Living in Mangrove Time

If we leave the mangroves to grow in their own time, rather than having to endure and be stunted by the pressures of our own, what stories could they tell us?

The memory begins like this: an endless expanse of open water, the cloudless counterpart sky stretching into its own still eternity, the tides’ metronomic rocking against the shell of my sunbleached kayak. There is a prickling warmth of salt spray and heat where my skin would eventually flush pink, burn, and peel. I paddle against that nudging pull taking me out to sea, steadying myself in the suspension of salted spray so I can take in the electrifying verdant bloom of a mangrove canopy and its arching roots which frame the shoreline with intricate buttressing.

I get closer, navigating my kayak into a dead-end tunnel as far as I can go without knocking my paddle against their limb-like wood or getting a faceful of ovular leaves and branches. I float, alone, in a moment of speechless quiet, letting the continuous pulse of the water and the ripple of darting fish and the rustling of startled lizards and cautious birds fill the gaps between my slightly dehydrated breaths. Eventually, I will make my way out of this cool, shaded opening in the mangrove forest and drift back out into the harsh glare of the sun. As I paddle my way back to the sandier, built-out shoreline, the mangroves blur into patterned bands of brown and green suspended between two mirrors of blue.

Nearly half a century before my teenage, sunburnt self made my way into this tangled shoreline, Rachel Carson also found herself along the coast of the Florida Keys with its crocheted mangrove forests and patchwork of rooting tree islands. Her 01955 book, The Edge of the Sea, collected her observations about the mangroves’ resiliency along Florida’s hurricane-battered shore, the tidal migrations of seedlings, and the trees’ role as nurseries for native wildlife. For all of their apparent strength as island-builders, shelters, and anchors of the shore, Carson saw the mangroves’ continued survival as a marginal ecosystem already threatened by rising waters:

“As the years pass, and the centuries merge into the unbroken stream of time, these architects of coral reef and mangrove swamp build toward a shadowy future. But neither the corals nor the mangroves, but the sea itself will determine when that which they build will belong to the land, or when it will be reclaimed for the sea.”

What Carson does not mention: that human action has intervened in the slow timescale of changing tides, leaving the mangrove’s fate on the periphery of Florida’s shorelines still uncertain.

Mangroves are peculiar beings. Unlike their terrestrial counterparts, mangroves are amphibious halophytes, surviving in both salt and freshwater wetlands that would drown and erode other kinds of root systems. Over 50 species of true mangroves have been found around the world although only three—the red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), the black mangrove (Avicennia germinans), and the white mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa)—can be found growing along the coast of Florida. It is believed that mangroves reached the North American continent 66 to 23 million years ago by way of the Atlantic’s Equatorial Current. Very little is known about the life expectancy of mangroves, although it’s estimated that they can probably live up to a hundred years or more. This uncertainty about a mangrove forest’s potential age is unsurprising given that mangroves can remain uniquely undisturbed in stable soil for centuries, have been at the mercy of tidal waters, hurricane-force winds, and shifting coastlines long before humans encountered them (although over a century of various acts of man-made destruction certainly doesn’t make things easier).

A mangrove’s life cycle begins with a reproductive ability known as viviparity. Young seeds can stay attached to the parent tree for over a year while they germinate before dropping into the waters below. These propagules are then swept away by the tides, drifting with the currents until they find brackish water and shallow mud flats to sink into and take root. This stage of growth can last over a year as the finger-like propagule survives on the open water, biding its time for an ideal habitat to spawn in. From there, the mangrove saplings rise, stretching their vascular scaffolding up and out into the water. Juvenile red mangroves can grow up to 5 feet in a single year, a fast rate of growth that has enabled mangrove forests to bounce back quickly from extreme weather events like hurricanes. Compared to other mangrove forests, which have been documented at heights as tall as 80 feet, Florida’s mangroves are often more like thickets of shrubs with black mangroves reaching the tallest heights of 15-20 feet. Over the course of a decade, as more mangrove saplings begin to accumulate, the beginnings of a forest emerge. With their approximate 100-year lifespan and a maturation period of 10-20 years, mangroves’ life cycles and migration patterns surprisingly parallel our own.

Mangroves are able to thrive in these anaerobic environments through their stilt-like system of exposed roots known as pneumatophores by taking in oxygen through these porous, water-repellent surfaces at low tide. Different species of mangroves have developed their own systems to expel the salt in the water they absorb. Red mangroves have built-in barriers that can block 90 percent of salt in sea water from entering their vascular system. Other species, such as the black mangrove, can push salt out through glands in their leaves. As water evaporates, their leaves begin to glitter in the sun with the white crust of salt crystal excretions. Annie Dillard puts it best in her essay ‘Sojourner’: “If survival is an art, then mangroves are artists of the beautiful.”

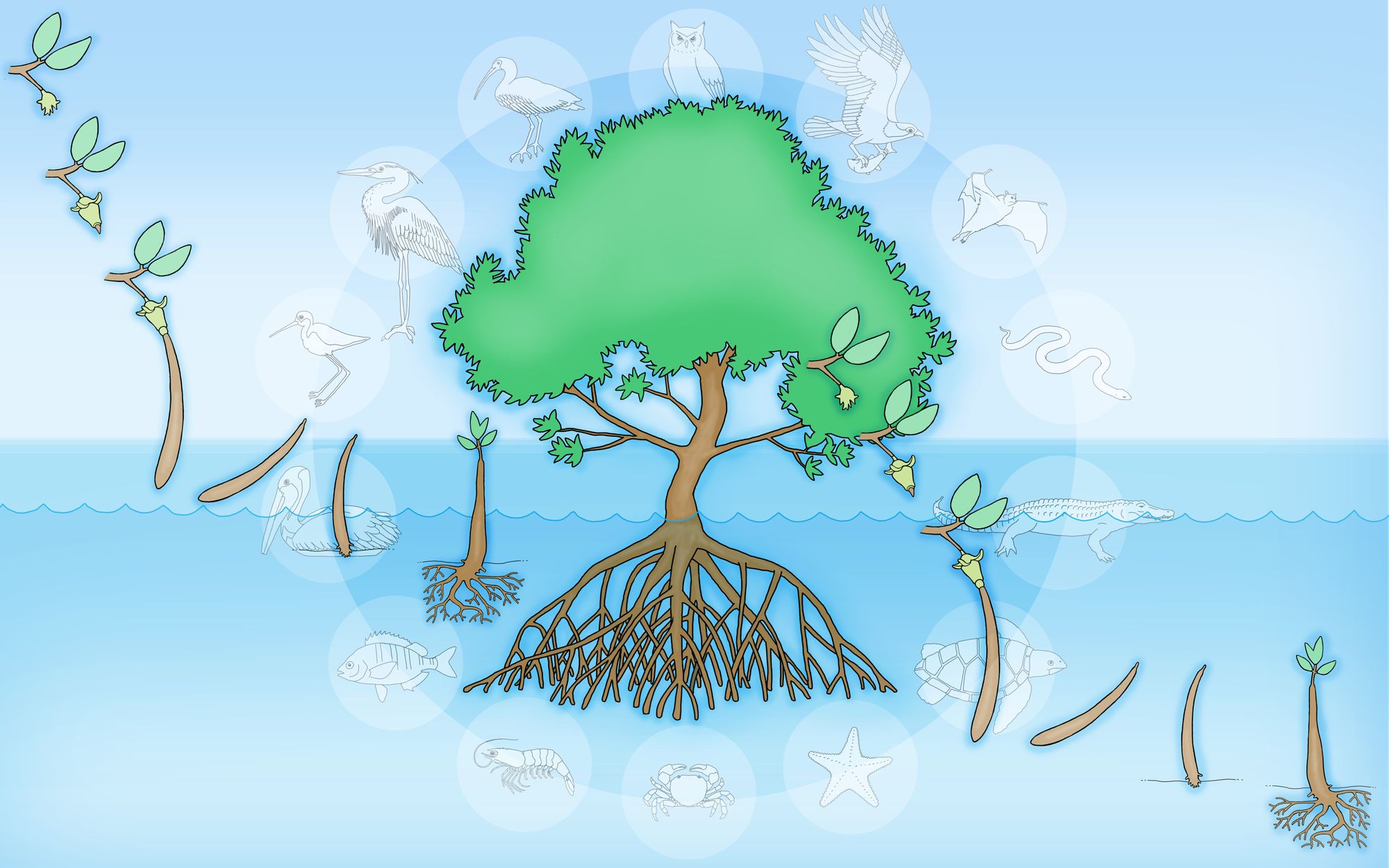

Mangroves have earned many nicknames for their unusual morphology: “walking trees,” “dead man’s fingers,” “snorkel roots.” They’ve also been dubbed the “kidneys of the coast” for their vital role in sustaining coastal wetlands. Thanks to the filtration power of their root systems, they keep the water clear of harmful phosphate and nitrate pollutants, benefitting the corals and seagrasses oftentimes growing nearby. Mangroves act as houses, as kitchens, as cleaners. Give a mangrove forest enough time and creatures begin to take up residence among and on their submerged roots. Oysters contribute to this aquatic clean-up, eventually joined by barnacles, sponges, starfish, and anemones that cling like ornaments to the mangrove’s network of roots. Decomposers like jellyfish, algae, insects, and worms feed on fallen leaves and plant matter, recycling the nutrients of the dead to feed the living. The cagelike structure of this forest is vital for protecting breeding grounds and nurseries for thousands of juvenile marine species such as snook, barracuda, snapper, tarpon, redfish, smalltooth sawfish, crabs, and shrimp. Endangered and vulnerable species such as manatees, dolphins, hawskbill sea turtles, sharks, and crocodiles have all passed through the shelter of these botanical hoop skirts. Above water, the mangroves’ branches have acted as rookieres for migratory and native coastal birds including brown pelicans, herons, roseate spoonbills, kingfishers, cormorants, egrets, and frigatebirds. Even larger mammals like Key deer and Florida panthers have been spotted in this forest of multispecies entanglement. It’s no wonder that mangroves are considered to be some of the most productive and complex ecosystems in the world.

What is less visible to the naked eye, yet vital in the fight against climate change, is the mangrove’s powerful ability to capture carbon dioxide emissions and store them in its carbon-rich soil under the water. Mangroves only comprise about 2% of the world’s marine ecosystems, yet they account for 10 to 15 percent of total carbon burial. This kind of sequestration is known as “blue carbon” and it’s estimated that the mangrove forest’s sink is 4 times more effective at trapping carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses compared to other kinds of terrestrial trees, including rainforests.

Mangroves are the living architects of the shore. Their roots accumulate and retain sediment deposits, building up mud and peat soils that help strengthen and stabilize Florida’s coastal wetlands against erosion. As more species make their way to the mangrove forest, building on its amphibious network of roots and branches, a kind of island can begin to emerge from the shallows where there was once just water. “A society grows,” Dillard muses, “interlocked in a tangle of dependencies.”

On a coastline regularly battered by hurricanes, mangroves can soften the blow of violent winds and the slamming waves of floodwaters by dispersing their force across their intricate root systems. This is not to say that mangrove forests always survive storms completely intact—they are still susceptible to drowning if prolonged periods of flooding and still water cover their exposed roots, and their canopies can still be damaged by high winds and debris—but a study conducted after Hurricane Irma in 02017 found that mangroves prevented approximately $1.5 billion in direct flood damage in their role as arboreal buffer against storm surges. In their essay on the extra-territorial nature of mangroves, Natasha Ginwala and Vivian Ziherl write that “in the intertidal and interpenetrating zone of the mangrove, the border between land and sea becomes a choreography of re-crossings.” Chemical exchanges, interspecies interactions, and dances of hydrology all shape the mangrove forest into a site of porous liminality.

Despite their vital role in supporting Florida’s coastal ecosystems and protecting the state’s human and non-human communities, the mangroves’ existence during the age of the Anthropocene has been one marked by continued precarity.

Long before European colonization, Florida’s mangroves sustained the fish nurseries that fed early Indigenous tribes like the Tequesta on the southeast coast of the Atlantic and the Calusa in the southwest. These forests have seen decades of violent conquest, piracy, and Prohibition-era smuggling along the tip of the peninsula. For 40 years, the mangroves watched as formerly-enslaved fugitives set sail from the coast of Key Biscayne to reach the Bahamas, a voyage now known as part of Florida’s Saltwater Underground Railroad.

