If you want to know what the climate might be like one or two centuries from now, talk to a climate scientist. If you want to know what it’s like to live in a world transformed by these changes, your best bet is to talk to a climate fiction writer.

Climate fiction — referred to as “Cli-fi” by its fans as a play on Sci-fi — is relatively new as a coherently defined genre. While stories of environmental disaster are at least as old as ancient foundational flood myths in China and Mesopotamia, and stories specifically naming climate change as a driver of plot go back at least as far as J.G Ballard’s 01964 novel The Drowned World, climate fiction as a category is no older than a decade and a half. Originally coined by journalist and writer Dan Bloom in the late 02000s, the term reached a broader audience in the early 02010s as a number of prominent authors including Kim Stanley Robinson, Margaret Atwood, and Barbara Kingsolver wrote novels exploring the social ramifications of climate change and ecosystem collapse.

As a style, climate fiction takes many forms. In some novels, like Richard Powers’ 02018 Pulitzer-winning novel The Overstory, concerns about ecological destruction seep into the milieu of realist literary fiction; they’re set in worlds much like ours, with environmental issues and politics to match. Others, like Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (01993), are set in the near future in moments of societal collapse, investigating the social ramifications of continued warming. Still others, like Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home (01985), are set far after our time, exploring the long tail ecological effects of the current climate crisis.

Much of the attention around climate fiction focuses on its potential as a tool for moving people otherwise apathetic about climate change to take action, painting the climate novel as a sort of moral instruction or grim warning. These are stories that can “save the world” — or, at least, leave us “frightened into action." Some of the most acclaimed books in the style make this claim explicitly. In The Overstory, one character pins the blame for ecological devastation at least in part on a lack of good climate stories, saying, “The world is failing precisely because no novel can make the contest for the world seem as compelling as the struggles between a few lost people.” In this view, climate fiction is a sort of clever substitute for documents like the reports generated by the IPCC (the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), a more immediate form of communication compared to thousands of pages of dry scientific bureaucracy. If climate change must fight in the attention economy against pop culture and passing political news, it only makes sense to give it equally sharp weapons.

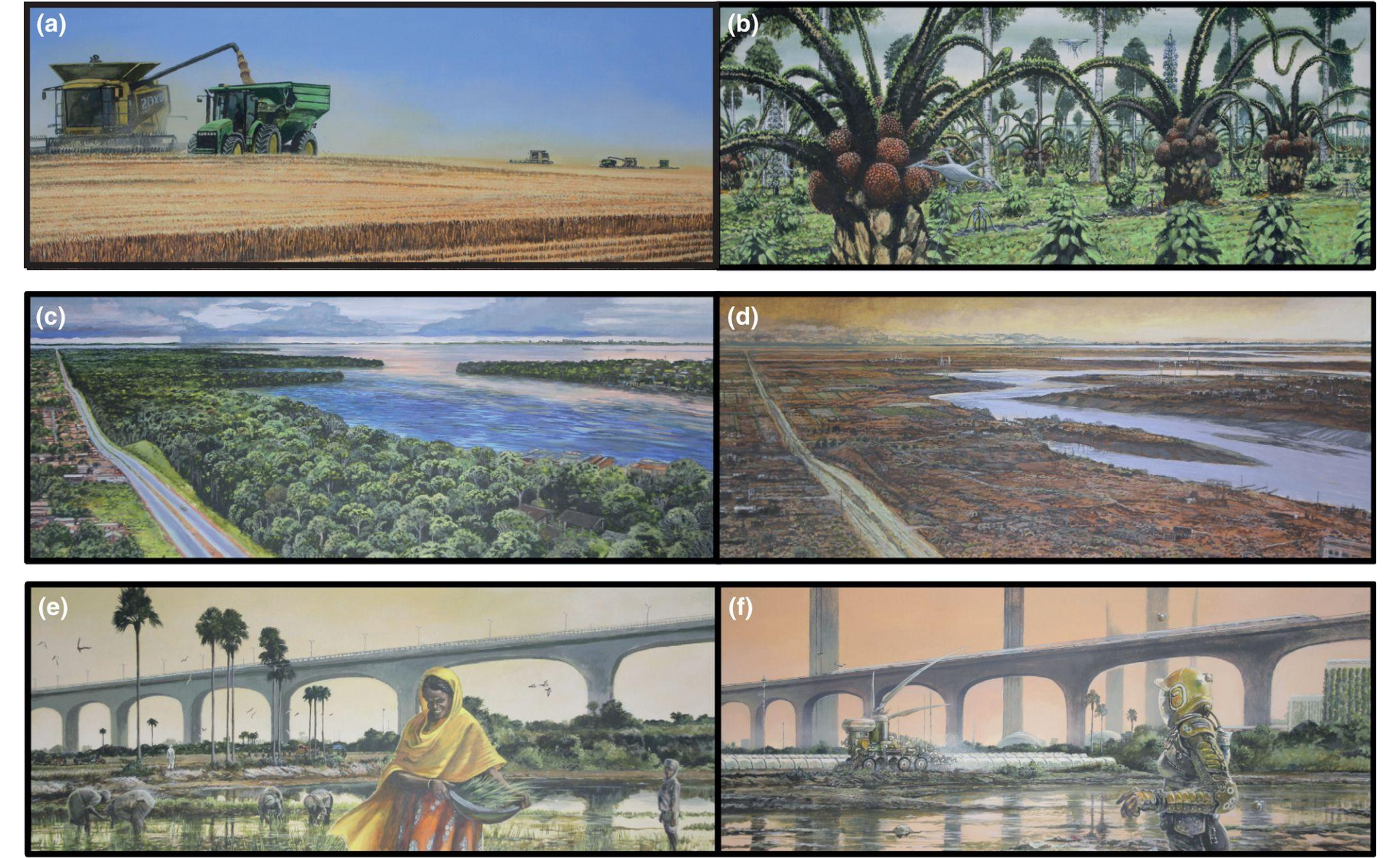

Yet portraying climate fiction as such undersells its value to society. The best climate fiction can do more than spur us to action to save the world we have — it can help us conceptualize the worlds, both beautiful and dire, that may lie ahead. These stories can be maps to the future, tools for understanding the complex systems that intertwine with the changing climates to come.

Maps to the Future

For some involved in climate activism, climate fiction provides a helpful way to focus on the long-term. When Tory Stephens, the Climate Fiction Creative Manager and Network Weaver at Fix, the Solutions Lab associated with climate news site Grist, first became involved in climate justice work, his focus was on “short term wins” like policy changes that would directly address environmental ills in the span of months. Getting more deeply involved with climate fiction through starting Fix’s Imagine 2200 short story contest allowed Stephens to realize that “even if you are looking at a problem for now, it helps pull you outside your comfort zone to even dream expansively around lots of alternatives.” To Stephens, just the process of “entertaining those [visions of the future] opens your mind.”

Imagine 2200’s vision of the future is one deeply shaped by long-term thinking, Stephens told Long Now. The project asked for climate fiction short stories that imagine pathways to “clean, green, and just futures” by the year 02200 — a year chosen not just for its anagrammatic resemblance to 02020, the year the idea for the contest emerged from, but for its particular distance from the present. In Fix’s view, 02200 represents a point seven or eight generations out from the present, using a commonly invoked principle of intergenerational stewardship based on Iroquois principles of governance. When you think about climate futures using the view of the next two centuries, Stephens noted, you enter the mindset of being a “good steward for future ancestors.”

That vision of good stewardship is reflected in the stories featured in Imagine 2200’s collection. While many of the most prominent works of climate fiction in the popular consciousness are grim visions of a future bereft of good stewardship — think Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (02006) or Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus (02015), set in worlds overcome by disorder and selfishness following ecological collapse — Imagine 2200’s future worlds are more hopeful in the face of disaster. In “Afterglow,” the winning story of 02021’s contest, a secret order of “Keepers” attempt to revitalize our planet based on “a way of being that has been present on Earth for thousands of years.” While the particular set of climate solutions portrayed in each individual story is unique, the overall ethos of the collection is distinctly anti-apocalyptic. The current order may be overturned and the crisis may overtake us, but these stories propose that even after catastrophe survival and renewal is possible.

Complex Systems

Climate fiction’s greatest advantage as a style may be its ability to articulate both disaster and rebirth with clarity. In novels like New York 2140 (02017) and The Ministry for the Future (02020), Long Now Speaker Kim Stanley Robinson grounds the stakes of his story in real scientific details — sea level rise, wet bulb temperature events, and more plausible disasters. In contrast to other science fiction stories, which often rely on salvation from singular chosen one-type figures, Robinson’s stories also serve as paeans to the power of collective action.

Stanford Professor Jamie Jones, who spoke at the Interval in 02019 about the science behind climate fiction, cited Robinson’s work and the power dynamics within as especially powerful in an interview with Long Now. Jones noted that “those stories are really great in the sense that he doesn't shy away from talking about the seriousness of the consequences. But [in his stories] people solve their problems and they do it the way actual problems get solved: through teamwork, cooperation and sacrifice.”

Jones’ primary research focus is in complex systems — the nonlinear dynamics that explain epidemiology and human social networks. In climate fiction, and especially the more sci-fi leaning portions of the genre, Jones sees the potential to model the complex systems behind climate change in a way that is intuitive to broader audiences. The work of the best climate fiction writers, including Long Now Speakers like Robinson and Neal Stephenson, grasps that the paths in and out of climate catastrophe are equally complex. In Stephenson’s most recent novel Termination Shock (02021), a geo-engineering project to inject sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere introduced in the book’s first sections seems at first like a silver bullet solution to warming temperatures. The rest of the book, of course, goes into the much messier geopolitical and social ramifications of the technological solution.

To be sure, a novel — even one as fastidiously researched as The Ministry for the Future or Termination Shock — can’t possibly represent the complex dynamics of climate change as rigorously as a computational model. But perhaps the rigor isn’t the point. Instead, the coherent-enough worldbuilding of a good cli-fi novel can serve as a springboard for thinking seriously about future paths heretofore untracked — to “think the unthinkable,” as the writer Chiara De Leon put it in a piece in Noema in February of this year. Just as institutions like the French and Canadian armies have called upon science fiction writers to help them plan out seemingly unlikely scenarios, so could climate authorities use the dreams of cli-fi authors to help direct their plans for the future.

It’s not so outlandish of a concept. In a March 02022 Long Now Talk, Kim Stanley Robinson noted the “category error” that occurs when people contact him, an English major and science fiction writer, for insight into climate futures. While Robinson judged his increasing prominence as a climate expert as a sign that “we’re in terrible trouble,” there’s an argument to be made that we can best address climate change with the help of more thinkers like him rather than fewer. The more climate futures we imagine, the more ready we are for whatever comes next.

“You need to have diversity in order for selection to work”

Climate fiction can’t achieve its full potential as a tool for imagining the future, however, if it remains dominated by a limited set of perspectives. Both Stephens and Jones noted that even as people of color from the Global South are most impacted by climate change currently, their stories are not yet represented within the most popular works of climate fiction. This discrepancy can be explained in part by pre-existing biases within the publishing industry, which has traditionally limited the opportunities afforded to non-white and non-male writers, as well as similar biases within the environmental movement. Regardless of the cause, leaving out stories that originate in frontline communities of color from the climate fiction picture doesn’t only misrepresent the realities of climate change in the present — it unnecessarily restricts the genre’s ability to imagine the future.

From Jones’ perspective, failing to include stories by authors of diverse backgrounds in the broader conversation around climate fiction will hamper efforts to devise climate adaptation strategies. To him, it’s a matter of basic evolutionary principles: “you need to have diversity in order for selection to work.” The perspectives of climate fiction writers like Amitav Ghosh, whose Gun Island (02019) weaves in Bengali folklore to create a magical realist cli-fi story, or Nnedi Okorafor, whose Who Fears Death (02010) vividly renders an Africanfuturist vision of a desertified sub-Saharan expanse, aren’t just compelling as literary lenses; they offer radically different conceptions of the future from those presented in The Overstory or The Ministry for the Future.

The work of indigenous writers offers a particularly insightful view into climate futures, fueled by the long legacies of ecosystem disruption and colonialism that indigenous peoples the world over have had to withstand. The Waanyi author Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book (02013), for example, places the ramifications of climate change in the context of the broader dispossession of indigenous Australians. Early in the novel, a group of indigenous characters discusses a white climate refugee, noting that “even though she was a white lady, they were luckier than her. They had a home [...] had somewhere, whereas everywhere else, probably millions of white people were drifting among the other countless stateless millions.” Wright’s viewpoint in The Swan Book can often seem nihilistic — a charismatic indigenous politician who is depicted as “leading the development of new laws for the world on the protection of the Earth and its peoples, after centuries of destruction on the planet” is also the novel’s antagonist — but its portrayal of indigenous Australian society surviving even through the worst effects of climate change reveals a perspective of resilience and embattled hope.

It’s a perspective that finds parallels in the work of indigenous environmental scholars like Professor Kyle Whyte, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a Professor of Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan. Pushing back at non-indigenous works within the environmental literature that characterize the shock of climate change as one of impending and final doom for indigenous people, Whyte characterizes indigenous people as “already having endured one or many more apocalypses.” Grace Dillon, who coined the term “Indigenous Futurism” to describe science fiction works that incorporate traditional Indigenous knowledge, similarly notes the focus within many of those works on “persistence, adaptation, and flourishing in the future, in sometimes subtle but always important contrast to mere survival.”

Dillon’s observation on indigenous flourishing was echoed in one of Tory Stephens’ observations on why Imagine 2200 — and climate fiction more broadly — needed to capture the full diversity of those who will be affected by climate change: “different cultures think about hope in different ways.” Without incorporating these different perspectives on hope into our discourses on climate change, we can’t expect to imagine a climate future that ensures justice for all.

Explore Further:

- Watch Jamie Jones' Long Now Talk on climate fiction.

- Watch Neal Stephenson's and Kim Stanley Robinson's Long Now Talks on their climate fiction novels.

- Watch Annalee Newitz' Long Now Talk on why Science Needs Fiction

- Read all the stories in Imagine 2200: Climate Fiction for Future Ancestors, the first climate-fiction contest from Fix, Grist’s solutions lab. Imagine 2200 asked writers to imagine the next 180 years of equitable climate progress.

- Explore the books mentioned in this article: