This is the third article in our series, Music, Time and Long-term Thinking. Two previous articles explored long-term thinking in several musical domains, with focus on three artists: Brian Eno, John Cage and Jem Finer. For this third entry, we open our field of interest to broadly survey projects with unique temporal approaches.

One of the easiest ways to explore temporality through music is to simply slow it down. Just as we would seem incredibly slow to a hummingbird, slowed-down recordings can make us feel like the world is slowing down, each moment resonating with new intensity.

Along these lines, Norwegian composer Leif Inge has taken Beethoven’s 9th symphony and stretched it to 24 hours in length while maintaining the original pitch. In 02004, the piece was presented as a “once-in-a-lifetime all-night pajamas-please sleep-over concert-event” at San Francisco’s 964 Natoma, organized by Member Aaron Ximm. As Ximm describes it:

The result is a remarkable remaking of Beethoven as massive soundscape: a piece in which familiar motifs develop twenty times more slowly than we’re used to, at times lovely, at times overwhelming. It is the best-known symphony in the world transformed: transformed into a dramatic and haunting and hypnotizing soundscape that passes like clouds over a vast landscape.

A meme from 02010 captures this same effect with a pop song. A user on Reddit posted a link to a recording he’d created of Justin Bieber’s “U Smile” slowed down 800%. The result was shared virally across the internet for the next several days.

The original Soundcloud post of the recording by Shamantis has been deleted, but remnants still exist on YouTube.

A Soundcloud user by the name of PsychicWhoosh captures the unnerving beauty of this piece in a comment on the track:

This thing is having a profound impact on my view of the universe at the moment, that here, hidden in this crappy, commercial pop song is a piece of music so transcendent in its cosmic beauty, it is moving me to heights of spiritual ecstasy. It was there all along, like a cipher hiding in plain sight which no one knew needed decoding. It simply needed to be tuned to the right frequency, to be tracked along the proper coordinates of time.

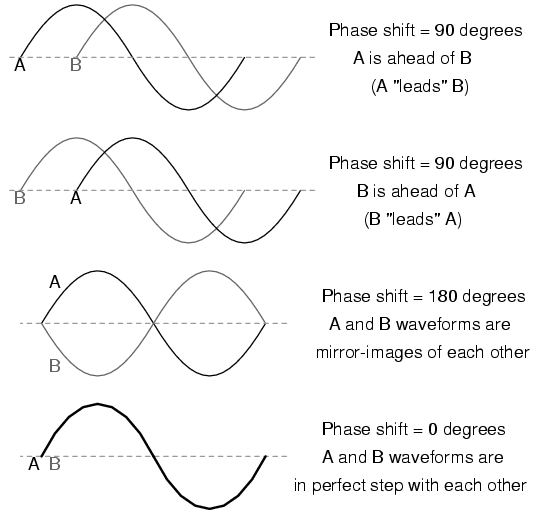

In contrast to dramatically slowing a recording down and extending its length, artists have also explored the possibilities of repeating short recordings over and over. The history of looping in modern composing is a story of the accidental beauty of technological imperfection and decay. In 01965, composer Steve Reich recorded a preacher in Union Square, declaring “It’s gonna rain.” While attempting to start a second loop halfway through the first recording, Reich found that the technology was imperfect, creating what is known as a phase shift.

The idea behind a phase shift is that two identical loops start off in sync, and then over time one drifts, creating a doubling effect. As the second loop shifts further, the loops conflict more and more, until their waveforms are exactly opposite. From this point the second loop continues its shift and eventually catches back up with the first loop, bringing the loops back into sync and completing the process.

Steve Reich’s “It’s Gonna Rain.”

While originally unintentional, Reich liked the sound of the phase shift, and the piece “It’s Gonna Rain” became Reich’s landmark composition and a significant contribution to minimalism and process music. Brian Eno, in a Long Now lecture, cited “It’s Gonna Rain” as his first experience with minimalism and the genre that would come to be known as ambient music.

Just a few years after Reich’s creative accident, a young composer named Alvin Lucier was also experimenting with looping. The premise was simple — Lucier recorded himself reading a paragraph of text while sitting in a room:

I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.

Alvin Lucier — I Am Sitting in a Room

The piece thus unfolds exactly as Lucier explains it, with the recording slowly sliding from intelligible language into the haunting natural reverberant tones of the specific room. Here the room has become the instrument as the recording loop deviates further and further from the original recording.

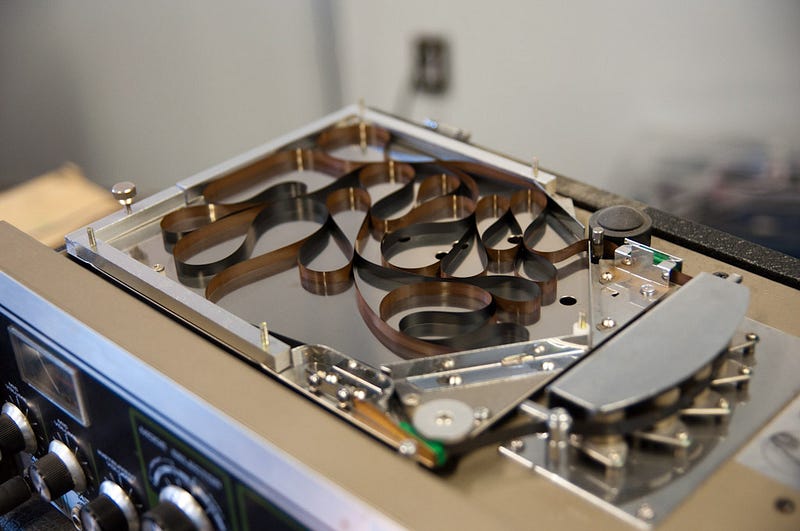

Another major piece of music that incorporates looping is William Basinski’s “The Disintegration Loops.” Former Pitchfork Editor-in-Chief Mark Richardson tells the story of Basinski’s process in his article about the collection:

In the 1980s, he constructed a series of tape loops consisting of processed snatches of music captured from an easy listening station. When going through his archives in 2001, he decided to digitize the decades-old loops to preserve them. He started a loop on his digital recorder and left it running, and when he returned a short while later, he noticed that the tape was gradually crumbling as it played. The fine coating of magnetized metal was slivering off, and the music was decaying slightly with each pass through the spindle. Astonished, Basinski repeated the process with other loops and obtained similar results.

The very process of media decay, a running theme on our blog, led to a beautiful piece that turns the decay into a meditation on the impermanence of sound and structure. Basinski was listening to the loops on September 11th, 02001, when the World Trade Center fell. Basinski decided to record a video of the billowing smoke of the collapsed towers from his roof in Brooklyn, and set one of the loops to the video, adding a haunting, poignant twist to the theme of decay.

The Disintegration Loops is one of the most powerful manifestations of the inevitable cycle of life ever committed to tape, even as it documents the inevitable decay of all that is committed to tape. The very passage of time is its most effective instrument. — MMLXII

Like any good musical genre, ambient music started as a description of something new and unique, quickly garnered a following and imitators, was codified and sub-divided, and ultimately spun off communities of creators, promoters and aficionados.

Beyond just coining the term, Brian Eno set forth many new paths through his foundational work. One direction ambient explorers inspired by Eno took was into textural explorations: music that was produced largely to aurally represent something — a place, a vision, a feeling — almost exclusively through its timbre. Harmony and rhythm aren’t unimportant to this music, but they tend to work in a subtle, supporting role to combinations of droning synthesized and recorded sounds.

A record label based in Rome called Glacial Movements produces a blend of this style that it calls “glacial and isolationist ambient.” The music is meant to evoke the vastness, the stillness and the cold of the Arctic.

The density of the Arctic’s frigid air makes sound travel quickly and crisply to one’s ears. But, because it can be such a still, isolated place, those sounds tend to be deep and structural — like ice floes slowly grinding against one another — or as diaphanous as ice crystals and snowflakes forming out of the air itself.

Just as John Cage’s experience in a supposedly silent anechoic chamber revealed to him the deep and low frequencies produced by his body itself, the seeming silence of the Arctic can heighten one’s sonic awareness. The music features sounds as hard and smooth as miles of perfectly clear, ancient ice, or as light and crunchy as footsteps in fresh snow.

The Arctic is also known for its extended light and dark cycles, alternating between months of day and months of night. Likewise, the music of Glacial Movements tends toward a kind of stasis, without clear rhythmic markings to count time as it goes by.

Similarly inspired by the polar region’s unique sound profile, Paul H. Miller, aka DJ Spooky, has created music that takes a very different approach to representing cold, icy realms. His particular interest in Antarctica stems less from its aesthetics than from the singular political situation it inhabits — Antarctica is without national affiliation — and the ecological implications of such an arrangement.

Miller has written a book in conjunction with scientists Brian Greene and Ross A. Virginia called The Book of Ice. Accompanying the book is an album-length composition featuring sounds recorded in Antarctica called Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica.

DJ Spooky discusses John Cage’s influence on his project Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica.

The glacial landscape portrayed therein is comparatively livelier than that of the Glacial Movements recordings. It starts off with a raucous reminder of the animal life that calls the Antarctic home before transitioning into a more traditionally ambient portrayal of the region’s significant winds, followed by a strings portion perhaps meant to evoke the continent’s missing Anthem that gives way to parade-like drums (celebrating independence?). And that’s just the first 15 minutes.

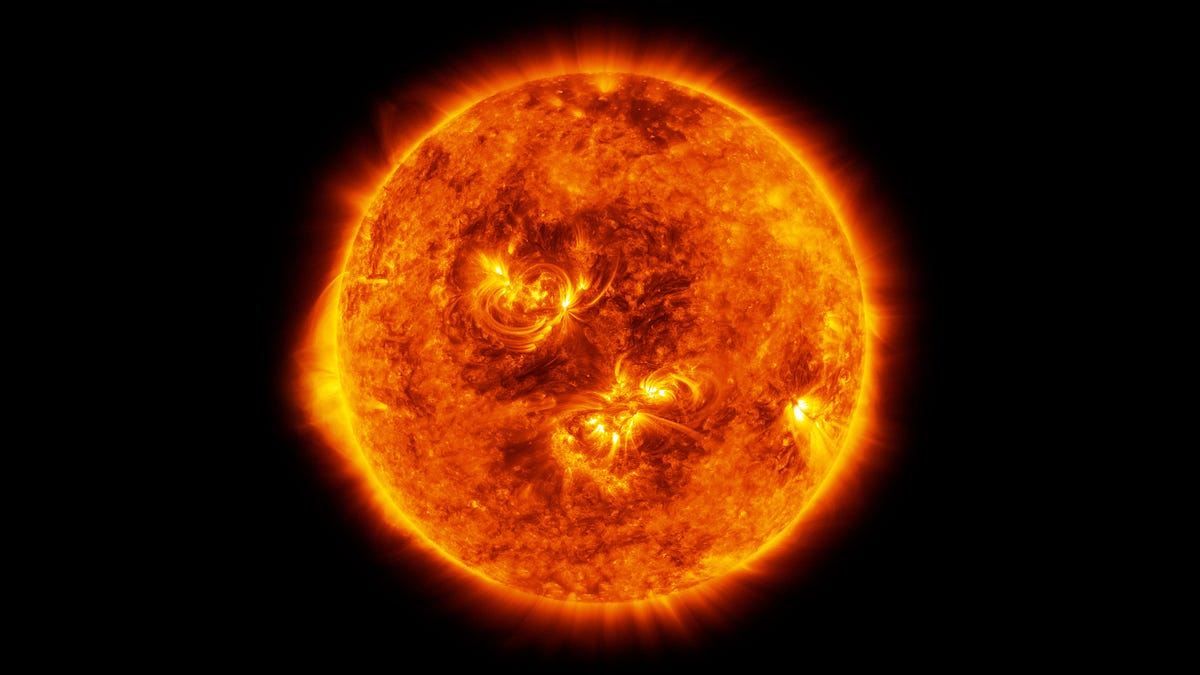

Exploring realms even farther afield, Robert Alexander’s work leaves our planet altogether. In partnership with the Solar and Heliospheric Research Group at the University of Michigan, Alexander uses astronomical data on the sun and the solar wind to generate sound and music. One piece he shared with NPR in 02013 is generated from 40 years’ worth of measurements tracking the sun’s rotation. It features a deep rumble topped with blips of static. The piece is a fairly straightforward example of what he calls sonification—aurally representing a dataset. In some of his other work, he incorporates sonified data into compositions of his own.

Alexander spoke to Vice Media in January of 02013 about the way he crafts his compositions from scientific research. He also explained that his musical approach to exploring the data led to a unique analytical discovery. He noticed an acoustical resonance between two data sources and was able to identify a correlation between carbon and the solar wind that scientists later confirmed in a published paper.

Fortunately, one doesn’t need access to a space program to sonify astronomical data. A community of enthusiasts has coalesced around the recording of Very Low Frequency radio waves. VLF waves can be 10 to 100 kilometers in length, making them useful for certain types of communication, but also susceptible to a great deal of atmospheric interference.

It’s the latter characteristic that makes them interesting to a certain class of audio-hobbyist. Interference that can be heard in the recordings of VLF waves is generated by many sources, but is usually dominated by the sound of the AC power grid.

Tuning in from a remote area more than a few miles from power lines, however, will yield primarily natural sounds — lightning strikes, primarily, but also the Aurora Borealis and Australis, ethereal phenomena caused by interactions between the solar wind and our planet’s magnetic field. Stephen P. McGreevy has made an album of just such recordings. He traveled to remote locations all over North America to gather these eery, glitchy sounding passages.

Stephen P. McGreevy discusses his process of capturing sounds of Earth’s magnetic field.

Whether exploring temporality through slowing or looping music, trying to take people to an imaginary frozen tundra, depict the actual hellscape of the sun, or record interactions between the two, artists are finding music to have sufficiently pliable boundaries to accomplish their expressive tasks. These projects have vastly different aims and influences, but seem in some way to evoke vastness and awe, themes that overlap with the Long View.