Becoming “Children of a Modest Star”

Long Now talks with Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman, authors of “Children of a Modest Star,” about pandemics, climate change, and the planetary systems required to deal with them.

LEARN MORE

The point of Children of a Modest Star, the new book by Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman of the Berggruen Institute, is simple: planetary crises require planetary solutions. But what does it mean to think about our problems — and the structures we make to solve them — using what Blake and Gilman refer to as “Planetary Thinking”?

Children of a Modest Star is an ambitious book. In just a few hundred pages, it aims to both outline the current state of global affairs and propose a quietly radical planetary transformation of the hierarchies of governance. Blake and Gilman de-emphasize the national (and even international) systems that can often seem like permanent fixtures and instead point a spotlight on the power that internetworked local and planetary structures could wield against problems like pandemics and climate change.

To get a fuller understanding of Children of a Modest Star, we spoke to Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman about the book, going deeper into its themes of planetary sapience, multiscalar governance, and the temporal reconsideration that planetary thinking requires.

L: Nils GIlman; C: the cover for Children of a Modest Star; R: Jonathan Blake

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Long Now: For those who haven’t had a chance to read the book yet, I think it’d be useful to get an overall gloss on the arc of its argument and especially what you mean when you talk about this concept of planetary thinking.

Jonathan Blake: I can give an overview of the book that takes on that specific question as well, because the first half of the book deals with the questions: What is planetary thinking? How did it come about? What is it in contrast to?

The challenge is that we look around the world and we find ourselves in a situation that’s both dangerous and debilitated. We have a series of very powerful political institutions that are established around the nation-state and divide up the world into neatly packaged bordered territories with central governments in control of what happens within their borders, but have no authority outside of those borders. At the same time, we have lots of different issues, problems, phenomena that, by their very nature, don’t care about those borders that just flow and span and transgress.

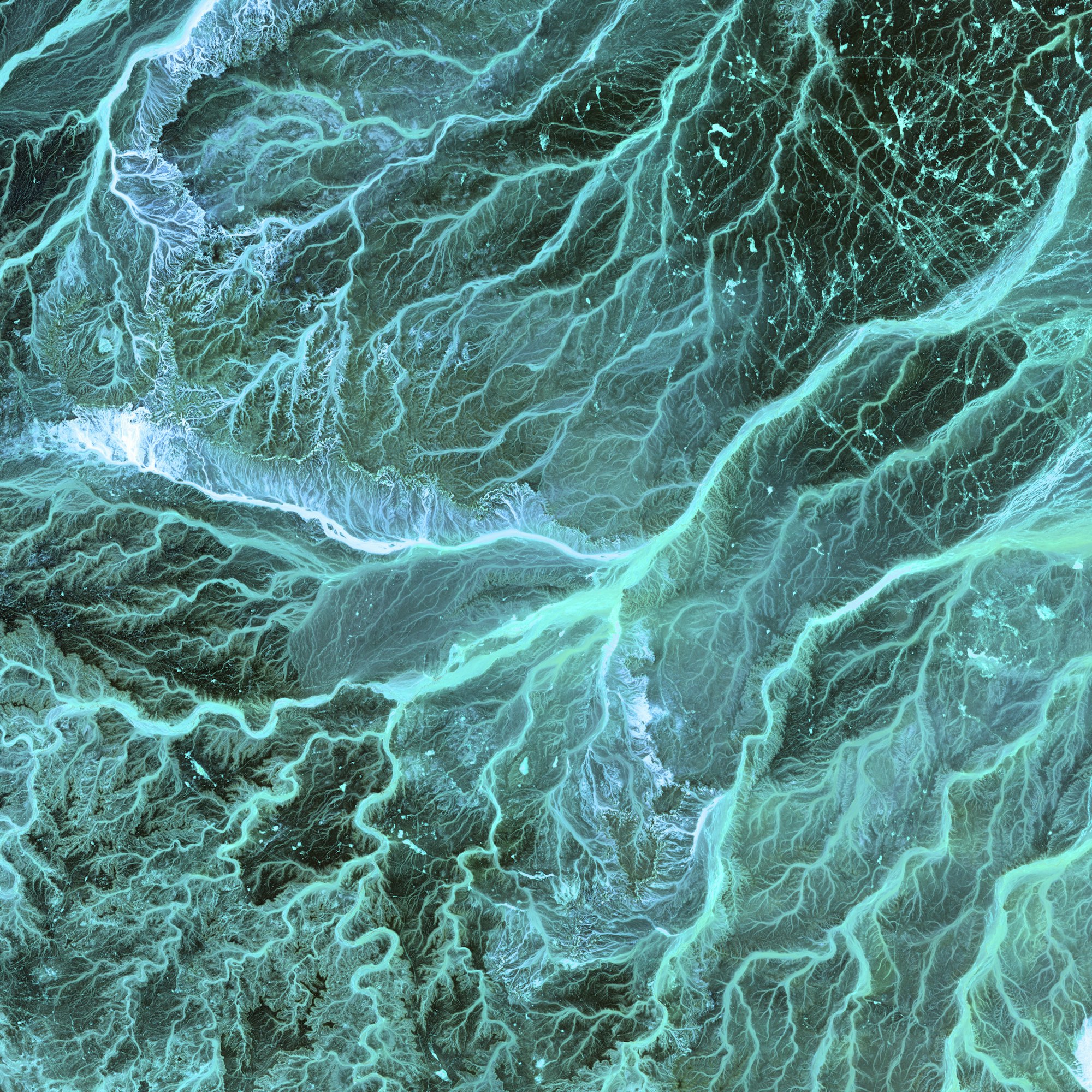

Many of these are what we might call natural systems and they all emerge from the fact that we live on a planet that has had its own cycles and processes going on for billions of years: the carbon cycle, the nitrogen cycle, the flows of biodiversity for plants, animals, even viruses moving back and forth. So our diagnosis is that we’re stuck in this situation where the institutions nominally designed to handle problems that we humans encounter are structurally unable to tackle the problems that we face: our climate change and pandemics, for example.

Planetary thinking is our way to try to move this problem forward. It’s no longer sufficient to think in terms of the national — to think that the nation-state can solve these problems.

The framework of the global is that of a collaboration of national governments. Global institutions are institutions that bring together all the different nation-states to cooperate, but ultimately are responsive not to the problems themselves, but to the nation-states they’re made up of. The canonical case here might be the UNFCCC, which is designed to tackle climate change. Every year it gathers in COPS, which are made up of representatives of the nation-states, and they are unable to achieve meaningful progress at the speed that we need because ultimately it’s the nation-states that are making these decisions. This is a problem that others have identified as well. We’re not fully original there, but we’re saying: “How might we think about this differently?”

We suggest the concept of the planetary as opposed to the national or the global is the one that might move us forward. The planetary recognizes that we are embedded in these systems, these cycles. We’re only one species among many that share the planet. The second half of the book says, “Okay, well this is all well and good, but what do we do about it?”

We propose a whole new way of thinking about how we might govern the planet from top to bottom, fully revamping institutions, creating new institutions that are more attuned and designed to deal with these, what we’re calling planetary phenomena, and would break away from the problems that are just endemic in today’s system.

Nils Gilman: What makes the planetary distinct from the global is that the global, as described by the term globalization, refers to the flows of human-centered things: money, ideas, goods, services, and also bad things: human trafficking, drugs, armaments and so on. Planetary phenomena are all the other things that flow around the planet that don’t care at all about humans and are not based on human conventions or institutions. Human activity may be perturbing these systems, though. We see emergent diseases because humans are encroaching on wildlife, increasing the flow of zoonotic viruses out of natural reservoirs into human populations. Or we see climate change, obviously, being driven by the burning of fossil fuels.

That’s accelerating all sorts of systems and we need to figure out a way to live harmoniously with all of them. Human beings have lived through what amounts to an outbreak over the last few centuries as a result of industrial modernity. The human population today is an order of magnitude larger than it was 300 years ago. The impacts we’re having on the Earth are several orders of magnitude bigger because those 10-times-as-many people are themselves each consuming on average 10 times as much stuff. The amount of consumption and disruption that humans are adding — the anthropogenic forcings, to use the language — is quite remarkable. We’re stuck with a governance system which was conceived several centuries ago and was implemented basically in the middle of the 20th century after World War II to deal with human issues. But we now are disrupting these planetary things and we need a new way to think about it. So the architecture of planetary governance that we propose is one that is adequate to dealing with these challenges.

That’s very clarifying. A lot of the first chapter of the book focuses on this particular historical moment of the hegemonic nation-state. In the book’s conclusion, you write that “sovereignty has been transformed and relocated many times throughout history.” It’s an interesting rhetorical move. What felt important about making the case that the nation-state is not an immutable truth of the world and that it didn’t really become the law of the world until the forties or fifties or sixties?

Gilman: There’s a couple of things at stake with that. One thing that’s very pertinent for the Long Now community is that people tend to think that the structures we have now, especially if they’ve been around for a couple of generations, are permanent fixtures and that they have to be that way. Of course, path dependency is a real thing. You can’t just get rid of systems wholesale without severe disruptions.

If we want to imagine the long-term future of humans on this planet, then we need to get away from the idea that the structures we have now are immutable constraints on those possibilities, right?

That being said, denaturalizing this idea that the present structures we have are ahistorical and permanent is a really important move for being able to imagine different kinds of futures. If we want to imagine the long-term future of humans on this planet, then we need to get away from the idea that the structures we have now are immutable constraints on those possibilities, right?

It opens up the possibility space. So, it’s important to do the work of historicizing and showing that the idea that something that has been around forever is actually a mythology — a retcon. To show that, actually, these systems came into place much more recently. Something that people don’t realize is that if you go back to the end of World War II, almost half the people in the world did not live in nation-states. They lived in empires, they lived in mandates, they lived in all sorts of different kinds of sovereignty arrangements. It was only really in the postcolonial moment, after a lot of different kinds of experiments, that we ended up with the idea that everybody should live in a sovereign national state.

If we realize how recently that came into being as a standard, and we realize the very particular reasons it came to be that standard in the world as it existed in the 01950s and sixties and that are no longer relevant to the world we find ourselves in now, it opens up the possibility to imagine futures that are radically different from our present.

Blake: The work of this part of the book is building on really excellent research that’s been done by historians in the last couple of years, which shows that even at these moments when the nation was expanding its hegemony around the world, lots of people were experimenting with other models — and these were not fringe figures. A lot of the people who are today seen as the founding fathers of the postcolonial nation-state, people like Nkrumah or Nehru were actually in favor of alternative arrangements. They preferred not to have nation-states. In the end, the nation-state was their second choice. These are major political actors who were making critical decisions.

The most striking piece of evidence that you muster in the book on this is that there was a Gallup poll in 01946 where 54% of Americans surveyed said, “Yes, we should make the un into a world government with a military.” That’s something that seems, frankly, bizarre to many modern readers given recent discourse about globalization.

Gilman: I mean, I think one other thing we should emphasize is that Jonathan and I are not saying that we should get rid of nation-states. Nation-states still have really important functions — especially in managing economies and distributional outcomes within economies. The nation-state becomes the hegemonic form of governance in the second half of the 20th century because the central governance project of that period was economic development, both in rich countries and in poor countries. There, the idea was that governments should manage economies to create economic growth and to develop modern infrastructure — technology, governing institutions, and so on. Nation-states are going to continue to have that function — that’s going to continue to be important.

But they weren’t designed to deal with these kinds of planetary issues, which at the time were considered just kind of background noise. At the time the planet was considered the stable stage on which the human drama played out. If you read Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition, which she published in 01958, she’s very explicit about this, that the fungibility of the human condition is predicated on the stability of the planetary condition. What we have learned in the 65 years since her book was published is that those planetary conditions are no longer stable. The stage itself is beginning to rattle and shake, and we need to figure out a way to restabilize that stage.

That’s going to require totally new modes of cooperation and coordination; ones that we can’t even necessarily imagine that easily today. Something that the Long Now community has a lot to contribute to is imagining radically new forms of governance: modalities that go beyond national government as we traditionally have understood it. There still will be roles for national government the same way that when national governments formed, you still needed municipal governments. I don’t think national governments will or should go away, but we do need to get rid of the idea of absolute sovereign independence of nations that get to make absolute decisions about their territorial space, irrespective of the secondary effects those decisions will have on planetary systems that affect us all.

Blake: A very Long Now point here is that we think the nation-state has been here forever, but, in fact, it’s cities that have been around forever. People have been living in Jericho for several thousand years, and the sovereign that’s been over it has changed innumerable times. New York City and Boston are both older than the United States. So when we look at this map and we see the United States, France, and Senegal. Another way to look at that map is to say, here’s Boston, Paris, and Dakar. That’s a different history and a different way of thinking about governance.

In the book you do pan out into the planetary, but there’s so much that emerges from this question of “What if the nation-state is not the conduit through which we do all governance?” that would also revitalize the local, on municipal or regional levels. The contrast that you draw between multilevel and multiscalar forms of governance is useful for understanding the solutions to these

planetary issues.

Gilman: We have a whole chapter in the book that deals with this, where we promote the idea that there should be networked trans-local governance systems. Some of these are already being developed — this is not science fiction. To give an example: if you think about climate change, there are two dimensions to the policy challenge. One is mitigation — trying to prevent more carbon from going into the atmosphere that will heat up the planet and acidify the oceans. That’s got to be dealt with at a planetary scale because when we emit tailpipe emissions here in Los Angeles, it affects the planetary climate everywhere. It affects it in China, it affects it in Africa.

The other is adaptation, and that’s very different. For example, Jonathan and I live in Southern California. The big adaptational challenges of climate change for us here in California are heat waves, fires and droughts. But on the other corner of the country that we live in, the United States, you have Miami. Miami is also facing climate change issues, but it’s facing very different issues. For them it’s sea level rise, it’s hurricanes, it’s storms. One of the things we propose is that a city like Los Angeles or the state of California has more in common in terms of its adaptation challenges with places like Perth, Australia or Spain and Portugal or Cape Town in South Africa than with Miami. By contrast, Miami has more in common with places that are also in low lying areas that are subject to hurricanes. They might have more in common with, say, Ho Chi Minh City or Manila or Dhaka or perhaps in Jakarta. In both cases it makes more sense for cities to network amongst their peers in order to figure out how to use best practices, expertise, and technology that can deal with their challenges. It’s not that the nation-state’s not important, but that there’s these other layers that have opportunities about how we can govern in a more effective way.

Blake: I liked the way that you summarized our argument, which was: What if the nation-state wasn’t the main conduit for governance? So this is precisely it: if something were to happen today in either L.A. or Miami, the first phone call the mayor would make is to Washington D.C.. But in a new, planetary system? You can imagine the first phone call you make is to this new trans-local structure; a trans-local institution that brings together all of the cities that are facing drought and fire with a secretariat somewhere that can bring together all the other relevant mayors who’ve dealt with exactly this thing and know what the protocol is. That’s a different way of tackling these issues, a different way of thinking about governance, a way to denaturalize certain ideas and show other possibilities. It’s not to say that that phone call to Washington would never happen, but maybe it’s not the first one.

So much of the book and much of what we’ve talked about has focused on this shift on physical scales, whether out into the planetary or down into the local and then across into the trans-local. But Nils, you also brought up to me this idea of the temporality of the planetary. And I think that’s shown in the book because you focus on pandemics and climate change, which are two things that are absolutely planetary crises and work on completely different temporal scales than the human ones we commonly reckon with. So, how does that temporal perspective shape the questions of governance that this book grapples with? Because humans are still the ones doing the bulk of the governing even in this planetary future, right?

Gilman: Humans are still doing the bulk of the governing, no doubt. One of the things, though, that we bring up in the book is that we’ll need to incorporate non-human perspectives on temporality into the way we think about governance. There are emerging technological affordances, particularly around ai, that are amplifying our ability to listen to non-human others. For example, there are sensor networks that are being deployed throughout the Sierra Nevada that are tracking the stress levels of the forest by detecting the pheromones of forest life — plants and insects, mostly — because certain pheromone signatures indicate the risks of ecological collapse at a site. Scientists are able to actively listen to plants and animals expressing, in a sense, their experience of climate change and ecological disruption.

So there are possibilities to listen. When we think about governance, it’s often in terms of the people voting, but the people don’t just vote. They also express themselves in various ways in terms of writing op-eds and showing up at town halls and so on. We can imagine incorporating the voices of non-human others who have very different kinds of temporal scales. We look at forests in California, and we know something about historical burn patterns. We know about those burn cycles because we’ve been able to look at the tree rings of very old trees. These trees are essentially giving us a long-term reading of how the climate has changed over time and how they’ve responded to various disruptions that have happened to them over time, unfolding over thousands of years.

At a much shorter timescale, bacteria reproduce in as fast as 10 minutes, and so they’re responding much more quickly to environmental changes than humans can really even imagine. Similarly, insects are always the first to respond in any kind of environmental crisis. The work of the ecologist Camille Parmesan has been tracking the movement of butterfly ranges up through the Rockies as a result of global warming. You see the shifts in populations of many animals and plants. These are all signals that we can potentially harvest that are much more sensitive to temporal scales outside of the terms of human timescales — in terms of our lifetimes and our parents and our children’s lifetimes.

What would it mean to think about governance on the scale of the bristlecone pine or the giant sequoia?

Blake: Another way to think about this is politics. Human politics take place on the scale of elections every two or four years. When we want to think long-term, you can think in terms of a lifespan — we live between 50 and 80 years. Often the longest term people think about is the sake of their grandchildren. That’s obviously good — better than thinking of a two-year election cycle, at least for some things. But what would it mean to think about governance on the scale of the bristlecone pine or the giant sequoia? That doesn’t mean that humans should suddenly start living as if they’re bristlecone pines, but it does mean there are other ways we can be thinking about this — other factors that we want to think about. The same thing happens to do with various biogeochemical cycles, which happen without our knowing and entirely support our ability to live on this planet. What does it mean to take seriously that we’re embedded in the phosphorus cycle, the nitrogen cycle, each with their own temporalities?

It is a huge challenge because we’re only human and we’re living in bodies that have a certain sense of rhythm and time. One of the challenges is dealing with this vastness of the planetary — a vastness not just of geographic scale but also a temporal scale that’s hard to wrap our heads around. To go back to the distinction between the global and the planetary: one of the major distinguishing features between the two is this question of temporal scale. The global is less concerned with the vastness of time that is central to our conception of the planet. If we’re going to take seriously what it means to be embedded in the long history of life, it means thinking for a minute about the fact that the oxygen we’re breathing has to do with the work of cyanobacteria that began billions of years ago. So that long time-scale is just another factor that we think needs to be taken very seriously as we’re making decisions and designing institutions.

You bring up late in the book around the concept of planetary sapience that we also have to have this commitment to epistemic humility. We have to recognize that we don't know everything now and that there are many things that we may never be able to know about the planet. You write of the “hubristic belief at the heart of modernity that everything is knowable,” which is a really striking concept. Yet this is, of course, a very deeply researched book, and you cite many scientists who are trying to make things knowable. In the acknowledgements you thank the late Karen Bakker, whose work on Bioacoustics is very much resonant with what you talked about in terms of trying to hear what the rest of the planet is trying to tell us. So, considering the sheer mass of data that is gained once we take this planetary perspective: how do you practically grapple with that vast amount of information?

Blake: One way we think about planet sapience is that it is technologically enabled. The human mind is limited, so the only way we know the planetary – that we're aware of these things that we've been talking about – is because of technologies, both of sensing and of computation and analysis. So I don't think we're techno-utopians, but we're techno-reliant. There's an important role for technology here, and it's certainly part of our vision: these are tools that we have and we'd be foolish to set them aside. We absolutely need to guide them to ensure they're working for us in the best way that we can. But going forward, we're going to need to rely on technology. Our colleague, Benjamin Bratton, once wrote that climate change is anthropogenic and so the solutions to it will just have to also be anthropogenic.

We kind of created this mess through our technologies. We're going to have to rely on these technologies to help us out of it. I know that can be a loaded statement. I'm not suggesting any particular technologies, only that they're going to have to be part of the solution. One way to think about it can be found in Karen Bakker’s forthcoming book Gaia's Web, which I highly recommend to your community as a way to think about the very practical ways that today's technologies could be used for the governance of environmental and ecological issues. We’re building on her work and thinking at an even larger scale and further into the future. But for a lot of cutting edge, present day thinking, her work is phenomenal.

Gilman: I would add that another key influence on our thinking is Stewart Brand and his Whole Earth Discipline book, the subtitle of which was “an eco-pragmatist manifesto.” Stewart manifests in that book and throughout his career an understanding that you don't want to be a techno-utopian, but you do want to be a techno-optimist, and you want to don't think that technology is going to solve every problem in the world, but there's very few major problems in the world that aren't going to need some technological innovation in order for us to make significant headway against them.

Our epistemic humility is rooted in a basic understanding of what the scientific method is all about. Every finding in science is provisional. It's a hypothesis about the way the world is, subject to testing and revision based on more data or new theories about the world. However, at the same time, we need to act in the world. The most fundamental philosophical question is what should I do? Passivity in the face of the planetary disruptions that we're facing today is not an option. We have to do things now. We should be careful – we shouldn't take crazy risks – but we have to try to do the best we can based on the knowledge we have, and always be prepared to revise based on new knowledge.

Every finding in science is provisional. It's a hypothesis about the way the world is, subject to testing and revision based on more data or new theories about the world. At the same time, we need to act in the world.

One of the things that I think went disastrously wrong worldwide, but especially in the United States during the pandemic, is that when the COVID-19 virus first emerged in China there was a lot of scientific uncertainty about the virus and how it was transmitted. Remember, we all thought it was mainly about washing our hands and wearing gloves and washing our groceries in the first months. Then we realized it's primarily airborne and that masking is more important. When mask mandates came in, there were people who said, “What the hell? We thought it was a glove mandate, and now you're telling us it's a mask mandate.”

So I think people who were not very well versed with the scientific method became increasingly skeptical. That was an example of a disjuncture between the cognitive temporalities of science and the cognitive temporalities of political decision making. Politicians were in charge of making decisions: Should we shut the schools or not? Should we mandate masks or not? These were choices that had to be made, but the science at that particular moment was uncertain. And then as science advances, it may turn out that some of the decisions that were made earlier were based on science that would later be revised. That doesn't mean that those decisions were wrong. That just means that those decisions needed to be revised.

This is perhaps jumping the gun on the order of centuries, but: Tied into this epistemic humility and this awareness of how the scientific method works – and also how structures like sovereignty have always been mutable, never sticking in one way — do the two of you have a vision for what may come after the planetary frame of governance?

Gilman: My first answer is that if this book is successful, our hope is that 10 years from now, people will talk about planetary challenges with the same facility as people talked about global challenges in the 01990s and 02000s. I don't think there's any final stage of history. I'm not a Hegelian who thinks that we're going to solve all the philosophical problems once and for all and come up with some governance structure that solves every issue. Humans are a fractious lot, and we will always have challenges. But we can imagine various futures where there are very different kinds of networks of people, and not just people, but what we today call machines and others that are collaborating in ways that are currently almost unimaginable.

One person who gave me a lot of thought about this a few years ago is actually Kevin Kelly, who talked about the future of AI with this very striking metaphor. He said the future of AI will be like a giant menagerie of many different kinds of AIs with many different kinds of intelligences. I like that analogy because we talk about the modernist, Cartesian triangle of humans, machines and animals. Kevin's analogy breaks down the barriers between the machines and the animals and says that just as there are many kinds of animal intelligence, there'll be many kinds of machine intelligence. In fact, there'll be many kinds of machine intelligences that are interacting not just with human intelligences, but with non-human intelligences and forms of cognition. And so the ways in which all of these things will come together into creating fully new kinds of consciousnesses, I think is actually an inevitable future. And what exactly that's going to look like in terms of how it plays out in terms of governance, I think that's really pretty unimaginable right now. But I do think that that kind of emerging cognitive infrastructure is already happening right now in what John referred to earlier as planetary sapiens.

Blake: I'm interested in various futures along the lines of planetary identity or forms of planetary identifications. The less hopeful one is the Independence Day scenario, where you come to identify with and act as a planet because of an attack from outside the planet. Instead, I think that looking at the histories of identification, you see two things. First is that all have many identities. I have a professional identity, personal identity, ethnic, national, political. There could be another category that most of us don't think about yet: a planetary identity that is complimentary with all these other ones. Second is that the history of political identity shows that these things change over time. Right now we think in terms of the nation-state, because that's the powerful, dominant institution. This, of course, is a modern construct as Benedict Anderson and many others have shown. Before, we identified primarily with religions or with very local identities based on city or region. So they shift across time, across scale, depending on what's pertinent to the technologies that are available to us. Our vision emphasizes not the nation-state, which is kind of the meso level, but instead the local level and on the other hand, the planetary level, there are all sorts of new confrontations of identity that could emerge.

I'm not speculating on what they might be, just that they will be. I'm curious to see what will form out of them and hope, of course, that identification at that level of one planet allows for forms of cooperation and peace that are made difficult by national and ethnic and identification.

So, to end on a hopeful note: maybe this new scientific emergent reality and how we're now coming to understand ourselves as embedded in the planet opens up new ways of thinking about ourselves and our politics that are nourishing for us all.

Children of a Modest Star is out now from Stanford University Press.

Join our newsletter for the latest in long-term thinking

Subscribe