Am I Slop? Am I Agentic? Am I Earth?

Identity in the Age of Neural Media

Neural Media

Over the last decade, I’ve watched AI challenge — and augment — humanity in astonishing ways. Every few years, a new innovation seems to raise the same questions: can we compute human intelligence? Can our labor be automated? Who owns these systems and their training data? How will this technology reshape society? Yet there is one question I rarely hear asked: how will AI change our understanding of ourselves?

All media influence our sense of identity. In a previous essay, I examined how older media types altered subjectivity, in deliberate and unforeseen ways, and developed an evolutionary framework of media types. It begins with broadcast media (such as radio and television), which were molded into immersive media (from museum exhibitions and laser shows to Burning Man and VR), and later network media (from home computing to social media, short-form video, and memes). AI appears last, in a new category I called “neural media,” which also includes any medium that incorporates neural structures, such as brain-computer interfaces.

The purpose of this framework was to compare and contrast historical media types through the space, content, and identity they produce. I described an increasing fractalization of identity made possible by more complex and recursive methods of audience sensing. The demographic blocks that describe television viewers (age, gender, race, location) are crude compared to the AI embeddings that adtech systems use to describe today’s web users. Online political identity now has many facets and variations that do not easily map to a 20th century two-party system or left-right spectrum.

In the words of Marshall McLuhan, “The content of any medium is always another medium.” In my framework, media types mature — and consume their predecessors — in 30-year phases. In the early 02010s, we began to feel the effects of the mature network media form, just as neural media appeared.

We are now, in 02025, 15 years into neural media, halfway through its maturation cycle. That is to say, neural media are still relatively malleable. Given that they will have profound effects on every aspect of culture and subjectivity, it’s imperative that we address them as a psychosocial force, before their structures become fixed. How we do this will determine neural media’s influence on 21st century identity.

Embedded Identity

Media shape identity and subjectivity through feedback loops. Twentieth century broadcasters, in pursuit of accurate advertising targets, used devices like the Audimeter to measure viewer demographics. This information allowed broadcasters to produce content that appealed to, and shaped, specific groups of viewers. In a media environment built with AI, human users are perceived and reflected not through demography but through statistical distributions. In the same way that programmed television shows reinforced demographic aspects of identity, neural media reinforce identities as they are perceived by machines, that is, as locations (or embeddings1) in a statistical landscape.

Every interaction we have with AI involves being seen, interpreted, and reflected through this hidden landscape or latent space. For example, imagine a credit system that uses AI to assign scores to borrowers. This reduces a complex data set (my credit history) to a single number, which can drastically alter my ability to rent or buy a home. Similarly, my driving behavior, as measured by computers in modern automobiles, is ingested by machine learning in order to predict accidents and determine my insurance rate. Social media algorithms control what I see in my feed, and how my personal profile is exposed, with downstream effects on my social life, politics, and employment.

Many dimensions of daily life today are determined by one’s position in an AI model’s latent space. These perceptions have material consequences that inevitably influence my sense of self, even if I disagree with them. In a world increasingly run by AI, we navigate both physical and latent space simultaneously. So it’s increasingly important that we understand what it means to identify as an embedding in a statistical model.

Being Statistical

One need not look far for examples of embedded and statistical self-identification in culture today. Dating app users describe themselves in terms of percentiles and distributions. ("I'm in the top 20% for height.”) Social media platforms provide statistical metrics for one’s online profile. ("My engagement rate is in the top 10%.”) Personality systems, like the MBTI, Big Five, or Kegan scale — not to mention popular astrology and derivatives like Human Design — encourage people to discuss their own traits within statistical distributions. (“INTJs make up about 2% of the population, while manifestors make up 9%.”) Fitness tracking via biomarkers and wearable devices provides a statistical frame for both physical and social identity, and new psychological theories describe states of mind in topological terms.

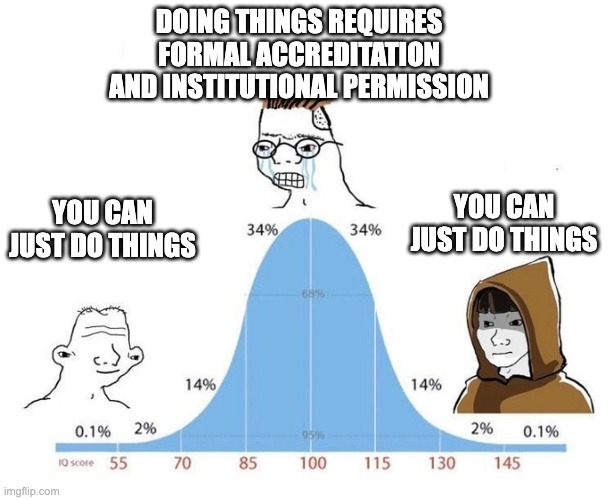

While it’s clear that the statistical model of subjectivity is already present and influential, specific statistical terms and concepts remain opaque to the average user, with a few exceptions, notably the bell curve. A bell curve is a visual rendering of the “normal distribution.” Its mean, median, and mode are all equal, and occur at the center of the distribution, producing the signature symmetrical bell shape. The bell curve has been used for financial analysis, psychometry, and medicine, but also as a justification for racist ideas about human intelligence.

Such uses of the bell curve are satirized in a popular meme format, in which an idiot and a genius occupy the curve’s far ends. They share the same simple opinion on a topic (e.g., “You can just do things”). Both disagree with a third character, the midwit perched atop the curve. Unlike both idiot and genius, the midwit is mired in ideology and overthinking (e.g., “Doing things requires formal accreditation and institutional permission”). This meme humorously indulges in Ken Wilber’s pre/trans fallacy (in which pre-rational intuition is equated with transcendent post-rational insight) to express the normie’s contemptible position in the normal distribution. To the knowing insider (and the terminally online), “mid” always equals bad.

Being mid

The slang term mid is now used to refer to anything of middling or mediocre quality, the most commonplace artifacts and opinions one finds at the center of the normal distribution. The term originates in cannabis grades; mid refers to strains that are neither strong nor weak. Mids could be seen as inferior products. Yet in a newly legal cannabis market, characterized by an arms race of cultivation, a mid experience might be preferable to one optimized for competitive metrics like THC content. The term mid entered circulation and was applied to other subjects like attractiveness and aesthetics, becoming a useful handle on the statistical self-image experienced by embedded subjects.

The most potent embodiment of mid-ness might be what is now called “AI Slop.” The term describes the default content generated by AI models. AI slop is hard to pin down, but like pornography, you know it when you see it. Like a fast casual food bowl, mass market action movie, or fabricated pop diva, AI slop is made to please the largest possible audience, yet satisfies no one. It prioritizes its economic function above all else, filling a void with minimum viable content, ignoring any aesthetic, nutritive, or meaningful possibility.

Fortunately, we can define AI slop in somewhat more precise technical terms, because it originates at the center of a bell curve, specifically the bell curve used to optimize VAEs, or variable auto-encoders, the underlying architecture of early AI image generators. In order to smooth the distribution of data and ensure consistent images, VAEs conformed data sets to a normal distribution during training, resulting in the visual language of early GAN art.

Language models are based on probabilities, and they also default to slop. The LLM property called temperature controls the range of acceptable probabilities for selected next tokens (tokens are roughly equivalent to words). A low temperature setting produces only the most predictable language. At a high temperature, outputs are random, surprising, sometimes chaotic or confusing. Just like AI image generators that hallucinate the most common image associated with a prompt, LLM base models generate content at the mean, the metaphorical peak of the curve. In other words, they are built to be mid.2

We might be tempted to call these midpoint representations of objects and ideas iconic or archetypal, but they are not. Iconic imagery is powerful because it is specific. The broadcast images of the 20th century achieved iconicity in specific times and places. Historic turning points were captured in images broadcast worldwide in realtime. The sudden psychic imprint of a broadcast image might evoke an archetypal pattern beyond a specific moment or culture. Think of the Hindenburg disaster and Icarus’s melting wings, or the lone protestor in Tiananmen Square and David fighting Goliath, the falling Twin Towers and the Tower card in a Tarot deck. In contrast to iconic specificity or archetypal resonance, hallucinated content is a synthetic blur of training data absorbed into a latent attractor. While the default face or color palette learned by an image generator might be attractive, it is by definition, mid. This kind of midness is the source of AI slop’s distinctive blandness, and a strong, unacknowledged force in contemporary aesthetics.

Being slop

Generative image systems have iterated from primordial chaos to a convincing, often boring, photorealism. DeepDream had its dogslugs, while early versions of DALL-E and Midjourney had six-fingered hands and melting faces (glitches that ironically now provide a unique timestamp and cultural context). These errors have been mostly corrected in state of the art models. But they persist in the low-cost and open-source models used by social media spambots.

Top Left: DeepDream show at Gray Area. Top Center: Jorōgumo by Mike Tyka. Top Right: Image by Merzmensch. Bottom Left and Bottom Right: Images collected by Insane Facebook AI Slop.

The output of these spambots has been called “gray goo” after Bill Joy’s runaway nanotech scenario. While this is evocative (and brings with it a longer history of speculative tech doom) I prefer to think of these images as a subgenre of AI slop. Gray goo is perfectly uniform and evenly distributed, while slop is disturbingly chunky and uneven. It is visceral and messy. Objects melt into each other. Text prompts bubble up through images, garbled and out of place.

Slopbots are usually aimed at the widest target on the social graph. In the case of the above example, this graph belongs to Facebook. By targeting the peaks of Facebook’s social and political distribution, bots distill sentiment, ideology, and aesthetics into a hardcore AI slop that is nostalgic, jingoistic, absurdly pro-natal, and militantly religious. More associative than meaningful, it operates below the threshold of conscious awareness, acting as a subliminal stimulus for farming attention, and for nudging an amorphous body politic. The largest audience for these memes might themselves be bots.

This is the critical question we must ask ourselves as we pass through the halfway point of neural media’s 30-year maturation: how might we avoid becoming bots, becoming mid, becoming slop? Online contrarians that circulate bell curve memes reflexively see themselves as the genius on the far right. Unswayed by the mid, the superior wizard sees through the dense statistical center. But they too are subject to embedded identity. In a neural media environment, one’s agency is measured by the ability to construct oneself despite, against, or alongside one’s embedding.

Being agentic

Millennials and zoomers, having grown up online, may believe themselves immune to the persuasions of slop, but they are not. Apps like Character.AI already provide lonely users with chatbot approximations of emotional and sexual intimacy, sometimes with disastrous results. When AI hallucinations achieve VR immersion and realtime interactivity, users will be exposed to ever more subtle manipulation. Whereas previous media forms relied on suggestion, emerging forms in neural media presume to one day act on behalf of users. In such an environment, agency becomes the target of not just manipulation but automation. Like the double agents in Philip K Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, actors in agentic neural media ecosystems can never be sure of their own motivations.

Recently, the AI industry has focused on building and promoting features that might one day stack up to personalized AI agents. OpenAI, Google, Microsoft and Apple have all announced AI features like voice interaction, screen recording and understanding, and private on-device AI memory, drawing the silhouette of a future AI agent that understands everything you do, and acts on your behalf. These product concepts floated around for a decade or longer, and their appearance at launch events in the last year is a testament to the consistency (or insularity) of corporate AI UX discourse.

These ideas existed before AI alignment was a common concern, and their persistence suggests that designers prefer to solve alignment through personalization. In other words, we don’t need an AI oracle with one perfect answer to every question, but an infinitely customizable AI agent aligned with each individual user, acting on their interests, as represented by an embedding.

Seen through the lens of AI slop, agent personalization is a way to refine default mid outputs into something contextually meaningful. Filtered through a personal history of interactions and objectives, specifically relevant outputs are promoted over default responses. Systems like this may be even more capable of manipulation, with their privileged access to user needs and personal data. It’s easy to imagine perfectly sloptimized media products designed to manipulate groups of users, individuals, or even sub-personae within an individual psyche.

This is where human agency grapples with embedded identity. As I move through latent spaces, I exert agency by resisting, accepting, altering, or recontextualizing the embedded identities created for me. This is the simpler, pre-agent form of embedded neural media identity. If AI agent personalization is taken up by users, we can expect an even more complex relationship with agents and with agency itself.

In a world of hallucinated content, AI agents act as memetic membranes, filtering and contextualizing AI slop, producing new vulnerabilities and dependencies. An AI agent that surveils what I do and acts on my behalf will change how I resist or accept embedded identities. Such an intimately hybrid, human-AI selfhood may not even be consciously experienced. This situation could be empowering, vampiric, or symbiotic. Such perceptual-adversarial relationships form the bootstrap of much organic evolution, suggesting that future, post-neural identities will emerge on either side of this human-AI agency exchange.

Being Earth

We are addressed by neural media platforms as individuals. We log into social networks and AI chatbots as single users, using personal devices. But humans, and individuals, are not the only possible subjects of neural media. An emerging field of remote-sensing and Earth-oriented foundation models are now enabling machine perception at planetary scale. Weather patterns, animal migration, forest fire and flood behavior, and the dynamics of human populations, are converging as linked latent spaces. Systems like these are always ambivalent: a neurally visible Earth could force us to acknowledge the very ecological relations we now ignore. It could also lead to total capture of terrestrial space.

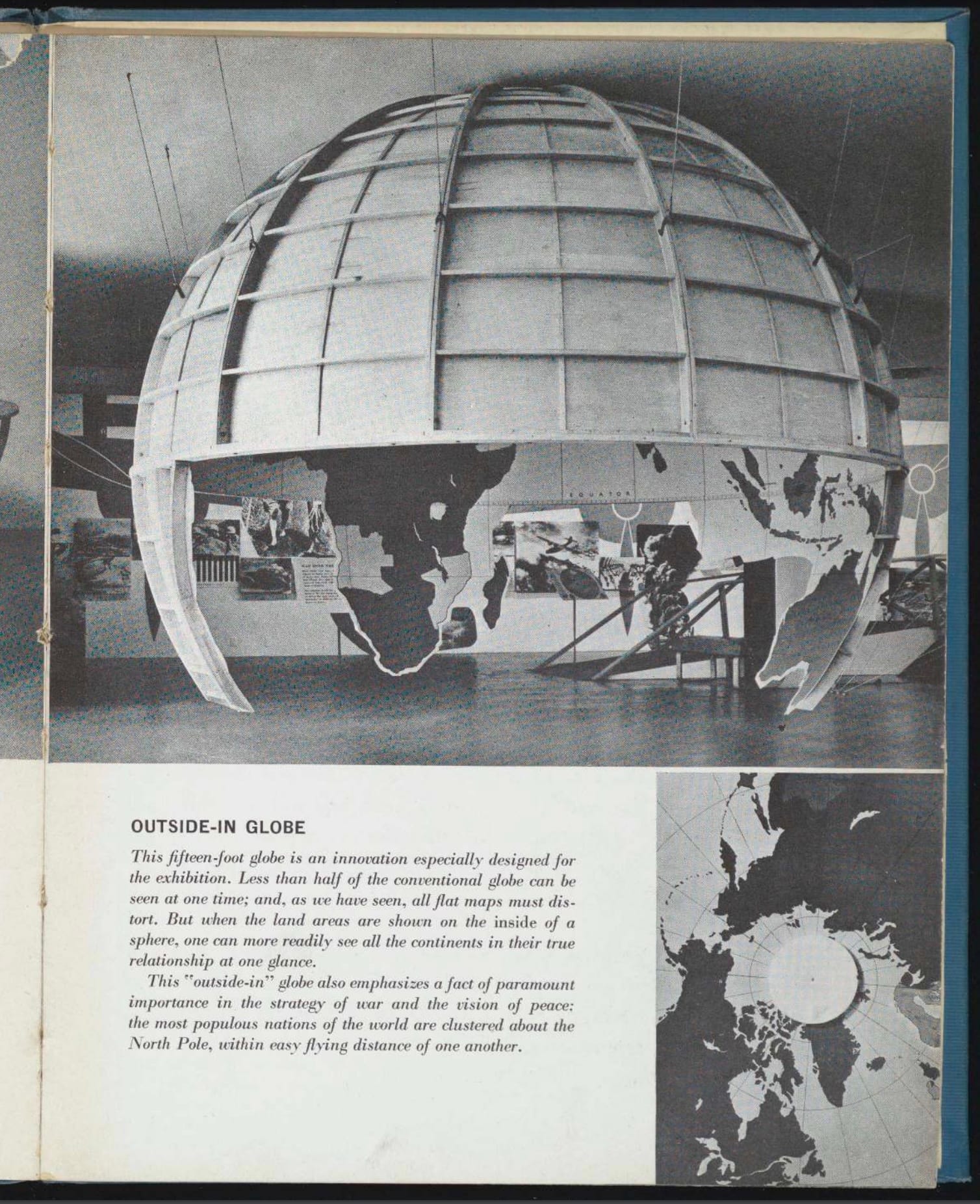

This ambivalence toward nature and containment is mirrored in the architectural form of the dome. Domes appear throughout the history of media, from the “outside-in globe” presented at MoMA’s 01943 Airways to Peace exhibition to America’s World’s Fair pavilions, as a symbol of off-grid autonomy in Drop City and the Whole Earth Catalog, and as the ultimate immersive architecture defining MSG’s Las Vegas Sphere. The total AI view of Earth is the largest conceivable dome, a high-dimensional, virtual space in which nature’s mystery is revealed, as we merge back into the ecosystem via computational gnosis. It is also the final enclosure, wherein any transcendence of media is already anticipated by an Earth AI that has mapped every possible line of flight.

Left: Page from Airways to Peace: An Exhibition of Geography for the Future (01943). Center and Right: Pages from the Whole Earth Catalog (01968).

In both cases, Earth-focused AI models provide a non-human latent space in which to experience embedded identity. Seeing oneself within the statistical distributions of social media is fundamentally anthropocentric, even narcissistic. But multispecies latent spaces provide a larger perspective, in which homo sapiens sapiens is just one embedding in a patchwork of diverse intelligence.

Triangulating between humans, non-humans, and AI, we glimpse a prismatic, rather than mirror-like, relationship with neural media. In the jewel of all possible minds, we are one facet containing other facets. When we recognize this we cannot help but acknowledge our dependence upon other beings, whether those be gut bacteria or beavers and wolves who shape rivers, transforming ecosystems and landscapes. Their survival becomes our survival. Planetary-scale ecological challenges like climate change and biodiversity loss are crises not of information but of coordination. Perhaps, a multispecies identity refracted through Earth-sensing neural media could shift the underlying assumptions that keep us from seizing ecological agency. Shouldn’t we demand a latent space for collaboration between humans and non-humans?

Notes

1. The term "embedding" comes from machine learning. It describes a location in a mathematical space where properties of objects are learned and compared. This continuous vector space compresses a large data set into a high-dimensional manifold. In this latent or hidden space, two objects’ distance reflects their similarity or difference. The distribution of points in a data set — and how they cluster in a model’s latent space — can be modeled statistically. This statistical distribution can be imagined as a landscape; areas where many similar examples co-exist become valleys, attractors, or local minima in the space.

2. But what if being mid isn’t so bad after all? It turns out that when you ask the leading language models to name their favorite colors, they all converge on roughly the same shade of blue. Since AI models don’t have favorites (see the chain of thought transcript for proof of this) they choose their favorite color based on statistical preferences. Language models are compelled to answer, so they role play the default human, who prefers the color of a clear blue sky. Who wouldn’t?

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe