Speed is a Choice

The authors of Abundance talk with Michael Pollan about the pace of governance, the environmental questions of our age, and the federal policies that drive scientific progress.

The Pace of Governance

Michael Pollan: Congratulations on the book. It is very rare that a book can ignite a national conversation and you’ve done that. I was watching CNN on Monday morning and they did a whole segment on “abundance” — the concept, not your book. They barely mentioned you, but they talked about it as this meme. It has been mainstreamed and at this point it’s floated free of your bylines and it has its own existence in the political ether. That’s quite an achievement, and it comes at a very propitious time. The Democratic Party is flailing, in the market for new ideas and along comes Abundance. The book was finished before Trump took office and it reads quite differently than it probably would have had Kamala Harris won. It’s kind of an interesting head experiment to read it through both lenses, but we are in this lens of Trump having won.

Ezra Klein: One of the questions I’ve gotten a lot in the last couple of days because of things like that CNN segment is actually, what the hell is happening here? Why is this [book] hitting the way it is? The kind of reception and interest we’re getting inside the political system — I’ve been doing this a long time, this is something different. And I think it’s because the sense that if you do not make liberal democracy — and liberals leading a democracy — deliver again, you might just lose liberal democracy, has become chillingly real to people.

And so this world where Joe Biden loses for reelection and his top advisor says, “Well, the problem is elections are four-year cycles and our agenda needs to be measured in decades” — the world where you can say that is gone. You don’t get decades. If you don’t win on the four-year cycle, your agenda is undone and you’ll have serious conversations about what elections look like in the future at all.

Pollan: But a lot of what you’re proposing is going to take a while, building millions of new units of housing.

Klein: No.

Pollan: How do you demonstrate effectiveness within the frame of —

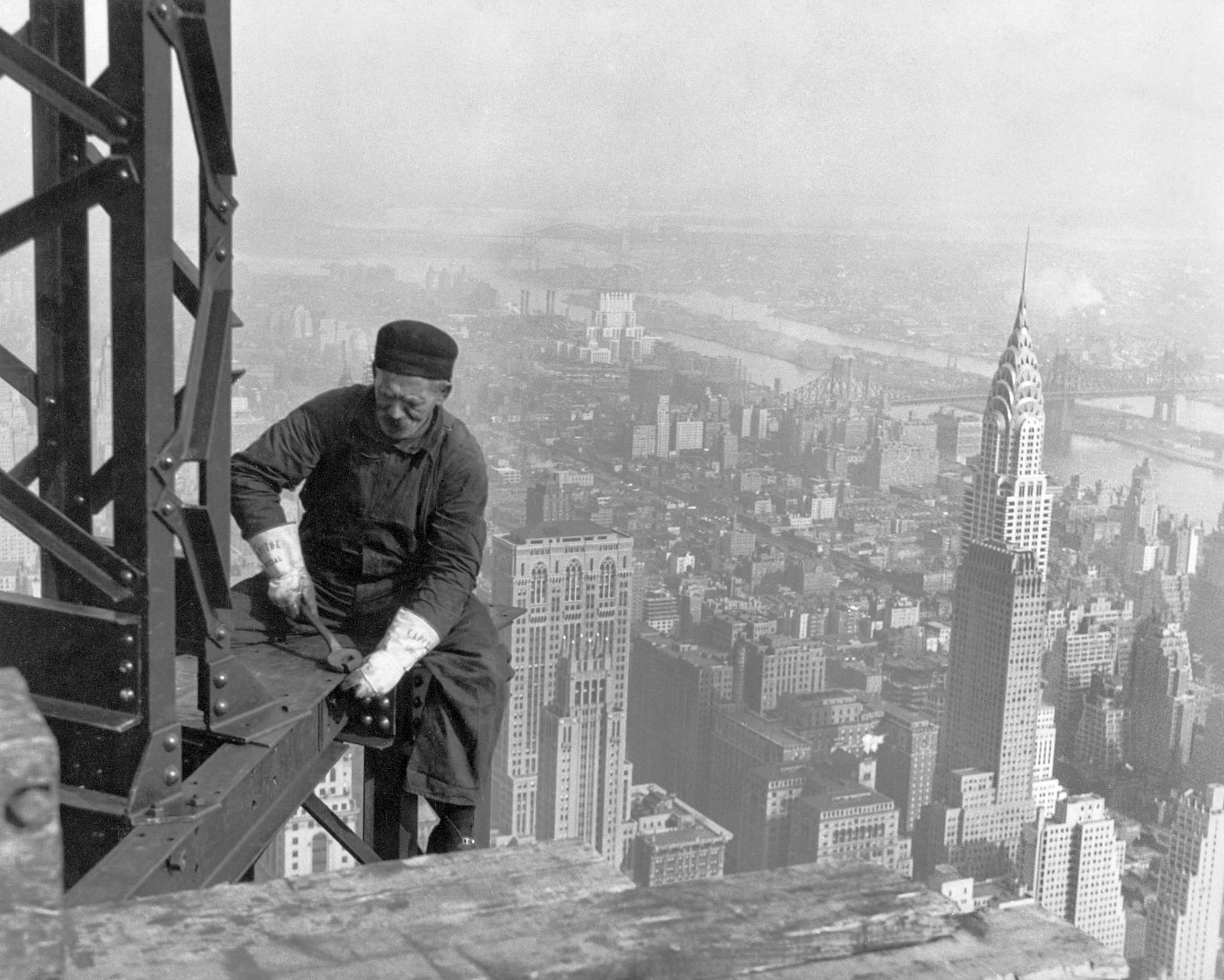

Klein: This is a learned helplessness that we have gotten into. We built the Empire State Building in a year. When Medicare was passed, people got Medicare cards one year later. It took the Affordable Care Act four years. Under Biden, it took three years for Medicare to just begin negotiating drug prices. We have chosen slowness. And in doing so we have broken the cord of accountability in democracy. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill’s median road completion time is 02027. That’s not because asphalt takes six years to lay down. The reason we didn’t get rural broadband after appropriating $42 billion for it in 02021 isn’t because it takes that long to lay down broadband cable. It doesn’t. It’s a 14-stage process with challenges and plans and counter-proposals. We have chosen slowness because we thought we had the luxury of time. And one of the parts of this book that is present, but if I were rewriting it now, I would write it more strongly, is we need to rediscover speed as a progressive value.

The idea that government delivers at a pace where you can feel it? That’s not a luxury; that’s how you keep a government. And so, this thing where we've gotten used to everything taking forever — literally in the case of California high-speed rail, I think the timeline is officially forever. In China, it’s not like they have access to advanced high-speed rail technology we don’t, or in Spain, or in France. You’re telling me the French work so much harder than we do? But they complete things on a normal timeline. We built the first 28 subways of the New York City subway system in four years; 28 of them reopened in four years. The Second Avenue Subway, I think we started planning for it in the 01950s. So it’s all to say, I think this is something that actually slowly we have forgotten: speed is a choice.

We need to rediscover speed as a progressive value. The idea that government delivers at a pace where you can feel it is not a luxury; it’s how you keep a government.

Look, we can’t make nuclear fusion tomorrow. We can’t solve the hard problem of consciousness (to predict a coming Michael Pollan work), but we can build apartment buildings. We can build infrastructure. We can deliver healthcare. We have chosen to stop. And we’ve chosen to stop because we thought that would make all the policies better, more just, more equitable. There would be more voice in them. And now we look around. And did it make it better? Is liberal democracy doing better? Is the public happier? Are more people being represented in the kind of government we have? Is California better? And the answer is no. The one truly optimistic point of this book is that we chose these problems. And if you chose a problem, you can un-choose it. Not that it’ll be easy, but unlike if the boundary was physics or technology, it’s at least possible. We made the 14-stage process, we can un-make it.

The Environmental Questions of our Age

Pollan: You talk a lot about the various rules and regulations that keep us from building. But a lot of them, of course, have very admirable goals. This is the environmental movement. These were victories won in the 01970s at great cost. They protect workers, they protect the disabled, they protect wetlands. How do you decide which ones to override and which ones to respect? How does an Abundance agenda navigate that question?

Derek Thompson: It’s worthwhile to think about the difference between laws that work based on outcomes versus processes. So you’re absolutely right, and I want to be clear about exactly how right you are. The world that we built with the growth machine of the middle of the 20th century was absolutely disgusting. The water was disgusting, the air was disgusting. We were despoiling the country. The month that Dylan Thomas, the poet, died in New York City of a respiratory illness, dozens of people died of air pollution in New York City in the 01940s and it was not front page news at all. It was simply what happened. To live in the richest city, in the richest country in the world meant to have a certain risk of simply dying of breathing.

We responded to that by passing a series of laws: the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Protection Act. We passed laws to protect specific species. And these laws answered the problems of the 01950s and the 01960s. But sometimes what happens is that the medicine of one generation can yield the disease of the next generation. And right now, I think that what being an environmentalist means to me in the 02020s is something subtly but distinctly different from what being an environmentalist meant in the 01960s.

There was a time when it was appropriate for environmentalism to be a movement of stop, to be a movement of blocking. But what happened is we got so good at saying stop, and so good at giving people legal tools to say stop, and so efficient at the politics of blocking, that we made it difficult to add infill housing and dense housing in urban areas, which is good for the environment, and build solar energy which is good for the environment, and add wind energy, which is good for the environment, and advance nuclear power.

We have to have a more planetary sense of what it means to be an environmentalist. And that means having a new attitude toward building.

We made it harder to do the things that are necessary to, I think, be an environmentalist in the 02020s, which is to care for global warming, to think about, not just — in some ways we talk about the tree that you can save by saying no to a building that requires tearing down that tree, forgetting about the thousands of trees that are going to be killed if instead of the apartment building being built over that tree, it’s built in a sprawling suburban area that has to knock down a forest. We have to have a more planetary sense of what it means to be an environmentalist. And that means having a new attitude toward building.

We need to embrace a culture of institutional renewal and ask: what does it really mean to be an environmentalist in the 02020s? It means making it easier to build houses in dense urban areas and making it easier for places to add solar and wind and geothermal and nuclear and maybe even next-generational enhanced geothermal. We need to find a way to match our processes and our outcomes. The Clean Air and Water Act worked in many ways by regulating outcomes. “This air needs to be this clean. This tailpipe cannot have this level of emissions.” That is an outcome-based regulation. What NEPA and CEQA have done is they have not considered outcomes. They are steroids for process elongation. They make it easier for people who want to stop states and companies from doing anything, enacting any kind of change in the physical world, to delay them forever in such a way that ironically makes it harder to build the very things that are inherent to what you should want if you are an environmentalist in the 02020s.

That’s the tragic irony of the environmentalist revolution. It’s not what happened in the 01960s. I don’t hate the environmentalists of the 01960s and 01970s; they answered the questions of their age. And it is our responsibility to take up the baton and do the same and answer the questions for our age, because they are different questions.

Growth, Technology, & Scientific Progress

Pollan: So I came of age politically in the 01970s, long before you guys did — or sometime before you did. And there was another very powerful meme then called “Limits to Growth.” Your agenda is very much about growth. It’s a very pro-growth agenda. In 01972, the Club of Rome publishes this book. It was a bunch of MIT scientists who put it together using these new tools called computers to run projections: exponential growth, what it would do to the planet. And they suggested that if we didn’t put limits on growth, we would exceed the carrying capacity of the earth, which is a closed system, and civilization would collapse right around now. There is a tension between growth and things like climate change. If we build millions of new units of housing, we’re going to be pouring a lot of concrete. There is more pollution with growth. Growth has costs. So how does an Abundance agenda navigate that tension between growth and the cost of growth?