South Florida’s rapid urban development in the early 19th century brought about the desire to clear the area’s waterfronts and reroute the movement of water for human benefit. The removal of these mangrove forests took its toll, but so did other more indirect construction projects such as canal systems and dam-building that disrupted the ebb and flow of tides that enable mangroves to thrive. Their roots have suffocated under mounds of sand dredged from Biscayne Bay to reshape the land we now know as Miami. Their pores have choked on the slick sheen of oil spills. Their branches have been cut through to make paths into the Everglades marshland, their wood burned by gladesmen and plume hunters in futile attempts to keep mosquitos away. The mangroves have seen wetlands drained for agriculture, watched housing developments crop up and fill with families, then saw how those flat buildings have gradually been replaced by man-made skyscrapers that reach heights unmatched by any tree. Mangroves may take decades to mature and develop into forests, but their destruction takes just mere minutes.

It’s been estimated by local researchers that 86% of Florida’s mangrove coverage has been lost since the 01940s. Between 02000 and 02015, a study found that, globally, the destruction of mangrove forests released 122 million tons of stored carbon into the atmosphere. It wasn’t until the Mangrove Trimming and Preservation Act was passed in 01996 that it became illegal to destroy or damage mangroves outside of already-protected parklands and aquatic preserves. Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection now estimates that 600,000 acres of mangroves line the state’s shores, although its waters once spawned millions. Yet mangroves are still not entirely safe from the threat of destruction in the name of human development. Even after this year’s summer kicked off with severe flooding across Miami from heavy rains (an occurrence that has become increasingly frequent), one of the city’s commissioners proposed an ordinance to ban the planting of mangroves in city parks in order to “protect waterfront views.” Although the proposed ordinance was eventually withdrawn after public protest, it symbolizes a view many still have about mangroves—that they are still impeders of urban progress, despite the fact that Florida’s commercial fishing and marine-based economies would collapse without them, and that mangroves may be the key to Miami’s long-term coastal resiliency.

In 02018, Miami-based photographer Anastasia Samoylova stood on the shores of the Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve and captured an image of what she saw, later becoming part of her series, FloodZone. In the distance, you can see the stilted ruins of the Cape Romano Dome House’s modular, science-fictional structure, a once self-sustaining home on the water that has since been reclaimed by sea gulls and pelicans as nesting grounds. At the foreground, a ghost forest of a deceased mangrove thicket stands on the sandy shore like spindly skeletones, their gnarled bone-white forms contrasting the smoother, more rotund manmade structure. This photo has stayed with me as a reminder of what’s at stake in these acts of mutually-assured destruction as rising waters threaten to drown everything around us.

If we leave the mangroves to grow in their own time, rather than having to endure and be stunted by the pressures of our own, what stories could they tell us? What lessons of resiliency might we find among their storm-breaking, nourishing roots? Mangroves are not so different from humanity, after all. They mature in the same two-decade period as we do. They, too, adapt their root systems to meet the unique needs of the brackish or saltwater coasts they grow along. Like us, they let their children out into the world, with all of its promise and danger, and hope that the next generation will find a place where they’ll be able to put down their roots and thrive.

The understanding that trees have the capacity for migration is nothing new, yet the mangroves’ movement further up into Florida’s northern coasts and increasingly into more inlands are key indicators of climatic shifts in temperature and sea-level rise that already have and will continue to greatly impact the ecosystems we rely on to survive. Nowadays, many frontline coastal communities in South Florida and beyond are grappling with an existential challenge: keep the water at bay or begin to plan a managed retreat and scatter into an unknown future.

Already, the mangrove’s unique arboreal design has inspired speculative projects and models of infrastructural biomimicry. In 02016, Taiwanese designers Sheng-Hung Lee and Wan Kee Lee unveiled their TetraPOTs, a kind of interlocking coastal defense made of interlocking submerged planters for mangrove saplings to take root in, and Syracuse University-based architecture firm APTUM debuted Rhizolith Island, a concrete breakwater island meant to aid the repopulation of mangrove forests. In 02019, researchers at Florida Atlantic University proposed modifying existing seawalls with mangrove-like cylindrical paneling. In 02020, researchers discovered a way to desalinate water through a kind of synthetic, silica mangrove root that replicates the trees’ porous filtration. Most recently, scientists at the University of Miami have proposed a replacement to the stony riprap found at the base of the city’s sea walls. Dubbed SEAHIVE, this stacked structure of hollow concrete tubes is a marine and estuarine shoreline system designed to dissipate the energy of incoming waves like mangroves and reefs do (and will eventually include its own crop of saplings and planted corals). Where seawalls alone fail in their inefficient, breachable, pollutant, resource-exhausting concrete simplicity (one recent estimate put the cost of raising and repairing Florida’s existing walls at $75 billion to meet the coast’s projected 2 foot sea-level rise by 2060), living shorelines—particularly mangrove-lined ones that can eventually spawn other coastal life—offer innovative alternatives that connect, rather than divide, us from Florida’s local biota and work with the life-cycles of native flora and fauna and local hydrology rather than trying to block them.

Replanting efforts by local environmental groups take place every year up and down the coast, although they vary in their ability to successfully respawn and build new forests. Some sapling replanting projects only boast a success rate of 50% or less. Decisions like planting in an area without the proper intertidal hydrology or putting certain species on land masses and in depths where they have not historically thrived can lead to hundreds and thousands of dollars and local resources wasted. Frequent shore-battering weather events and proximity to continued human activity don’t improve their chances either.

Wetland scientist Robin Lewis has become world-renowned for his mangrove restoration techniques. His strategy is simple: think like a mangrove. Immersing himself in the dynamism of each unique coastal habitat, Lewis watches the water to find the best balance of high and low tide for each species. Sometimes humans have to create ideal conditions where there are none by adding slopes of dirt to ocean shallows and dismantling man-made blockages to bring back natural waterflows. While bulldozers are far less charming than neat rows of seedlings, oftentimes these mangrove forests end up doing the work of replenishing themselves as their propagules find their way to the newly-restored intertidal shores.

How might we embrace the mangroves’ beautiful periphery? What does it mean to shift our thinking away from the short-term, profit-driven interests of accelerated economic growth and embrace a long-term living with the mangroves and all of their delicate, yet strong, restorative ecology? As Ginwala and Ziherl observe, in mangrove time, “human traces cannot survive as a lasting form, for this tropical coastal ecology is a site of continual refiguration.” Already, rising waters threaten many of Florida’s coastal communities. The old ways of measuring the success and health of a community are becoming increasingly absurd and outdated in this time of climate emergency. If we do not give mangroves a chance to truly thrive on our shores and live alongside us, they risk drowning in a matter of decades too.

Ecocritical scholar Jeffrey Jerome Cohen has this idea of “long ecology,” a kind of ecological understanding that “exchanges human life spans as familiar units of counting for more profound durations” and embraces a “more-than-human temporal and spatial entanglement” which brings with it “an affectively fraught web of relation that unfolds within an extensive spatial and temporal range, demanding an ethics of relation and scale.” Considering new temporal protectives is something anthropologist Erin Fitz-Henry also urges, writing that we must “tune back in'' with a scope “as much toward ancient pasts as toward distant futures, according to speeds and rhythms both fast and slow” as this “might allow us to listen more closely to the full range of temporalities with which we are surrounded.” Perhaps living like mangroves will help us listen, to restore an ecological understanding that we have spent centuries unlearning. As Carson notes, the sea may ultimately decide our fate, but we should see mangroves as our kin as we collectively choose how to proceed, intertwined, into Florida’s amphibious future.

On my way to work, now thousands of miles away from the Florida coastline and years after that first kayak trip out into the mangrove forest, I’m listening to an episode of NPR’s Short Wave as I squeeze myself into the throng of morning commuters. Trying to ignore a stranger’s backpack digging into my arm and the way my skin’s already sticky with sweat during this heatwave, I listen to Dr. Alex Moore—a professor and researcher who specializes in coastal wetland ecosystems—liken mangroves to a city for all of the aquatic and terrestrial animals living among its roots and branches.

I emerge from the crowded subway out into the new city I call home. I, too, have drifted with the tides and dug my sapling roots into new soil. I take in the air, wet and soft with the familiar density of humidity, and think about how this land has been designated by climate scientists as subtropical. For a moment, I do not hear the sound of honking cars, nor the chatter of crowds passing by, only the slow, gentle rhythm of waves lapping against a metropolis of submerged root systems slowly stretching out their fingers into the ocean’s eternal unstillness.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe