from now, or 500 years from now?

I was faced with the challenge of figuring out when to end Stewart's story because he's still active, and he’s still doing interesting things. And I made a decision that I couldn't assess either Long Now — because you won't be able to assess the impact of Long Now for at least a couple of centuries — or Revive & Restore. So I decided to use Revive & Restore as a branch point, and I ended the book with its creation.

That was arbitrary, but it speaks to your point: how do you assess Stewart's impact? And I actually hope that Stewart is remembered for the idea of the value of a planetary consciousness. He doesn’t push that idea hard, but he’s associated with it very closely. To me, it’s why Brand is still relevant, and why we might be interested in looking at his life right now. The idea of a planetary consciousness is a counterweight to the rise of nationalism. I hope that idea is the one that carries forward.