Klein: I’ve not gotten into talk at all on the [book] tour about really one of my favorite things I’ve written in the book, which is how much I hate the metaphor that growth is like a pie. So if you’ve been around politics at all, you’ve probably heard this metaphor where it’s like they’ll say something like, “Oh, the economy’s not... You want to grow the pie. You don’t just want to cut the pie into ever smaller pieces as redistribution does. Pro-growth politics: you want to grow the pie.”

If you grow a pie —

Pollan: How do you grow a pie?

Klein: — which you don’t.

Pollan: You plant the pie?

Klein: As I say in the book, the problem with this metaphor is it’s hard to know where to start because it gets nothing right, including its own internal structure. But if you somehow grew a pie, what you would get is more pie. If you grow an economy, what you get is change. Growth is a measure of change. An economy that grows at 2% or 3% a year, year-on-year, is an economy that will transform extremely rapidly into something unrecognizable. Derek has these beautiful passages in the book where it’s like you fall asleep in this year and you wake up in this year and we’ve got aspirin and televisions and rocket travel and all these amazing things.

And the reason this is, I think, really important is that this intuition they had was wrong. Take the air pollution example of a minute ago. One thing we now see over and over and over again is that as societies get richer, as they grow, they pass through a period of intense pollution. There was a time when it was London where you couldn’t breathe. When I grew up in the 01980s and 01990s outside Los Angeles, Los Angeles was a place where you often couldn’t breathe. Then a couple of years ago it was China, now it’s Delhi. And it keeps moving. But the thing is as these places get richer, they get cleaner. Now, London’s air is — I don’t want to say sparkling, air doesn’t sparkle and I’m better at metaphors than the pie people — but it’s quite breathable; I’ve been there. And so is LA, and it’s getting cleaner in China. And in the UK, in fact, they just closed the final coal-powered energy plant in the country ahead of schedule.

Progressivism needs to put technology much more at the center of its vision of change because the problems it seeks to solve cannot be solved except by technology in many cases.

I think there are two things here. One is that you can grow — and in fact our only real chance is to grow — in a way that makes our lives less resource-intensive. But the second thing that I think is really important: I really don’t like the term pro-growth politics or pro-growth economics because I don’t consider growth always a good thing. If you tell me that we have added a tremendous amount of GDP by layering coal-fired power plants all across the country, I will tell you that’s bad. If we did it by building more solar panels and wind turbines and maybe nuclear power, that would be good. I actually think we have to have quite strong opinions on growth. We are trying to grow in a direction, that is to say, we are trying to change in a direction. And one of the things this book tries to do is say that technology should come with a social purpose. We should yoke technology to a social purpose. For too long we’ve seen technology as something the private sector does, which is often true, but not always.

The miracles of solar and wind and battery power that have given us the only shot we have to avoid catastrophic climate change have been technological miracles induced by government policy, by tax credits in the U.S. and in Germany, by direct subsidies in China. Operation Warp Speed pulled a vaccine out of the future and into the present. And then, when it did it, it said the price of this vaccine will be zero dollars.

There are things you can achieve through redistribution. And they’re wonderful and remarkable and we should achieve them. But there are things you can achieve, and problems you can only solve, through technology, through change. And one of the core views of the book, which we’ve been talking a bit less about on the trail, is that progressivism needs to put technology much more at the center of its vision of change because the problems it seeks to solve cannot be solved except by technology in many cases.

Pollan: There’s a logic there though. There’s an assumption there that technology will arrive when you want it to. I agree, technology can change the terms of all these debates and especially the debate around growth. But technology doesn’t always arrive on time when you want it. A lot of your book stands on abundant, clean energy, right? The whole scenario at the beginning of the book, which is this utopia that you paint, in so many ways depends on the fact that we’ve solved the energy problem. Can we count on that? Fusion has been around the corner for a long time.

Klein: Well, nothing in that [scenario] requires fusion. That one just requires building what we know how to build, at least on the energy side.

Pollan: You mean solar, nuclear and —

Klein: Solar, nuclear, wind, advanced geothermal. We can do all that. But Derek should talk about this part because he did more of the reporting here, but there are things we don’t have yet like green cement and green fuel.

Pollan: Yeah. So do we wait for that or we build and then —

Thompson: No, you don’t wait.

Pollan: We don’t wait, no?

Thompson: Let’s be deliberate about it. Why do we have penicillin? Why does penicillin exist? Well, the story that people know if they went to medical school or if they picked up a book on the coolest inventions in history is that in 01928 Alexander Fleming, Scottish microbiologist, went on vacation. Comes back to his lab two weeks later, and he’s been studying staphylococcus, he’s been studying bacteria. And he looks at one of his petri dishes. And the staphylococcus, which typically looks, under a microscope, like a cluster of grapes. (In fact, I think staphylococcus is sort of derived from the Greek for grape cluster.) He realizes that it’s been zapped. There’s nothing left in the petri dish. And when he figures out that there’s been some substance that maybe has blown in through an open window that’s zapped the bacteria in the dish, he realizes that it’s from this genus called penicillium. And he calls it penicillin.

Left: Sample of penicillium mold, 01935. Right: Dr. Alexander Fleming in his laboratory, 01943.

So that’s the breakthrough that everybody knows and it’s amazing. Penicillin blew in through an open window. God was just like, “There you go.” That’s a story that people know and it’s romantic and it’s beautiful and it’s utterly insufficient to understand why we have penicillin. Because after 13 years, Fleming and Florey and Chain, the fellows who won the Nobel Peace Prize for the discovery of and nourishing of the discovery of penicillin, were totally at a dead end. 01941, they had done a couple of studies with mice, kind of seemed like penicillin was doing some stuff. They did a couple human trials on five people, two of them died. So if you stop the clock 13 years after penicillin’s discovery, and Ezra and I were medical innovation journalists in the 01940s and someone said, “Hey folks. How do you feel about penicillin, this mold that blew in through a window that killed 40% of its phase one clinical trial?” We’d be like, “Sounds like it sucks. Why are you even asking about it?”

But that’s not where the story ends, because Florey and Chain brought penicillin to America. And it was just as Vannevar Bush and some incredibly important mid-century scientists and technologists were building this office within the federal government, a wartime technology office called the Office of Scientific Research and Development. And they were in the process of spinning out the Manhattan Project and building radar at Rad Lab at MIT. And they said, “Yeah, we’ll take a look at this thing, penicillin. After all, if we could reduce bacterial infections in our military, we could absolutely outlive the nemesis for years and years.” So, long story short, they figure out how to grow it in vats. They figure out how to move through clinical trials. They realize that it is unbelievably effective at a variety of bacteria whose names I don’t know and don’t mean grape for grape clusters. And penicillin turns out to be maybe the most important scientific discovery of the 20th century.

It wasn’t made important because Fleming discovered it on a petri dish. It was made real, it was made a product, because of a deliberate federal policy to grow it, to test it, to distribute it. Operation Warp Speed is very similar. mRNA vaccines right now are being tried in their own phase three clinical trials to cure pancreatic cancer. And pancreatic cancer is basically the most fatal cancer that exists. My mom died of pancreatic cancer about 13 years ago. It is essentially a kind of death sentence because among other things, the cancer produces very few neoantigens, very few novel proteins that the immune system can detect and attack. And we made an mRNA vaccine that can attack them.

Why does it exist? Well, it exists because, and this is where we have to give a little bit of credit if not to Donald Trump himself, at least [Alex] Azar, and some of the bureaucrats who worked under him, they had this idea that what we should do in a pandemic is to fund science from two ends. We should subsidize science by saying, “Hey, Pfizer or Moderna or Johnson & Johnson, here’s money up front.” But also we should fund it — and this is especially important — as a pull mechanism, using what they call an advanced market commitment. “If you build a vaccine that works, we’ll pay you billions of dollars so that we buy it out, can distribute it to the public at a cost of zero dollars and zero cents. Even if you’re the ninth person to build a vaccine, we’ll still give you $5 billion.” And that encourages everybody to try their damndest to build it.

So we build it, it works. They take out all sorts of bottlenecks on the FDA. They even work with Corning, the glass manufacturer, to develop these little vials that carry the mRNA vaccines on trucks to bring them to CVS without them spoiling on the way. And now we have this new frontier of medical science.

Left: A mural in Budapest of Hungarian-American biochemist Katalin Karikó, whose work with Drew Weissman on mRNA technology helped lay the foundation for the BioNTech and Moderna coronavirus vaccines. Photo by Orion Nimrod. Right: President Donald J. Trump at the Operation Warp Speed Vaccine Summit, December 02020.

Pollan: Although it’s in jeopardy now. Scientists are removing mRNA from grant applications —

Klein: That is a huge —

Thompson: Total shanda.

Klein: That is a shanda, but also an opportunity for Democrats.

Pollan: How so?

Klein: Because Donald Trump took the one thing his first administration actually achieved and lit it on fire. And appointed its foremost — I feel like if I say this whole sequence aloud, I sound insane — and appointed the foremost enemy of his one actually good policy to be in charge of the Department of Health and Human Services. And also: it’s a Kennedy.

Pollan: I know, you couldn’t make this shit up.

Klein: Look, there is a world where Donald Trump is dark abundance.

Pollan: Dark abundance, like dark energy.

We’re not just hoping technology appears. Whether or not it appears is, yes, partially luck and reality, but it’s also partially policy. We shift luck, we shift the probabilities.

Klein: Yes. And it’s like: all-of-the-above energy strategy, Warp Speed for everything, build everything everywhere, supercharge American trade, and no civil liberties and I’m king. Instead, he hates all the good stuff he once did or promised. Trying to destroy solar and wind, destroyed Operation Warp Speed and any possibility for vaccine acceleration. And you could just go down the line.

And what that creates is an opportunity for an opposition that isn’t just a defense of American institutions as they existed before. One of the most lethal things the Democrats ever did was allow Donald Trump to negatively polarize them into the defenders of the status quo. What it allows now is for an opposition party to arise, yes, as a resistance to what Donald Trump is trying to do to the federal government, but is also a vision for a much more plentiful future. And that’s plentiful, materially, but plentiful scientifically. The thing that Derek, in that beautiful answer, is saying in response to your very good question, to put it simply, is that we’re not just hoping technology appears. Whether or not it appears is, yes, partially luck and reality — whether or not the spore blew in on the heavenly breeze — but it’s also partially policy. We shift luck, we shift the probabilities.

Democrats have these yard signs which have been so helpful for our book. They always say, “We believe in science.” Don’t believe in science, do science and then make it into things people need. We focus a lot in the back half of the book on the way we do grant work and the NIH because it’s really important. No, it shouldn’t be destroyed. No, the scientists shouldn’t all be fired or unable to put the word mRNA in their grant proposals because the people who promised to bring back free speech are now doing Control+F and canceling grants on soil diversity because Control+F doesn’t know the difference between DEI “diversity” and agricultural soil “diversity.”

But it’s also not good that in virtually every study you run of this, the way we do grant making now pushes scientists towards more herd-like ideas, safer ideas, away from daring ideas, away from things that are counterintuitive. A lot of science requires risk and it requires failure. And the government should be in the business of supporting risk and failure. And by the way, we give Democrats a lot of criticism here, but this is a huge problem that Republicans have created and that they perpetuate.

Great science often sounds bizarre. You never know what you’re going to get from running shrimp on a treadmill. We got GLP-1s because somebody decided to start squeezing the venom out of a lizard’s mouth and seeing what it could do. And nobody thought it was going to give us GLP-1s. And they didn’t even realize for a long time really what they had. You need a system that takes science so seriously, that believes in it so much that it really does allow it to fail. And so when Donald Trump stands up there and is like, “We're making mice transgender” — which, one: we’re not. But two: maybe we should?

Pollan: San Francisco answer.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe