Lightning, Stars and Space: Art That Leaves the Gallery Behind

In Part I of our exploration of Land Art in the American West, we covered the birth of the Land Art movement in the 01960s and some of the seminal works created by Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt and James Turrell, which expanded the definition of art and opened up new possibilities for the location of artworks. Drawn to the desert for its long vistas, compelling terrain, beautiful light and dark night skies, these artists pushed through the boundaries of art in their day to create monumental works that explored the expansiveness of earth and time. Though the early death of Smithson dampened the momentum of the movement, the ideas around Land Art had taken hold.

In Part II of our series, we move out of the 01960s to explore the work of three artists who created their major works during the 01970s and 01980s. We see a shift with these artists to a focus on complete control over the exhibition of their work and meticulously curating the experience the viewer has coupled with a goal of permanence of the artwork in situ. Marfa, Texas is only about 80 miles from our Clock Site, making Donald Judd’s work there especially relevant to us.

Donald Judd and Marfa, Texas

Donald Judd began his artistic career as a painter in New York in the late forties. He graduated from Columbia University with a degree in philosophy in 01953 and was soon making almost exclusively three-dimensional artwork. Like many other artists in the 01950s and 60s, he rejected traditional painting and sculpture — as well as the museum gallery system of exhibiting art — as too limited.

This reaction against the conventional art world manifested itself in different ways for different artists. Early large-scale Land Art such as Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jettyand Michael Heizer’s Double Negative was created in direct opposition to the idea that art was an object which could be exhibited in a room in a museum, or even purchased and mounted on a wall.

Land Artists literally fled New York City for the desert, where few art collectors ventured, and, in Heizer’s case, made negative artwork — excavations in the earth which could not be commercialized. Similarly, the subject of Judd’s artwork came to include “the relationship of the object to space and the larger environment.”¹ But as Judd’s work matured he strove to create art that was in the American Southwest, not simply outside New York City museums.

Judd had the opportunity to develop and articulate his own artistic perspectives by writing art criticism for major art journals in the early sixties. His 01964 essay Specific Objects defined an emerging approach to art. “The work is diverse,” he wrote, “and much in it that is not in painting and sculpture is also diverse. But there are some things that occur nearly in common.”

One main characteristic that Judd identified is three-dimensionality. He argued that this art “resembles sculpture more than it does painting, but it is nearer to painting.” Judd wanted to avoid both the composed nature of traditional sculpture (“Most sculpture is made part by part, by addition, composed. The main parts remain fairly discrete.”) and the illusionary nature of traditional painting (“Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface.”).

“Judd’s art produces local order, meaning that there is no framework surrounding creative experience.” — Art historian David Raskin²

Judd’s concern for the relationship between an art piece and the space surrounding it led him to develop very particular standards for how art should be displayed. He was extremely critical of the way most galleries curated their exhibits and made it one of his highest priorities to control the circumstances in which viewers experienced his art. Former Tate director Nicholas Serota writes that

his attention to the installation and presentation of his own work, and that of artists whom he admired, established new parameters for the display of art, challenging and eventually changing the conventions of museums.³

Judd wanted exhibits that were not only carefully installed, but also permanent. He observed that artists’ work could be distorted not only by improper display but by the passage of time. In later years, when he established The Chinati Foundation to permanently maintain the artwork at Marfa, Texas, he made his intentions clear:

Somewhere a portion of contemporary art has to exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be. Somewhere, just as the platinum-iridium meter guarantees the tape measure, a strict measure must exist for the art of this time and place.⁴

Judd’s first opportunity to design his own exhibition space came in 01968 when he purchased a former garment factory in SoHo at 101 Spring Street.

Judd cleared the cast-iron-frame building out to create open and brightly sunlit floors — each one designated for either living, working or exhibiting art. Soon after, though, his aspirations outgrew the dense urban setting of New York City and he began searching the southwestern U.S. for a site where he could permanently house comprehensive collections of his own and other artists’ work. This search led him to Marfa, a small town in western Texas where he was to spend much of his life converting old industrial buildings into meticulously designed living, working and exhibition spaces.

Donald Judd first encountered the landscape of western Texas in 01946 while en route to Los Angeles and sent a telegram from Van Horn — about 75 miles from Marfa — to his mother:

“dear mom van horn texas. 1260 population. nice town beautiful country mountains love don.”⁵

Judd began renting a house in Marfa in 01973 and purchased two former army buildings which he began to renovate, though he did not make Marfa his permanent residence until 01977. With the help of the Dia Foundation, whose mission “to commission, support, and present site-specific long-term installations and single-artists exhibitions to the public” conforms remarkably well to Judd’s philosophy, Judd began purchasing more land and buildings. He also started working on the art pieces for Marfa, and in 01980 fifteen concrete sculptures were among the first pieces to be completed.

Another seminal work by Judd, 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, reveals his deep commitment to both the works of art and the context in which they are exhibited. The 100 works were created over a number of years and installed in two large former artillery sheds. Extensive reworkings of these two buildings opened the interior space up to a flood of natural light through the replacement of the garage doors with walls of glass. Vaulted roofs were added to heighten and refine the proportions of the buildings; these proportions were echoed in the installation of the 100 works. The works themselves, 100 aluminum boxes with identical outside dimensions, but with different interior treatments, offer a subtle and continuously shifting experience of the artwork as the angle of the light outside changes and plays off the metal exteriors and varied interiors. The viewer is rewarded with patience and the piece reveals itself over time.

In 01986, Judd formed The Chinati Foundation to ensure that the site would continue to develop and to be maintained, and the following year he held an open house in Marfa with the town’s residents, understanding that a permanent installation there would be an important part of the community. The complex now includes 15 buildings — mostly old military facilities — as well as ranch land, and permanently displays bodies of work installed not only by Donald Judd, but by Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Richard Long, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, John Chamberlain, and several others.

Judd’s careful execution of his vision for Marfa allowed him and the artists he invited there to create artwork on their own terms. An artist’s control over their work often diminishes or disappears once it leaves their studio, entering the world of art collectors or museums where it can continue to change hands indefinitely. Marfa offered the opportunity for Judd to be both artist and curator, and it assured that his installations would remain unaltered as long as the institutions that maintain them survive. For Judd, these conditions were paramount.

Judd’s own buildings and those of the Chinati Foundation manifest his ideals: his demands on art and on the manner of its installation; its connection to life as it is lived, to architecture, and to the landscape.⁶

Donald Judd passed away in 01994, having established The Chinati Foundation as a caretaker for Marfa as well as The Judd Foundation to maintain and preserve his own work there and in New York.

My first and last interest is in my relation to the natural world, all of it, all the way out. This interest includes my existence […] the existence of everything and the space and time that is created by the existing things. Art emulates this creation or definition by also creating, on a small scale, space and time. — Donald Judd

Charles Ross and Star Axis

Like James Turrell, Charles Ross came to the art world with a scientific background. He attended UC Berkeley, graduating with a BA in mathematics before completing his MA in sculpture in 1962. His early work was mainly focused on installations using welded steel, plexiglass, prisms and lenses, sometimes in collaboration with theater and dance groups.

Amongst the materials Ross worked with early in his career, prisms played an especially important role. In 01965 he developed a new technique for building large, clear prisms and began exploring the possibilities of prisms as sculptures. He’d been spending his time working and exhibiting in both San Francisco and New York and came to know Michael Heizer and the other artists in the Dwan orbit. Ross’s transition from multi-media installationist to prism expert prompted Heizer to write an obituary for Ross, marking the death of his early work period.

Ross exhibited his new prisms at the Dwan Gallery in New York three times between 01968 and 01971. Over those years, Ross’s inculcation into the scene that gave birth to Land Art seems to have turned his thinking about prisms inside-out:

In 1969 Ross shifted the emphasis of his artwork from that of the minimal prism object, to the prism as an instrument through which light revealed itself so that the orchestration of spectrum light became the artwork. This began his life long interest in projecting large bands of solar spectrum into living spaces. — Charles Ross Studio

Rather than objects on pedestals for people to gather around and look into, prisms for Ross became a tool to create an artwork that instead surrounds its viewer.

In his progression from creating sculptural objects to immersive gallery installations, Ross sought communion with light. The next step in that direction took him, along with the Land Artists he’d met working at the Dwan Gallery, beyond what New York could offer and into the American Southwest. In 1971 he conceived Star Axis, his signature Land Art piece.

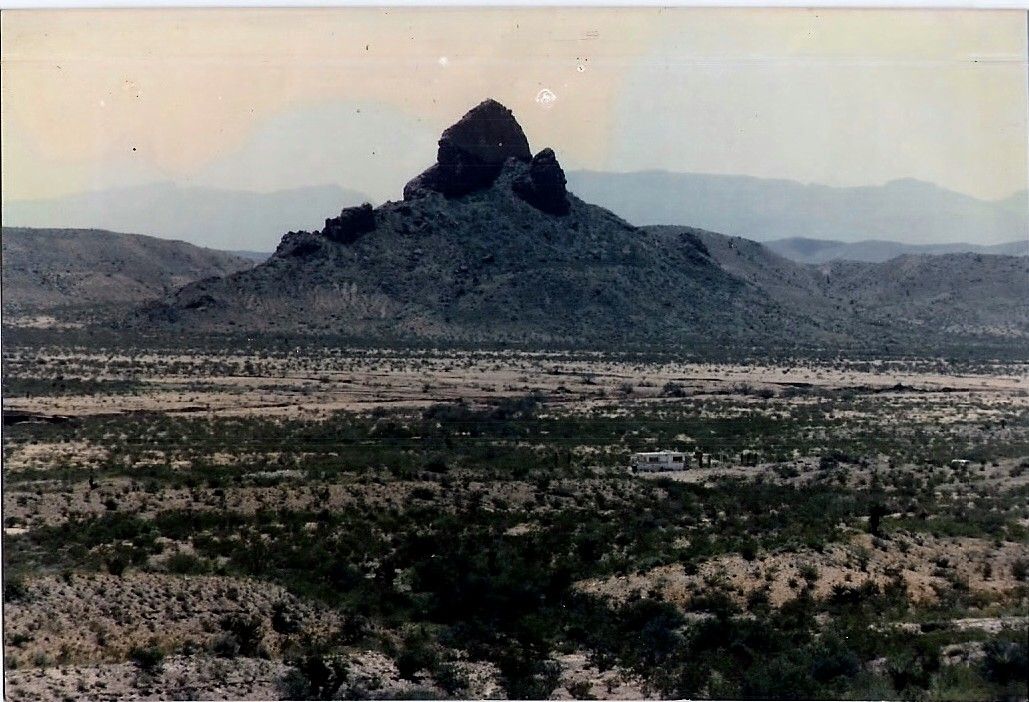

After four years of searching for a suitable location, Ross began construction on what he calls an “architechtonic sculpture,” a sculptural representation of stellar alignments and the ways they change over long time periods. The piece is meant to evoke the deep history of humanity’s relationship to the stars. Built on a mesa in the New Mexico desert, Star Axis has been under construction for decades and will be eleven stories tall when complete. As a naked-eye observatory, Star Axis features alignments with the Sun on solstices and equinoxes, as well as a long stairway and tunnel that are aligned with the Earth’s axis, allowing the axial precession cycle currently centered on Polaris to be viewed while climbing the structure.

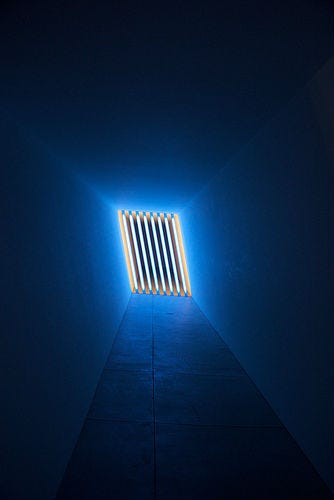

Star Axis features, among other things, an opening at the top of the Star Tunnel that is aligned with Earth’s Axis so that it points directly at the celestial pole — the point in space around which we observe the stars rotating over the course of a night. For most of human history, Polaris has been very close to this point and so has been known as the North Star or the Pole Star — it appears to remain motionless while all the other stars spin around it. The Earth’s axis wobbles, though, every 26,000 years and this axial precessioncauses Polaris to appear to move away from the celestial pole. As Polaris shifts farther from the celestial pole, it begins to rotate through the sky in a wider circle.

Standing at the base of Star Axis’s Star Tunnel, a viewer sees only a tiny portion of the sky surrounding the celestial pole. This signifies Polaris’s extreme position within the precessional cycle at its closest to being our true North Star. While ascending the tunnel, a visitor’s perspective shifts so that more sky is revealed, which signifies Polaris’s shift away from the celestial pole and towards a wider circular motion in the sky. The peak of the tunnel is the opposite extreme — Polaris’s orbit when it is farthest from being our North Star.

Ross hopes to incorporate these astronomical details along with alignments with solstices, equinoxes, the equator and more into an experience combining site and structure that communicates our multi-millennial relationship with the stars.

It’s about the feeling you get when you’re grasping your relationship to the stars. Ultimately, it’s about the earth’s environment — both in time and space — extending out to the stars. — Charles Ross

Turrell, Ross and others create experiences that can only be had in particular places, often at particular times. These experiences are meant to create for the viewer a relationship with the surrounding environment and to expand, temporally and spatially, what constitutes that environment. A small contingent of Long Now Staff and Board members was able to visit the site in 02000 and found the scale and multi-decade effort impressive. Stewart Brandpointed out after the visit:

Astronomical alignments can be pretty exciting, and they are intensely educational. We don’t usually sense the grand orientations, but when we do we take on something deep.

The Precession of the Equinoxes and its 26,000 year time frame can be apprehended personally and thrillingly. — Stewart Brand

Walter De Maria and The Lightning Field

Walter De Maria’s most well-known piece, called The Lightning Field, is a great example of Land Art’s interest in crafting experiences. It is physically made up of 400 stainless steel poles set out in a grid in western New Mexico. Nearby, there is a cabin for visitors to spend the night in hopes of catching a glimpse of thunderstorms. The experience designed by De Maria is a specific one and includes strict instructions for visitors (no vehicles, cameras, or outside food) that are enforced by the caretakers of the piece, the Dia Art Foundation.

Created in 01977, The Lightning Field is an experience of the land and the sky and the ways they interact, but it also explores our attempts to quantify our environment. Measurement is a theme throughout much of De Maria’s work and it is embodied in the dimensions of The Lightning Field. The grid of poles measures one mile along one side and one kilometer on the other, mixing normally incompatible systems and illustrating their arbitrariness. Along similar lines, De Maria’s Silver Metersand Gold Meters feature plugs of precious metals inserted into plates of steel. The total precious metal contained in each plate is one troy ounce, but it is distributed over an increasing number of plugs (the squares of the integers 2–9) for each successive plate.

…in its exploration of the numerical in relation to the serial, De Maria’s trajectory has been singular. It ranges from the vast scale of The Lightning Field — a Land Art work in New Mexico realized under the auspices of Dia Art Foundation in 1977 — whose grid of four hundred stainless steel poles spans a field a kilometer by a mile in dimension, to this more modest pair of works, which similarly incorporates both metric and English (or Imperial) systems of linear measurement. Common to both, too, is the use of highly polished metal components and pristine workmanship, together serving to impart to the piece a sense of absoluteness — of indubitability — as if it existed outside the vicissitudes of chance and the inchoate. — Dia Art Foundation

During a visit to The Lightning Field in 02000, a small group of Long Now Staff and Board Members found the experience, given the actual extreme rarity of lightning, more focused on the surrounding landscape:

There was no sign of lightning but we had an incredible sunset and the cabin is actually the best part. At the least this is probably the coolest place to stay in New Mexico. The Lightning Field itself is great at sunset/rise and almost unseen otherwise. Each 22ft tall by 2 inch diameter solid stainless pole is parabolically tapered at the top to a sharp point. The stainless has remained shiny for 23 years. An interesting effect occurs as the sun angles down toward the horizon and picks up reflection off the taper, they almost look as though they have lights at the tops.

Since lightning can never be guaranteed, the experience of visiting the piece is often more about meditation and exploration than it is about watching a particular phenomenon. The possibility and implication of lightning hints at the power of the environment, while the grid and its measurements allude to our hopes to quantify and bring order to it. Through simple, minimal creations, Land Art or otherwise, De Maria creates experiences that evoke the world’s complexity and defiance in the face of our attempts to understand it.

Land Art started in many ways as a rejection. The early participants all consciously sought to escape the limits and the commodification of the modern, minimalist gallery scene and so defined much of their work in the negative (Heizer’s Double Negative making it explicit). As the scene grew and pulled in more artists, the ideas being realized through Earthworks began to take on a positivity. Donald Judd wanted full control over the environments in which his sculptures were viewed and he wanted them to remain where he put them permanently. Charles Ross’s explorations of the sun and stars led him away from the bright city lights to a place where the sky is a defining characteristic of the landscape. Walter De Maria envisioned an experience that could only be sufficiently crafted and controlled in an isolated natural setting.

Fully immersive, designed experiences, in touch with the natural environment and evocative of our relationship to it, often installed with the intention of permanence (or at least of letting nature decide how and when to end the show instead of a curator) came to be the hallmarks of the genre. These characteristics describe some of the 10,000 Year Clock’s aspirations as well; the paths and tools forged in the Land Art movement’s workshops and sketchbooks are a resource for Long Now’s attempts to provide an experience that encourages long-term thinking through The Clock. In a third installment, we’ll take a look at more contemporary efforts within Land Art — some of the original artists are still working away while many newcomers have helped to keep the movement vital.

Written by Austin Brown, Danielle Engelman, and Alex Mensing. Edited and updated by Ahmed Kabil.

Learn More

- NPR’s Weekend Edition profiled Donald Judd and his Marfa artworks in 02009.

- Ross Andersen visited Charles Ross’s Star Axis in 02013 and recounted his experience in Aeon.

Works Cited

[1] Chinati: The Vision of Donald Judd, Marianne Stockebrand p. 272)

[3] Stockebrand, Marianne. Catalogue. In Donald Judd, edited by Nicholas Serota. Distributed Art Publishers, Inc., New York: 02004, pp. 272.

[4] Ibid., 280.

[6] Stockebrand, pp. 12.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe